As the nameless assassin protagonist of Jim Jarmusch’s The Limits of Control makes his way through Spain, he meets several different, similarly mysterious figures, each time at a different café. Each time he orders two espressos — not a double espresso, but two espressos in separate cups. Each time his contact arrives and asks, in Spanish, whether he speaks Spanish, to which he responds that he doesn’t. Each conversation that follows ends with an exchange of matchboxes, and each one the assassin receives contains a slip of paper with a coded message, which he eats after reading, containing directions to his next destination.

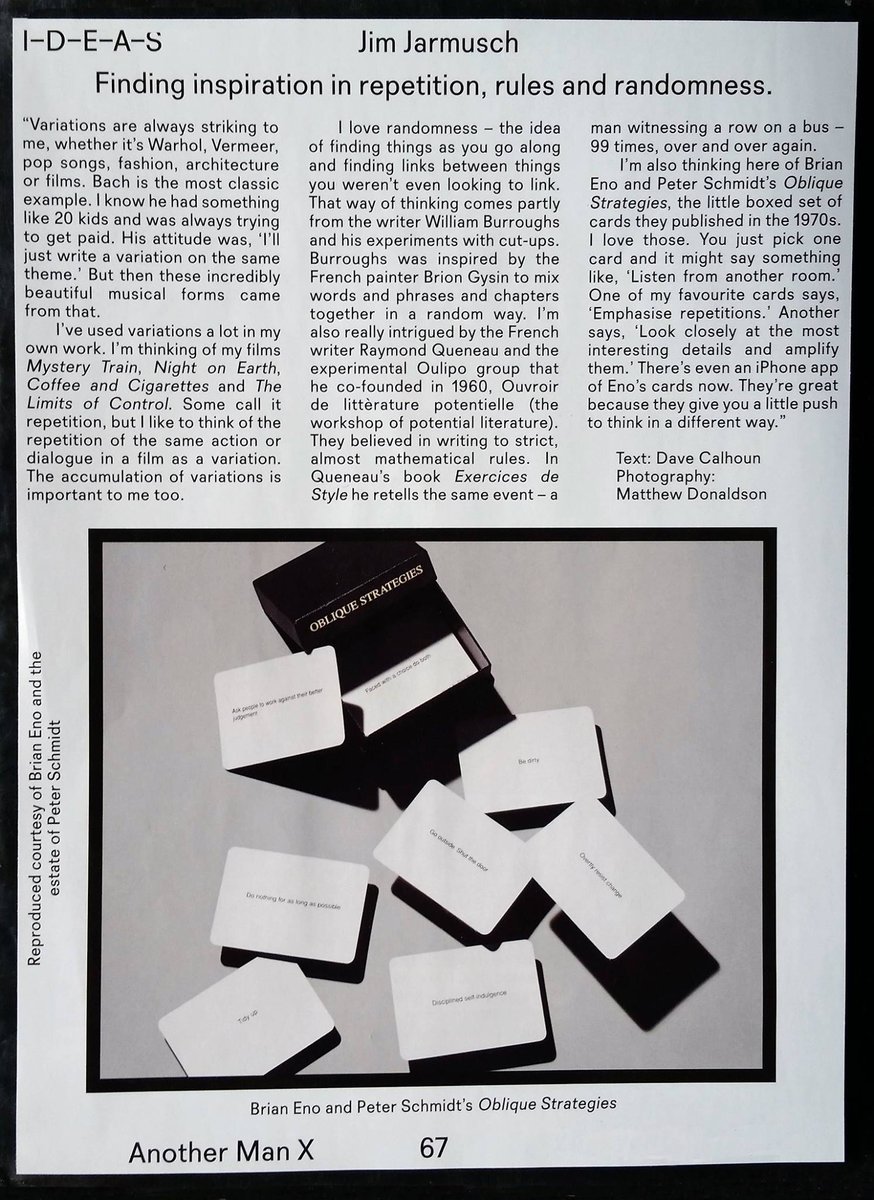

All these elements remain the same while everything else changes, a structure that showcases Jarmusch’s interest in theme and variation as clearly as anything he’s ever made. “Some call it repetition,” he says in the page above from fashion and culture biannual Another Man, “but I like to think of the repetition of the same action or dialogue in a film as a variation. The accumulation of variations is important to me too.” But to enrich the repetition and variations, he also makes use of randomness, “the idea of finding things as you go along and finding links between things you weren’t even looking to link.”

Jarmusch credits this way of thinking to William S. Burroughs (author, incidentally, of an essay called “The Limits of Control”), and specifically the “cut-up” technique, which Burroughs and the artist Brion Gysin came up with, literally cutting up texts in order to then “mix words and phrases and chapters together in a random way.” He’s also found a source of randomness in the Oblique Strategies, the deck of cards published in the 1970s by artist and music producer Brian Eno and painter Peter Schmidt. “You just pick one card and it might say something like, ‘Listen from another room.’ One of my favorite cards says, ‘Emphasize repetitions.’ ” That last comes as no surprise, and he surely also appreciates the one that says, “Repetition is a form of change.”

Those who know both the Oblique Strategies and Jarmusch’s filmography — from his breakout indie hit Stranger Than Paradise to recent work like Paterson, the story of a bus-driving poet in William Carlos Williams’ hometown — could think of many that apply to his signature cinematic style: “Disconnect from desire,” “Emphasize the flaws,” “Use ‘unqualified’ people,” “Remove specifics and convert to ambiguities” (or indeed “Remove ambiguities and convert to specifics”). His next project, which will feature regular collaborators Bill Murray and Tilda Swinton as well as such newcomers to the Jarmusch fold as former teen pop idol Selena Gomez, should offer another satisfying set of variations on his usual themes. And given that it’s about zombies, it will no doubt come with a strong dose of randomness as well.

Related Content:

Jump Start Your Creative Process with Brian Eno’s “Oblique Strategies” Deck of Cards (1975)

Marshall McLuhan’s 1969 Deck of Cards, Designed For Out-of-the-Box Thinking

How to Jumpstart Your Creative Process with William S. Burroughs’ Cut-Up Technique

How David Bowie, Kurt Cobain & Thom Yorke Write Songs With William Burroughs’ Cut-Up Technique

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.