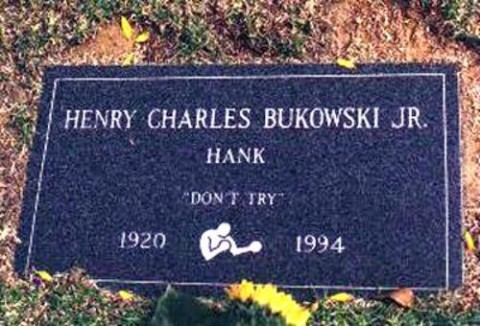

In 1994, Charles Bukowski was buried in a Los Angeles cemetery, beneath a simple gravestone. The stone memorializes the poet’s name. It recites his dates of birth and death, but adds the symbol of a boxer between the two, suggesting his life was a struggle. And it adds the very succinct epitaph, “Don’t Try.”

In 1994, Charles Bukowski was buried in a Los Angeles cemetery, beneath a simple gravestone. The stone memorializes the poet’s name. It recites his dates of birth and death, but adds the symbol of a boxer between the two, suggesting his life was a struggle. And it adds the very succinct epitaph, “Don’t Try.”

There you have it, Bukowski’s philosophy on art and life boiled down to two words. But what do they mean? Let’s look back at the epistolary record and find out.

In October 1963, Bukowski recounted in a letter to John William Corrington how someone once asked him, “What do you do? How do you write, create?” To which, he replied: “You don’t try. That’s very important: ‘not’ to try, either for Cadillacs, creation or immortality. You wait, and if nothing happens, you wait some more. It’s like a bug high on the wall. You wait for it to come to you. When it gets close enough you reach out, slap out and kill it. Or if you like its looks you make a pet out of it.”

So, the key to life and art, it’s all about persistence? Patience? Timing? Waiting for your moment? Yes, but not just that.

Jumping forward to 1990, Bukowski sent a letter to his friend William Packard and reminded him: “We work too hard. We try too hard. Don’t try. Don’t work. It’s there. It’s been looking right at us, aching to kick out of the closed womb. There’s been too much direction. It’s all free, we needn’t be told. Classes? Classes are for asses. Writing a poem is as easy as beating your meat or drinking a bottle of beer.”

The key to living a good life, to creating great art — it’s also about not over-thinking things, or muscling our way through. It’s about letting our talents appear, almost jedi-style. Or is it?

In 2005, Mike Watt (bass player for the Minutemen, fIREHOSE, and the Stooges) interviewed Linda Bukowski, the poet’s wife, and asked her to set the record straight. Here’s their exchange.

Watt: What’s the story: “Don’t Try”? Is it from that piece he wrote?

Linda: See those big volumes of books? They’re called Who’s Who In America. It’s everybody, artists, scientists, whatever. So he was in there and they asked him to do a little thing about the books he’s written and duh, duh, duh, duh, duh. At the very end they say, is there anything you wanna say, you know, what is your philosophy of life, and some people would write a huge long thing. A dissertation, and some people would just go on and on. And Hank just put, “Don’t Try.” Now, for you, what do you think that means?

Watt: Well for me it always meant like be natural.

Linda: Yeah, yeah.

Watt: Not like…being lazy!

Linda: Yeah, I get so many different ideas from people that don’t understand what that means. Well, “Don’t Try? Just be a slacker? lay back?” And I’m no! Don’t try, do. Because if you’re spending your time trying something, you’re not doing it…“DON’T TRY.”

It’s Monday. Get out there. Just do it. But patiently. And don’t break a sweat.

Related Content:

Charles Bukowski: Depression and Three Days in Bed Can Restore Your Creative Juices (NSFW)

Tom Waits Reads Charles Bukowski

The Last Faxed Poem of Charles Bukowski

Listen to Clips of Bukowski Reading His Poems in our Free Audio Books collection.