Before electronic amplification, instrument makers and musicians had to find newer and better ways to make themselves heard among ensembles and orchestras and above the din of crowds. Many of the acoustic instruments we’re familiar with today—guitars, cellos, violas, etc.—are the result of hundreds of years of experimentation into solving just that problem. These hollow wooden resonance chambers amplify the sound of the strings, but that sound must escape, hence the circular sound hole under the strings of an acoustic guitar and the f‑holes on either side of a violin.

I’ve often wondered about this particular shape and assumed it was simply an affected holdover from the Renaissance. While it’s true f‑holes date from the Renaissance, they are much more than ornamental; their design—whether arrived at by accident or by conscious intent—has had remarkable staying power for very good reason.

As acoustician Nicholas Makris and his colleagues at MIT recently announced in a study published by the Royal Society, a violin’s f‑holes serve as the perfect means of delivering its powerful acoustic sound. F‑holes have “twice the sonic power,” The Economist reports, “of the circular holes of the fithele” (the violin’s 10th century ancestor and origin of the word “fiddle”).

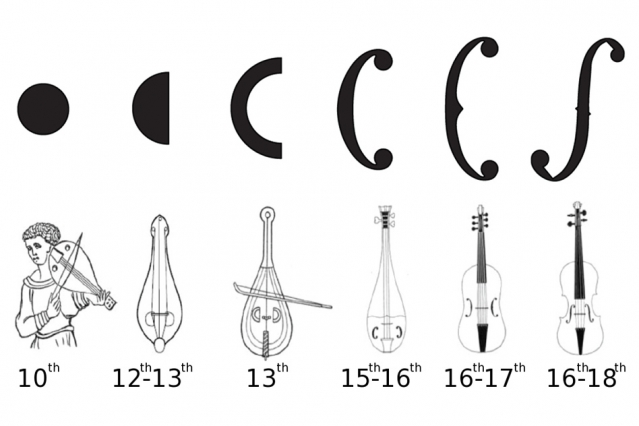

The evolutionary path of this elegant innovation—Clive Thompson at Boing Boing demonstrates with a color-coded chart—takes us from those original round holes, to a half-moon, then to variously-elaborated c‑shapes, and finally to the f‑hole. That slow historical development casts doubt on the theory in the above video, which argues that the 16th-century Amati family of violin makers arrived at the shape by peeling a clementine, perhaps, and placing flat the surface area of the sphere. But it’s an intriguing possibility nonetheless.

Instead, through an “analysis of 470 instruments… made between 1560 and 1750,” Makris, his co-authors, and violin maker Roman Barnas discovered, writes The Economist, that the “change was gradual—and consistent.” As in biology, so in instrument design: the f‑holes arose from “natural mutation,” writes Jennifer Chu at MIT News, “or in this case, craftsmanship error.” Makers inevitably created imperfect copies of other instruments. Once violin makers like the famed Amati, Stradivari, and Guarneri families arrived at the f‑hole, however, they found they had a superior shape, and “they definitely knew what was a better instrument to replicate,” says Makris. Whether or not those master craftsmen understood the mathematical principles of the f‑hole, we cannot say.

What Makris and his team found is a relationship between “the linear proportionality of conductance” and “sound hole perimeter length.” In other words, the more elongated the sound hole, the more sound can escape from the violin. “What’s more,” Chu adds, “an elongated sound hole takes up little space on the violin, while still producing a full sound—a design that the researchers found to be more power-efficient” than previous sound holes. “Only at the very end of the period” between the 16th and the 18th centuries, The Economist writes, “might a deliberate change have been made” to violin design, “as the holes suddenly get longer.” But it appears that at this point, the evolution of the violin had arrived at an “optimal result.” Attempts in the 19th century to “fiddle further with the f‑holes’ designs actually served to make things worse, and did not endure.”

To read the mathematical demonstrations of the f‑hole’s superior “conductance,” see Makris and his co-authors’ published paper here. And to see how a contemporary violin maker cuts the instrument’s f‑holes, see a careful demonstration in the video above, and learn more about the art and science of violin-making here.

Related Content:

Watch a Luthier Birth a Cello in This Hypnotic Documentary

The Art and Science of Violin Making

Why You Can Never Tune a Piano

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Wouldn’t the C shape be easier to break compared to the F?

Indeed, a most curious evolution. The f‑hole, in addition to providing a port for the projection of sound, also allows for a freer vibration and response of the top and bridge assembly. Too “loose” and tone is sacrificed for mere volume with a “flabby” low end. Too “tight” and the instrument feels stifled with a lack of brightness and substantial loss of volume. Of course, all this is balanced against a hundred other variables: top thickness graduation, the setting of the soundpost which communicates vibration to the back, the thickness and graduation of the back, string tension, varnish, wood specific density and stiffness, etc. etc. etc.

Making a violin is a wonderful trip down a bottomless rathole of ideas to try and elusive rewards. As one who builds, I recommend it most highly. :)

“Attempts in the 19th century to ‘fiddle further with the f‑holes’ designs actually served to make things worse, and did not endure.”

I’ve been fond of Savart-style violins for ease of construction, as well as proving themselves just as capable in sound production and projection as more “standard” violins. The Savart violin is trapezoidal, with little soundboard curvature and two long, narrow slots serving as soundholes, rather than f‑holes. Purists will, of course, turn their noses up at such abominations on sight.

I was wondering.

Can “f” holes also work on loudspeakers? For instance, sub woofers which have that lateral “o” shaped hole on the side.

Dear Sirs, the proto describing the shape of f‑holes among the centuries maybe it is not accirate. We have an a fresco dated 1239 in Bassano del Grappa, (VI) Italy, showing a portrait of a court player holding a viella with the f‑holes perfectly designed. I can attach the picture of this once I get a valid email address. thank you

Can you post some photos of the 19th century versions that didn’t help? Thanks!

Also, think of it from a woodworker’s — or, if you will, industrial designer’s — perspective. Holes in a spruce soundboard will leave edges of wood exposed and unsupported. These areas will be vulnerable because if the wood develops tensions over time (i.e. shrinkage), an unsupported edge is the spot where cracks are liable to start off, through the board along the grain. Also, these edges will naturally dry out faster than the rest of the board, causing extra shrinkage around the hole. This is one reason why, in more sophisticated instruments, the edges of round soundholes are usually bound with some sort of purfling or inlay — not just for decoration, but to keep, so to speak, the soundhole ‘together’.

This is also one of the reasons you wouldn’t want your C‑hole — if that is your next choice of shape — to end in sharp corners (supposed elegance being another). It’s a sure bet that, over time, a crack will develop right there. It will be much safer to cut the ending in the shape of a soft curve, especially when it spirally winds back into its own curl. Hence the development of the ‘dots’ on the points of the C‑hole.

Then why change the C‑hole to an f‑shape? Again, risk of damage: the ‘peninsula’ inside the C‑hole will be relatively weak. More importantly, the C‑shape, by ‘surrounding’ the bridge, cuts off a relatively large area of the sound board from transmitting vibration. The first solution to that problem would have been to flip them over (see the sixteenth / seventeenth century instrument in above illustration), but that requires a wider waist. In organising space, especially on the small box that is the violin, the f‑hole — gently following the outer curve of the soundboard — is simply the better solution. (Why a violin would have to be so narrow at the waist is, of course, another question…)

I am game, Ronald. Tell us more about the narrow waist of the violin.

I would think it would be necessary with the fairly low bridge of Baroque instruments in order to allow clean bow access to the strings. What other ideas do you have?

:)

Just like the cutaway on a modern guitar.

Fascinating information.…!!!! Thanks

1,000,000

While it doesn’t change the story much, the idea of a “soundhole” is in itself a misconception. The porting of the body is necessary to keep the air volume in a body from impeding the vibrations of the instrument’s top. The entire top vibrates and creates the air movement that is the sound. The reflected vibrations make a difference, but the sound doesn’t really come from inside the instrument. All of the construction techniques are designed to optimize and control how the top vibrates to give the best tone and volume. The vent size and shape help focus the air resistance inside.

The author Totally missed one of the main things about F‑holes and it has nothing to do with sound coming out, it has to do with the freeing of the vibration of the top, which is driven by the bridge, which sits DIRECTLY BETWEEN the f‑holes.

They provide a more focused area of top vibration which improves volume and expression.

Victor Martin hits the nail on the head… and the perspective from Ronald Veerman was very eye-opening to me.

Really, this research is absolutely woeful.

A Massachusetts Institute of Technology team simply didn’t realise that the violin is not a wind instrument? I thought MIT had a reputation for having some of the best brains in the world.

The sound doesn’t come out of the holes, you fools! The *second* obvious test for looking into how the violin produces sound would have been to close the holes with acoustic damping and see if it silences the instrument. (Spoiler alert; it doesn’t.)

The *first* obvious thing to research would be to see if there were any others who have worked on the same problem before you. A quick skim through “The Violin Explained — components, mechanism and sound” written by Sir James Beament, published by Clarendon Press in 1997 would have been a good start, and then you would”t have wasted all that time and effort coming up with a wildly foolish answer.

A bit late on this post, but worthy I believe… the world-class violin luthier Sam Zygmuntowicz has done an extensive research on how the shape of the violin affects the sound, feeding Stradivarius and Guarneri violins through the MRI machine and using other scientific measurements and 3D simulations, documented and published in his research Strad3D. https://strad3d.org/ He specifically addresses the F‑hole in the research. You can SEE how the sound is produced!

The holes you are probably referring to are called bass reflex, which are meant to control pressure levels inside the closed cabinet, due to the speaker’s own movement. Otherwise, the pressure in the cabinet would exert force on the loudspeaker and change its response.

Otherwise, loudspeakers are driven by amplifiers which take care of the desired volume without having to resort to passive means like soundboxes.

Isn’t it all a bit Eurocentric though? The old fashioned history books make everything look as if it originated in the West and yet there was a time when the East was more advanced in many areas. The Renaissance owed a lot to Arabic cultures and without a doubt used a lot of Arabic instruments. Certainly the flaming sword of Islam sound holes as seen on viola de amores etc. look more like f‑holes. Bowed strings did not start in the west but originated with nomadic horse people (hence the horsehair), by all accounts in Mongolia. I see the modern Morin Khur has f‑holes. Maybe it would be interesting to find and ancient version.

Violin. not and Ehur, not an Oud. Violin. An instrument despite the history of it’s ancestors was built and improved mainly in Europe. Some in England but…Europe.

No-one is disputing the origins of algebra, bows and the rich histories therein.

But they are not talking about it because it has little if any relevance to the ‘Case in Point’.