For a book about medieval theology and torture, filled with learned classical allusions and obscure characters from 13th century Florentine society, Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, first book of three in his Divine Comedy, has had considerable staying power, working its way into pop culture with a video game, several films, and a baleful appearance on Mad Men. While the Mad Men reference may be the more literary, the former two may hint at the more prominent reason the Inferno has captivated readers, players, and viewers for ages: the lengthy poem’s intensely visual representation of human extremity makes for some unforgettable images. Like Achilles dragging Hector behind his chariot in Homer, who can forget the lake of ice Dante encounters in the ninth circle of Hell, in which (in John Ciardi’s modern translation), he finds “souls of the last class,” which “shone below the ice like straws in glass,” and, frozen to his chest, “the Emperor of the Universe of Pain,” almost too enormous for description and as hideous as he once was beautiful.

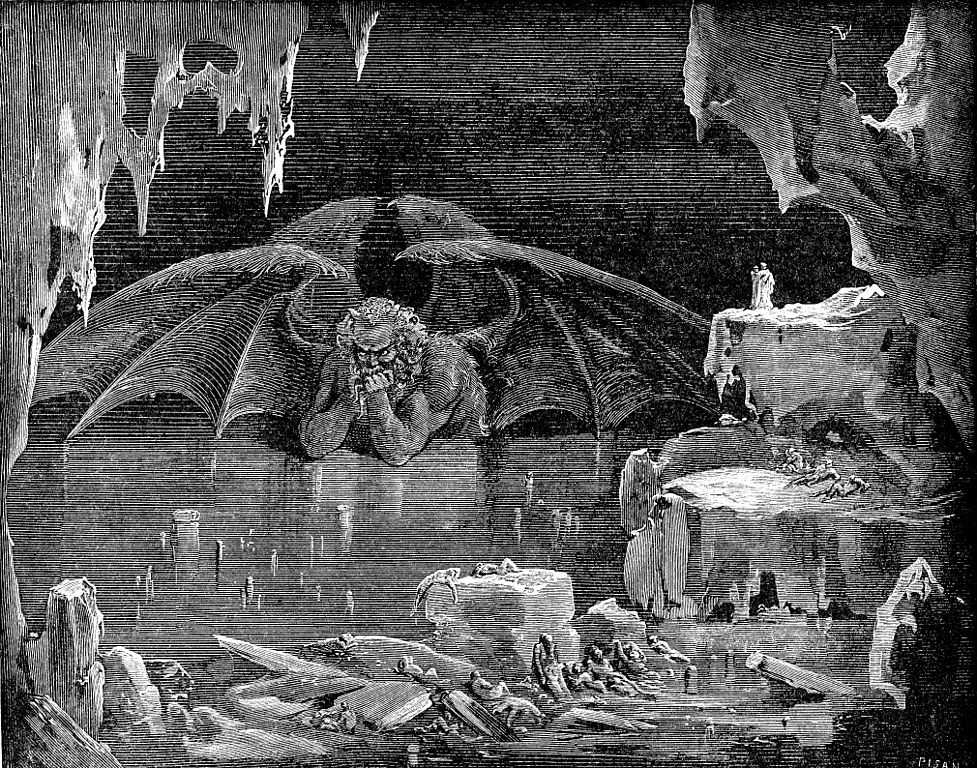

Like the rest of us, artists have been drawn to Dante’s extraordinary images and extensive fantasy geography since the Divine Comedy first appeared (1308–1320). In prolific French artist Gustave Doré’s rendering of the ninth circle scene, above, Satan is a huge, bearded grump with wings and horns. Doré so desperately wanted to illustrate the Divine Comedy (find in our collection of 700 Free eBooks) that he financed the first book in 1861 with his own money.

Afterwards, as Mike Springer wrote in a previous post on Dore’s illustrations, his publisher Louis Hachette agreed to put out the next two books with the telegram, “Success! Come quickly! I am an ass!” Doré’s eerie, beautiful drawings are just one such set of famous illustrations we’ve featured on the site previously.

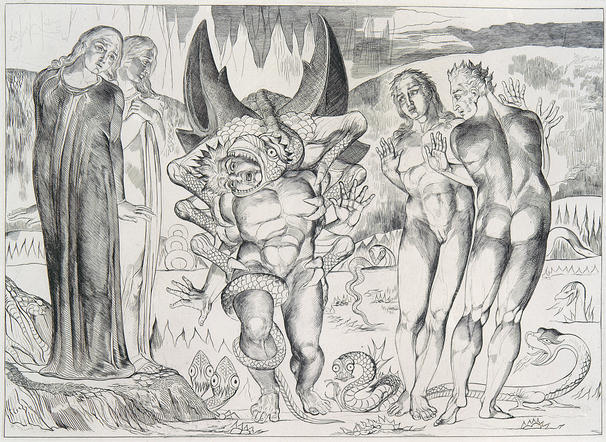

Another artist perfectly suited to the task, William Blake, whose own poetry braved similar heights and depths as Dante’s, took on the Inferno at the end of his life. While he didn’t live to complete the engravings, his unsettling, yet highly classical, renderings of the poet the Italians call il Sommo Poeta—“The Supreme Poet”—certainly do justice to the vividness and horror of Dante’s descriptions. Above, see Blake’s 1827 interpretation of the thief Agnolo Brunelleschi attacked by a six-footed serpent in Canto twenty-five, a scene reprinted many times in color.

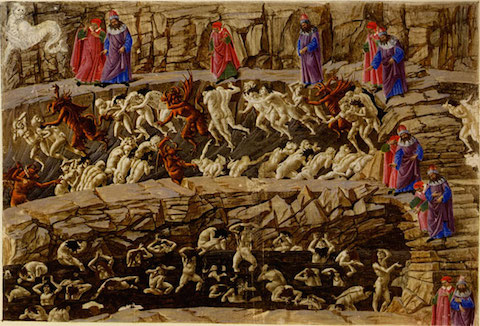

Centuries earlier, Renaissance master Sandro Botticelli made an attempt at all three books, though he fell short of finishing them. See his “Panderers, Flatterers” above, the only drawing he made in color, and more black and white illustrations here.

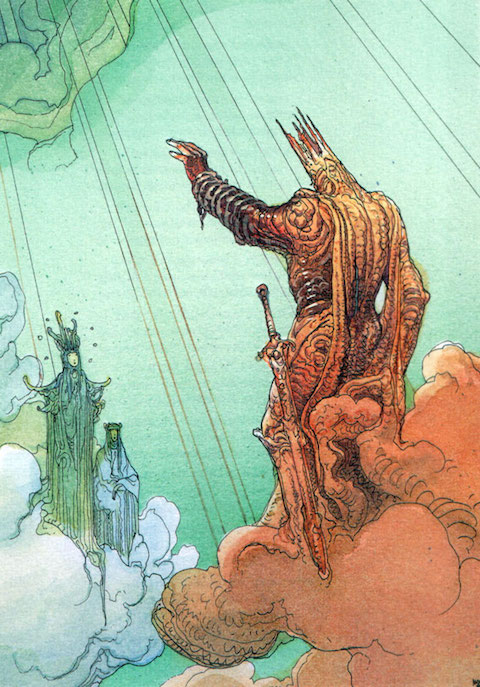

Like the makers of films and video games, artists have mainly chosen to focus on the most bizarre and harrowing of the three books, the Inferno. One modern artist who undoubtedly would have had a fascinating take on Dante’s hell instead illustrated his heaven, being chosen to imagine Paradiso by the Milan’s Nuages Gallery in 1999. I refer to graphic artist Jean Giraud, known in the world of fantasy, sci-fi, and comics as Mœbius. Despite some arguable artistic miscasting (Mœbius did after all make films like Alien and Tron “even weirder”), the French artist took what may be the least visually interesting of Dante’s three Divine Comedy books and created some incredibly striking images. See one above, and more at our previous post.

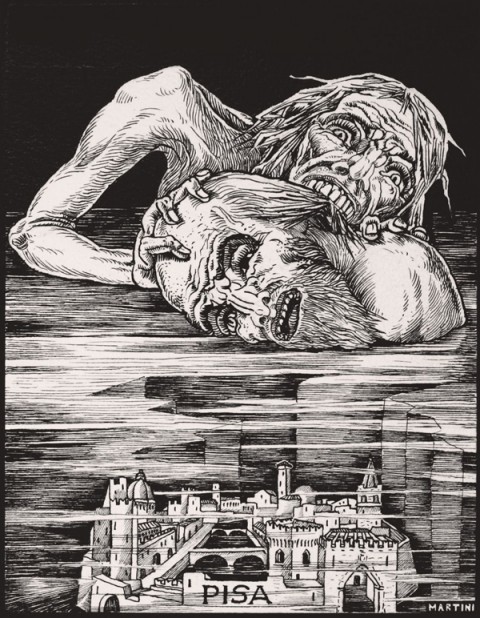

Other artists, like Alberto Martini, who worked on his Divine Comedy for over forty years, have produced terrifying images (above) and highly stylized ones—like these medieval illuminations from a 1450 manuscript. The range of interpretations all have one thing in common—their subject matter seems to allow artists almost unlimited freedom to imagine Dante’s weird cosmography. No vision of the Inferno or the loftier realms above it can go too far, it seems, even in the absurd video game finale you really have to see to believe. Somehow, I think Dante would approve… well… mostly.

Related Content:

Gustave Doré’s Exquisite Engravings of Cervantes’ Don Quixote

William Blake’s Hallucinatory Illustrations of John Milton’s Paradise Lost

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Michael Mazur’s illustrations should be included here, truly incredible.

Japanese Manga legend Go Nagai shoul be included as well: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/23119668-la-divina-commedia-vol‑i