In the United States and the UK, we’ve seen the emergence of a multibillion-dollar brain training industry, premised on the idea that you can improve your memory, attention and powers of reasoning through the right mental exercises. You’ve likely seen software companies and web sites that market games designed to increase your cognitive abilities. And if you’re part of an older demographic, worried about your aging brain, you’ve perhaps been inclined to give those brain training programs a try. Whether these programs can deliver on their promises remains an open question–especially seeing that a 2010 scientific study from Cambridge University and the BBC concluded that there’s “no evidence to support the widely held belief that the regular use of computerised brain trainers improves general cognitive functioning in healthy participants…”

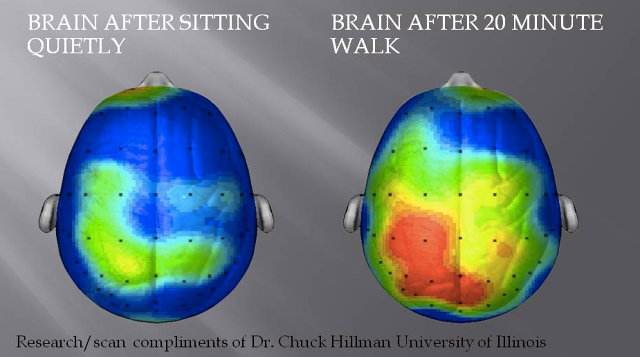

And yet we shouldn’t lose hope. A number of other scientific studies suggest that physical exercise–as opposed to mental exercise–can meaningfully improve our cognitive abilities, from childhood through old age. One study led by Charles Hillman, a professor of kinesiology and community health at the University of Illinois, found that children who regularly exercise, writes The New York Times:

displayed substantial improvements in … executive function. They were better at “attentional inhibition,” which is the ability to block out irrelevant information and concentrate on the task at hand … and had heightened abilities to toggle between cognitive tasks. Tellingly, the children who had attended the most exercise sessions showed the greatest improvements in their cognitive scores.

And, hearteningly, exercise seems to confer benefits on adults too. A study focusing on older adults already experiencing a mild degree of cognitive impairment found that resistance and aerobic training improved their spatial memory and verbal memory. Another study found that weight training can decrease brain shrinkage, a process that occurs naturally with age.

If you’re looking to get the gist of how exercise promotes brain health, it comes down to this:

Exercise triggers the production of a protein called brain-derived neurotrophic factor, or BDNF, which helps support the growth of existing brain cells and the development of new ones.

With age, BDNF levels fall; this decline is one reason brain function deteriorates in the elderly. Certain types of exercise, namely aerobic, are thought to counteract these age-related drops in BDNF and can restore young levels of BDNF in the age brain.

That’s how The Chicago Tribune summarized the findings of a 1995 study conducted by researchers at the University of California-Irvine. You can get more of the nuts and bolts by reading The Tribune’s recent article, The Best Brain Exercise May be Physical. (Also see Can You Get Smarter?)

You’re perhaps left wondering what’s the right dose of exercise for the brain? And guess what, Gretchen Reynolds, the phys ed columnist for The Times’ Well blog, wrote a column on just that this summer. Although the science is still far from conclusive, a new study conducted by The University of Kansas Alzheimer’s Disease Center found that small doses of exercise could lead to cognitive improvements. Writes Reynolds, “the encouraging takeaway from the new study … is that briskly walking for 20 or 25 minutes several times a week — a dose of exercise achievable by almost all of us — may help to keep our brains sharp as the years pass.”

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

This Is Your Brain on Jane Austen: The Neuroscience of Reading Great Literature

New Research Shows How Music Lessons During Childhood Benefit the Brain for a Lifetime

Free Online Psychology & Neuroscience Courses

I am 70 years + 4 month Old ( a Senior )

I am alone, my family (wife, son & daughter ) are in

Karachi, I am on Permanent Resident Card holder

valid till 2022, having no job, want to avail this

Senior living fecility.

nice your project of brain exercise. i like it very much and its very helpful for me and others. your program is totally different exercise program. Thanks to your for your new programs advice.

Whats it all aboot??

Send this message to the deep red states.

☺ :)