William Blake earned his place as the patron saint of all freethinking outsider artists. One might say he perfected the role as he perfected his art—or his arts rather, since his poetry inspires as much awe and acclaim as his visionary engravings and illustrations. Standing astride the Neoclassical eighteenth century and the Romantic era, Blake rejected the rationalism and classicism that surrounded him from birth and developed a prophetic style drawn from an earlier age.

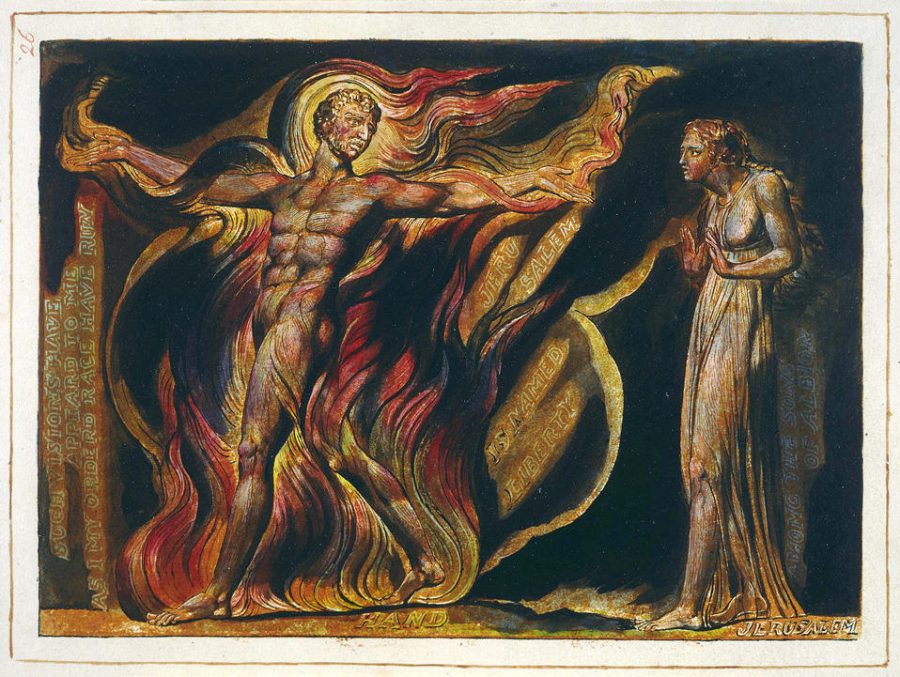

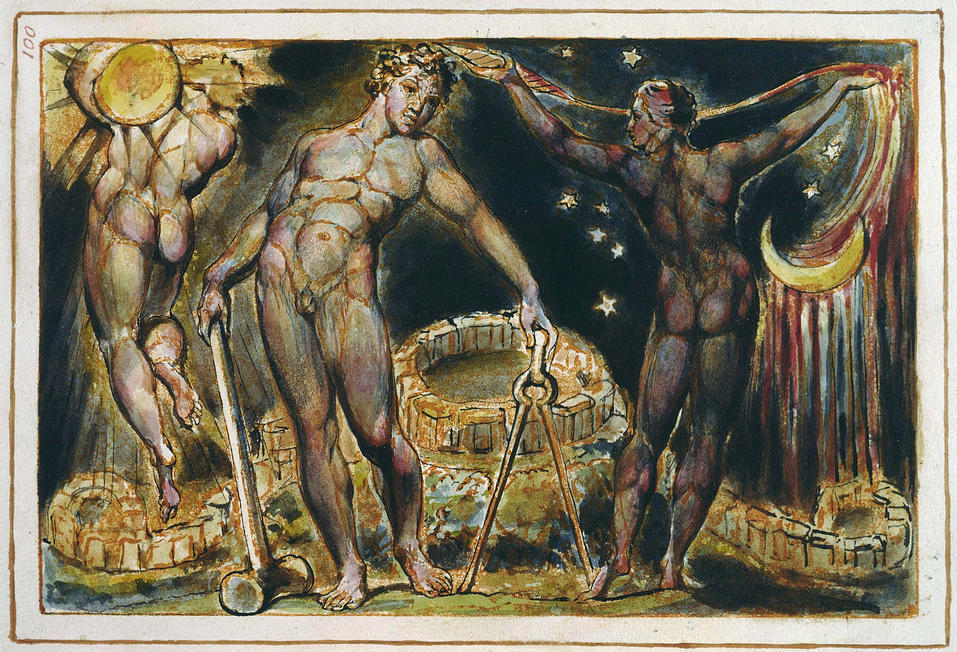

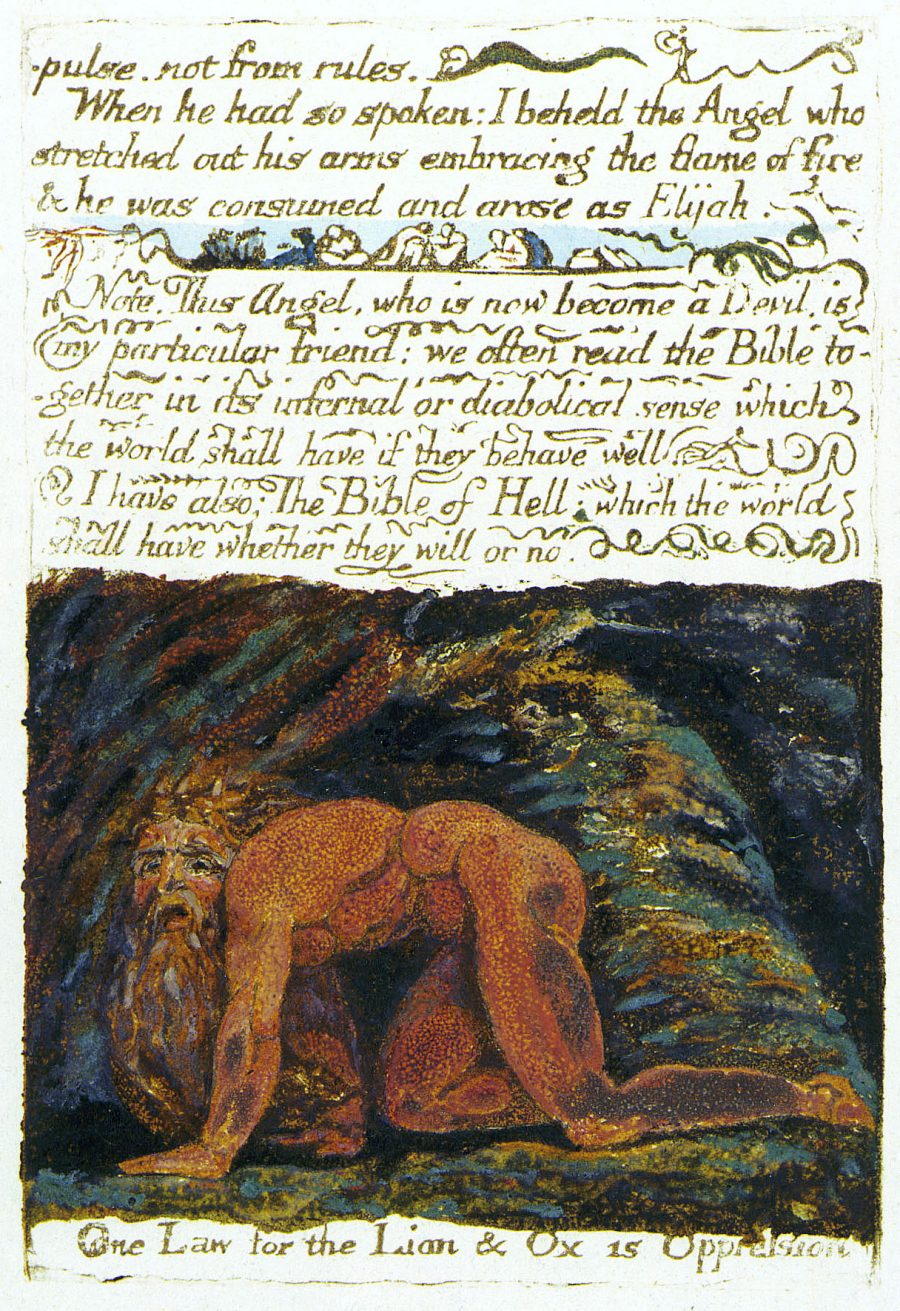

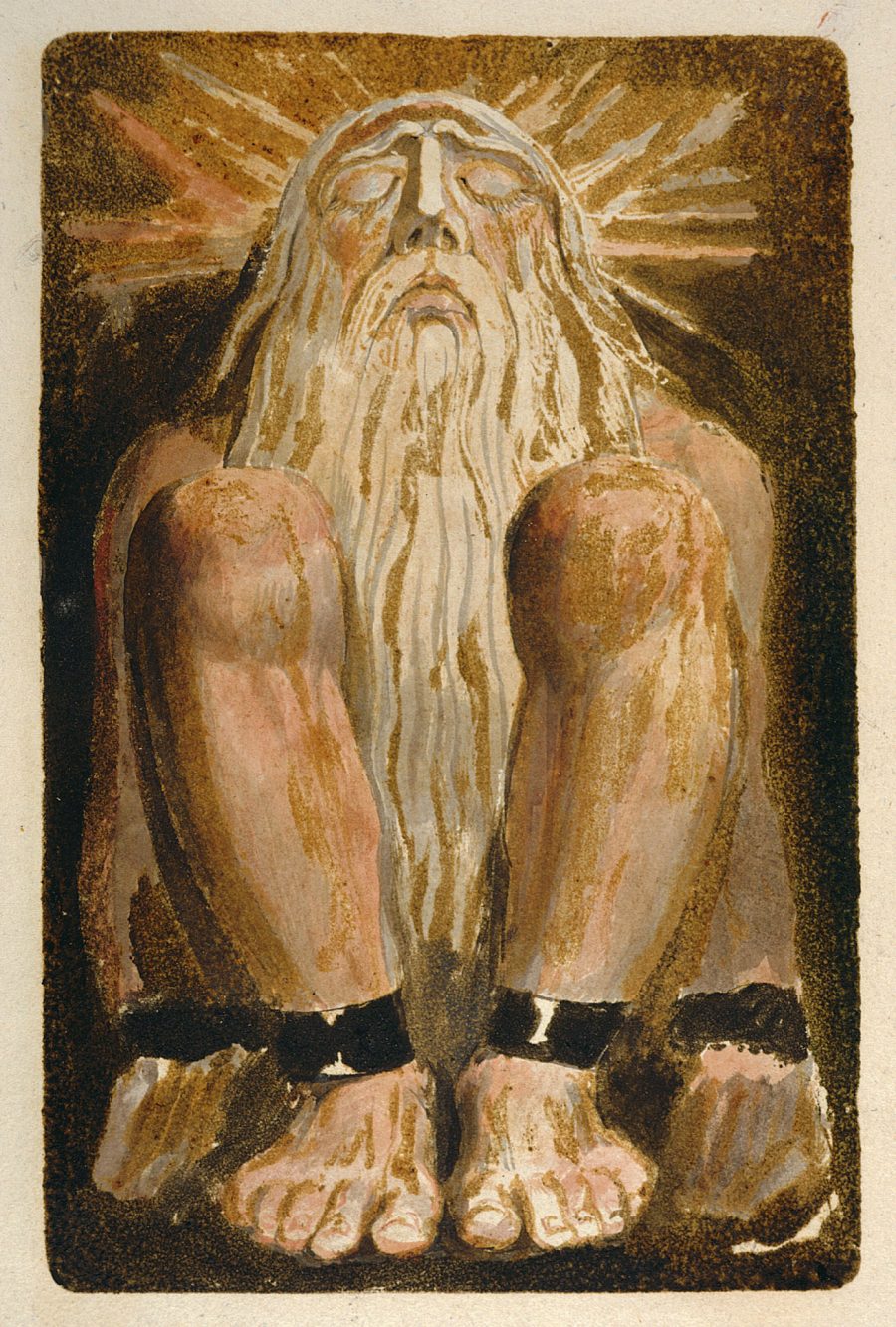

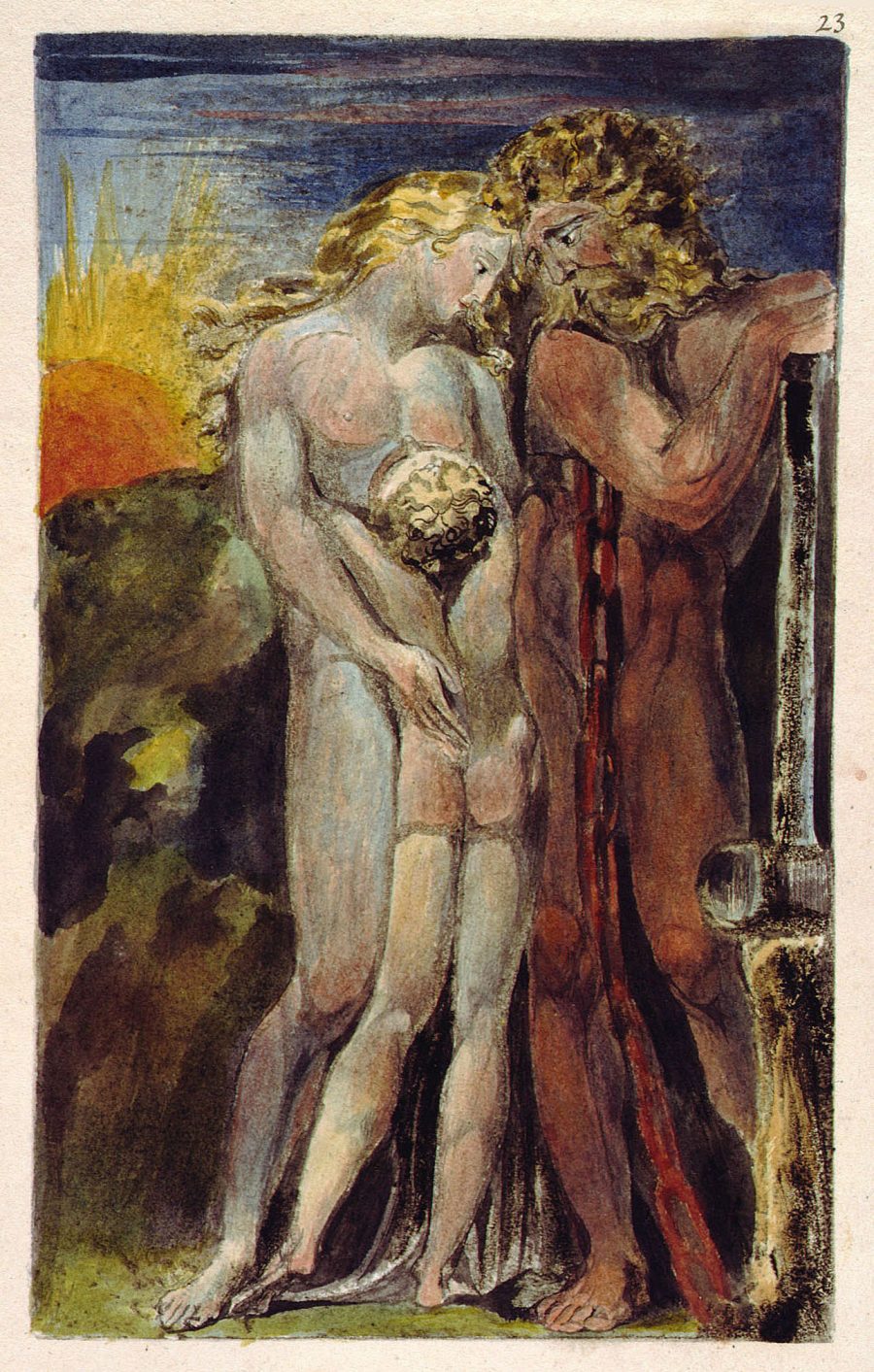

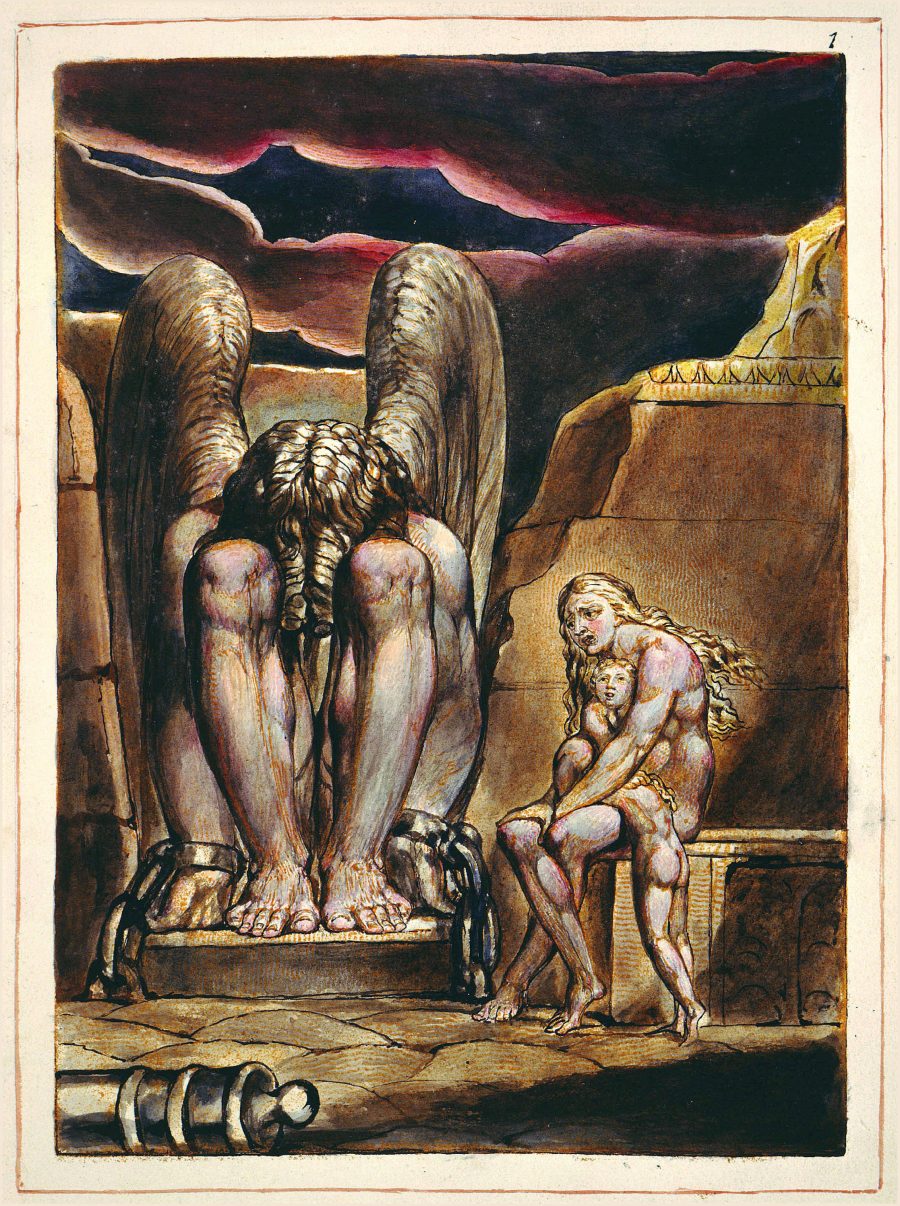

He “sought to emulate the example of artists such as Raphael, Michelangelo and Dürer in producing timeless, ‘Gothic’ art, infused with Christian spirituality and created with poetic genius,” writes the Met’s Elizabeth Barker. (“Blake described his painting technique as ‘fresco.’) But no one would ever mistake the works of Blake for anyone other than Blake, with their muscular, heroic figures, violently expressive faces, and tortured poses.

The William Blake Archive gives us access to a huge sampling of Blake’s work, from his book illustrations to his drawings and paintings, to his manuscripts, etc. The images are high resolution scans that users can add to a lightbox, rotate, zoom into, view “true size,” or enlarge.

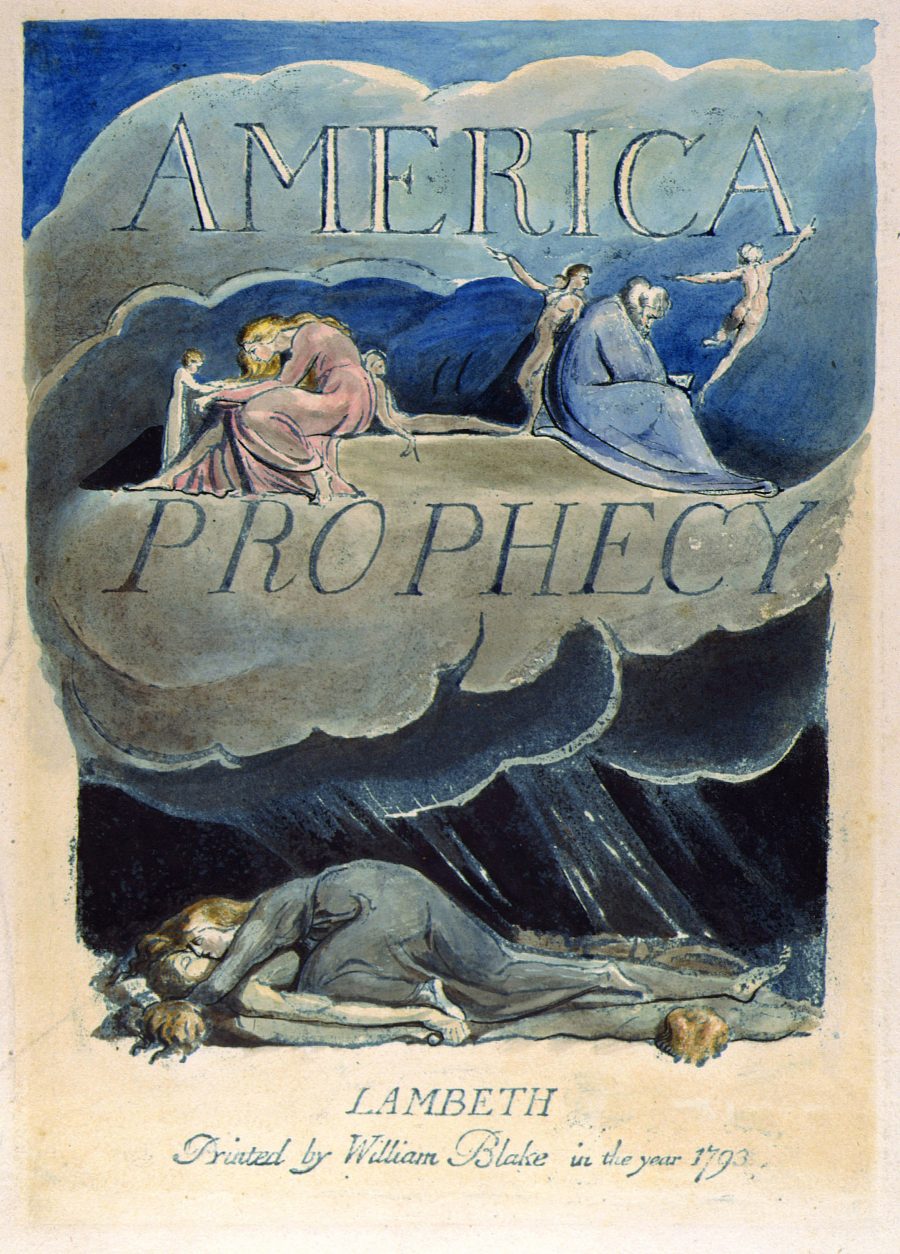

Perhaps most interesting are the images, like those here, from Blake’s “Illuminated Books,” a series of philosophical, religious, and mythological works composed from about 1788 to 1822. The archive contains dozens of variant printings of these endlessly fascinating hand-lettered books.

Becoming a furiously prolific, mystically inspired artist while living in poverty and near-obscurity—“considered insane and largely disregarded by his peers,” as BBC History puts it—required fortitude and almost superhuman belief in himself, especially since his belief system was largely self-created. While Blake considered the Bible “the greatest work of poetry ever written,” and its themes and narratives spoke to him throughout his career, his own religious tendencies took the form of the mythology he elaborated through the fantastical illuminated books.

“I must Create a System,” he wrote in Jerusalem, composed between 1804 and 1820, “or be enslav’d by another Mans,” and so he did, inventing figures like Los, Urizen (the oppressive, suppressive God of the Old Testament), Albion, the personification of England, and his daughters, Bromion, Oothoon, and Theotormon. While working on these unorthodox projects, he barely “eked out a living as an engraver and illustrator” of commercial books. He also drew and painted several Biblical subjects and scenes from literary texts by his favorite authors, Milton and Dante.

The illuminated books, Barker writes “rank among Blake’s most celebrated achievements.” Written “in a range of forms—prophecies, emblems, pastoral verses, biblical satire, and children’s books,” these eclectic works “addressed various timely subjects—poverty, child exploitation, racial inequality, tyranny, religious hypocrisy.” With literary vigor, moral clarity, and emotional insight, Blake harshly critiqued what he saw as the evils of his age, and moreover, offered an alternative—an anti-Enlightenment, radically egalitarian, free love vision, composed of patchwork elements of the Bible, Milton, Emanuel Swedenborg, and pagan and druidic sources.

Two of the most famous of Blake’s illuminated books show the influence of Milton’s Il Penseroso and L’Allegro, studies in the contrast of melancholy and mirth, which Blake once illustrated. In Blake’s hands, these become Songs of Innocence, “the gentlest of his lyrics,” writes BBC, and Songs of Experience, “containing a profound expression of adult corruption and repression.” Blake also found in Dante “a seemingly inexhaustible source of inspiration in his own fertile mind,” Barker explains. But just as he transformed his artistic influences, he took his literary inspirations in directions no one else but Blake would think to do. And for that, he remains a singularly original artist, peerless in inventiveness and dedication to his work.

See the William Blake Archive here. The link to his “Illuminated Books” from which the images here come is at the top left-hand corner of the archive’s nav bar.

You can purchase a copy of William Blake: The Complete Illuminated Books in book format here.

Related Content:

William Blake’s Hallucinatory Illustrations of John Milton’s Paradise Lost

William Blake’s Masterpiece Illustrations of the Book of Job (1793–1827)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

beautiful

classic

Nice and cool website.