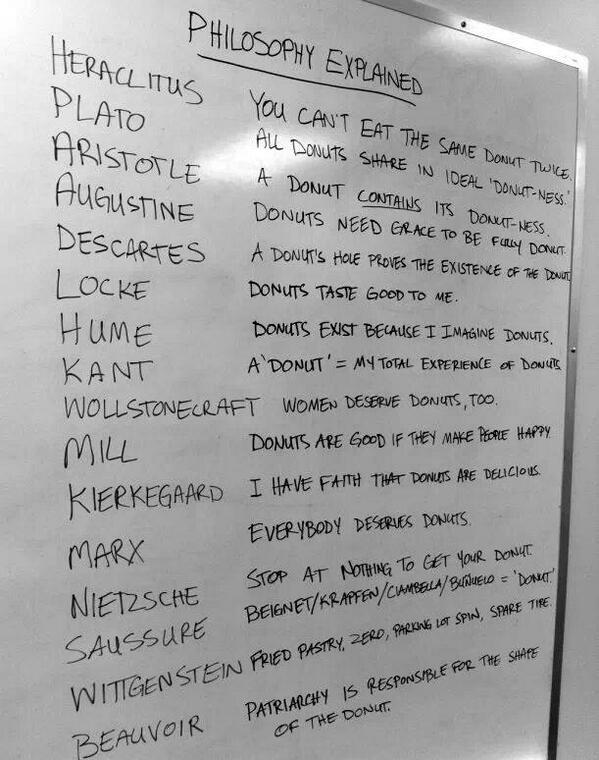

We’ve all seen them, on the boardwalks of Venice Beach or of the Jersey Shore: poop-joke t‑shirts that state the gist of various world religions or philosophies by reference to the aforementioned bodily function. Clever they aren’t, but the form adapts to another, more tasteful formulation (pun most definitely intended) in the list above, which briefly describes the philosophical programs of sixteen prominent Western thinkers with reference to that universally beloved food, the donut. To wit: pre-Socratic Greek philosopher Heraclitus gets summed up with “You can’t eat the same donut twice,” a twist on one of his famous few aphorisms. Ludwig Wittgenstein’s philosophy becomes an elliptical series of possible donuts in various language games: “Fried Pastry, Zero, Parking lot spin, Spare tire.” And so on.

No need to point out the oversimplification inherent in this strategy; that’s kind of the point. It’s a joke, after all, but one the author—whoever that is—clearly intends as a means of breaking the ice and getting down to more serious explorations. But what if the donut is the serious exploration? Such is the case in a 2001 article published in the journal Basic Objects: Case Studies in Theoretical Primitives by Columbia philosophy professor Achille C. Varzi.

Simply titled (in the British spelling) “Doughnuts,” Varzi’s paper explores the donut, or “torus” in the language of topographers, as a theoretical object for an ontological thought experiment. In short, he asks whether or not we can say that the donut hole is an actual existing entity or simply a figure of speech, a “façon de parler.” In the traditional view, that of the topographers, who practice “a sort of rubbery geometry…. The only thing that matters is the edible stuff. The hole is a mere façon de parler.”

On another, more three-dimensional view of the relationship “between void and matter,” things look different: “We must be very serious about treating them [donut holes] as fully-fledged entities, on a par with the material objects that surround them.” The real existence of the hole cannot be easily dismissed without running into a problem, “the dilemma of every eliminative strategy: if successful, it ends up eliminating everything just in order to eliminate nothings.” No hole, no donut. (Though, as Simone De Beauvoir apparently recognized, “Patriarchy is responsible for the shape of the donut.”) The donut hole thesis also forms part of the argument in an academic philosophy paper from 2012 entitled “Being Positive About Negative Facts” from Philosophy & Phenomenological Research. On the way to showing that “negative facts exist in the usual sense of existence,” authors Stephen Barker and Mark Jago, both of the University of Nottingham, come to similar conclusions about the donut, with reference to earlier work by Varzi:

Holes pose something of a philosophical quandary and, perhaps as a result of their mystery, are often treated as immaterial entities (Casati and Varzi 1994). Yet we seem to be able to perceive holes, gaps, dents and the like. The view of holes as immaterial objects is, we think, very much in line with thinking of the negative as the metaphysically undead. Given our acceptance of negative facts, we can offer a story about holes on which they are material entities. If there is a donut hole then there is a spatial region involving the instantiation of donut-dough which is intimately connected with an absence thereof.

Make of these claims what you will, but I think what we see in both essays is that serious interest in a frivolous object can produce illuminating discussion. That describes the thesis of the site Improbable Research, who bring us both of these donut examples; their motto—“Research that makes people LAUGH and then THINK.” I don’t know if either essay—or even the donut joke at the top of the page—really makes for ha-ha laughs so much, but these arguments about the material existence of the immaterial space of donut holes certainly challenged my thinking.

Related Contents:

140+ Free Online Philosophy Courses

Philosophy Referee Hand Signals

Monty Python’s Best Philosophy Sketches

The Epistemology of Dr. Seuss & More Philosophy Lessons from Great Children’s Stories

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

“Well it’s 9th and Hennepin

And all the donuts have

Names that sound like prostitutes”

— Tom Waits, 9th and Hennepin

Sign has Locke and Hume reversed. Oops.

Buddha: The hole of the donut is no more empty than the entire donut.

FOUCAULT: we should stop thinking about donuts as good or bad. The key is to practice technologies-of-self that allows us to have a relationship with donuts that is played out with a minimum of domination.

i guess Philosophy Matters after all.

Jesus: Donut others as you would wish yourself donutted.

wordlessly, Linji gives donut to you, takes it away and gets outside of it. then he beats you and walks off. you finally grock the shit.

Homer Simpson: Donuts. Is there anything they can’t do?

Mathematician:

A donut and a coffee mug are the same thing.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Mug_and_Torus_morph.gif

Hamlet: Donut or not donut, that is the question.

I actually think Locke’s should read: “I made the doughnuts, so the doughnuts are mine.”

Only two women, both brilliant philosophers, whose time was caught up with gender politics. Philosophy needs more women.

Hmm. We are talking about borders and boundaries as defining an object. If nations are defined by their borders, so are oceans; why aren’t their inhabitants represented in the councils of nations?

Splash that around a little; let’s see see who gets wet.…

“Life is good, but donuts make it better”

.Homer Simpson

…

They left out the most important one by the singer Crystal Gayle… “Donut make your brown eyes blue”.

Oops… I mean, “Donut make my brown eyes blue”. A pox upon me for getting that wrong. 🤣

That’s the diabetes.