“Tell all the truth but tell it slant,” wrote Emily Dickinson, “Success in Circuit lies.” No doubt she had more literary, or metaphysical, matters in mind than scientific. But for scientists working in times hostile to change, telling the truth, as they know it, can be dangerous. This applies to EPA scientists working today as it did 400 years ago to European astronomers, who faced censure—with possibly fatal consequences—for contradicting the official version of reality dictated by the Catholic Church and enforced by the Inquisition.

The story of Galileo Galilei’s infamous confrontation with what the Rice University Galileo Project calls that “permanent institution” of the Church, “charged with the eradication of heresies,” has swelled into legend, with the astronomer playing the part of a martyr for reason and evidence. Other versions, like Bertolt Brecht’s play Galileo, portray him, writes The New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik, not as “a martyr-hero but a turncoat, albeit one of genius.” Rather than standing on principle, he hedged and compromised.

A “newer (and, unsurprisingly, Church-endorsed) view,” writes Gopnik, “is that Galileo made needless trouble for himself by being impolitic,” and that all the poor Church wanted, “as today’s intelligent designers now say,” was to “’teach the controversy’” between Copernican and Aristotelian theories. Whatever their interpretation, historians of the events leading up to Galileo’s conviction for heresy after the publication of his Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems now have a new piece of evidence to add to their assessment.

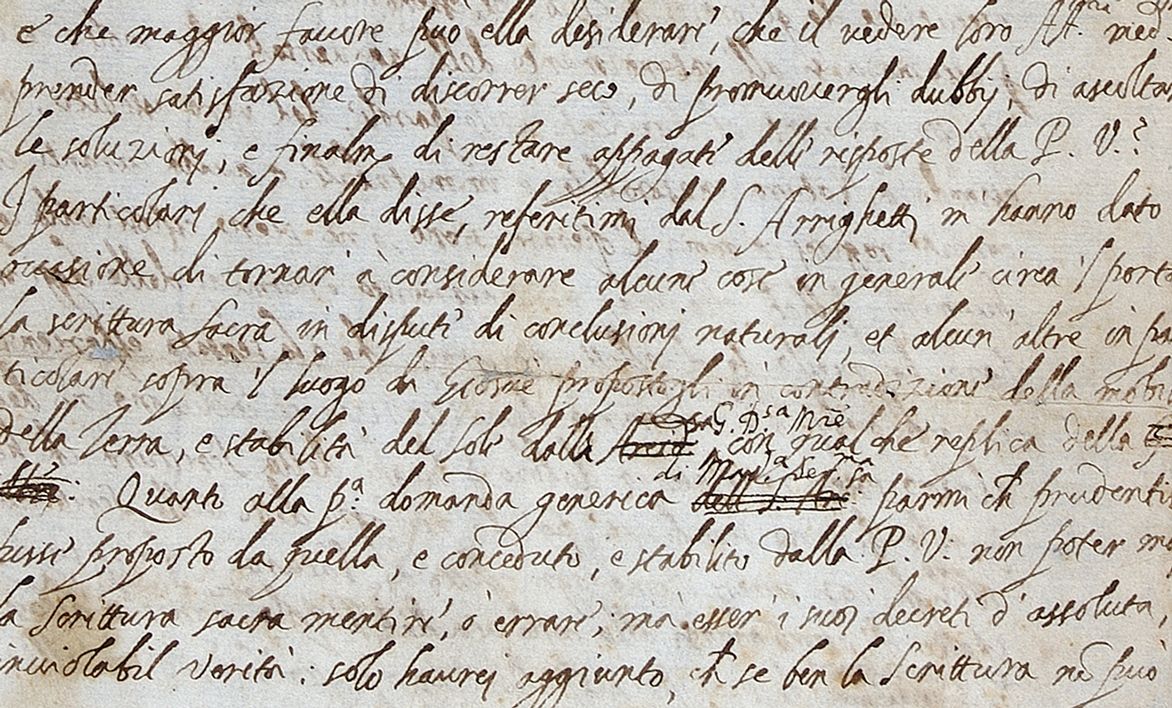

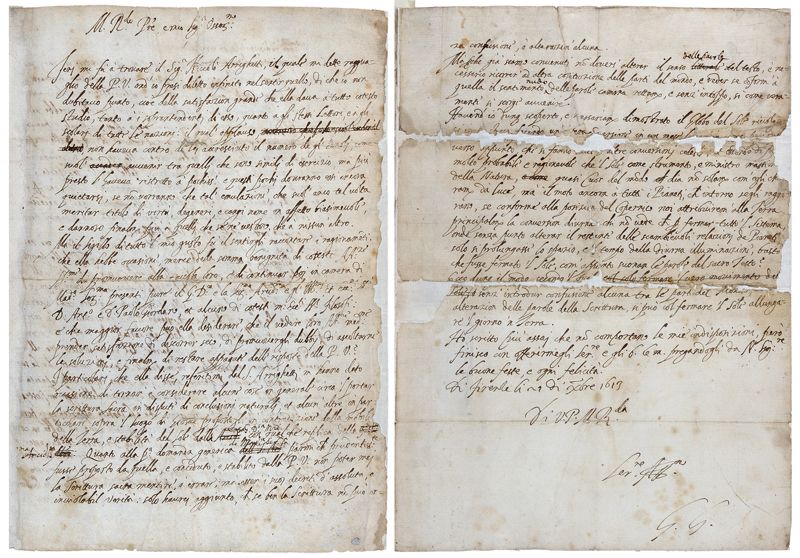

A letter, “long thought lost,” Nature reports, has reappeared, providing “the strongest evidence yet that, at the start of his battle with the religious authorities, Galileo actively engaged in damage control and tried to spread a toned-down version of his claims.” In the seven-page document, written to his friend Benedetto Castelli in 1613, Galileo “set out for the first time his arguments that scientific research should be free from theological doctrine.” Furthermore, and most damningly for him:

He argued that the scant references in the Bible to astronomical events should not be taken literally, because scribes had simplified these descriptions so that they could be understood by common people. Religious authorities who argued otherwise, he wrote, didn’t have the competence to judge. Most crucially, he reasoned that the heliocentric model of Earth orbiting the Sun, proposed by Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus 70 years earlier, is not actually incompatible with the Bible.

Copies of the controversial letter circulated, and inevitably made their way into the hands of Inquisition authorities in 1615, forwarded by a Dominican friar named Niccolò Lorini. Alarmed, Galileo “wrote to his friend Piero Dini, a cleric in Rome, suggesting that the letter Lorini had sent to the Inquisition might have been doctored.” He enclosed another, less inflammatory, version, which he claimed was the original. He wrote of the “wickedness and ignorance” of those he claimed had tried to frame him. The Inquisitors, he wrote “may be in part deceived by this fraud which is going around under the cloak of zeal and charity.”

Historians have long known of the two letters, but were uncertain as to whose version of events to believe. The original of the Lorini copy was thought to have been lost, until its recent discovery by postdoctoral science historian Salvatore Ricciardo, who found it, of all places, in the Royal Society library, where it had sat unnoticed for 250 years. The original letter, which Castelli had returned to Galileo, shows edits in his own hand. “Beneath its scratchings-out and amendments, the signed copy discovered by Ricciardo shows Galileo’s original wording—and it is the same as in the Lorini copy” that landed him in trouble.

The evidence proves that Galileo strongly advocated for the Copernican system, and against Church interference in free inquiry, in 1613. In one passage of the letter, originally describing the Bible as “false if one goes by the literal meaning of the words,” Galileo crosses out “false” and inserts “look different from the truth.” In another reference to scripture as “concealing” the truth, he opts for the more theological-sounding “veiling.” The letter shows Galileo softening his views to escape condemnation, but it does not show him recanting in any way.

In 1616, the year after the Church received a copy of the first letter from Lorini and Galileo’s doctored version, he was warned to stop arguing for the Copernican model, though he later received assurances from Pope Urban VIII that he could continue to write about heliocentrism if he presented the idea as a mathematical proposition rather than a statement of fact. Of course, as we know, his continued support for the science earned him permanent house arrest in 1633, and centuries of enduring admiration from the opponents of dogmatic suppression of scientific knowledge.

via Nature

Related Content:

How a Book Thief Forged a Rare Edition of Galileo’s Scientific Work, and Almost Pulled it Off

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply