Happy New Year!

We can now “do to Disney what Disney did to the great works of the public domain before him,” according to Harvard law professor and public domain expert, Lawrence Lessig, hailed by The New Yorker as “the most important thinker on intellectual property in the Internet era.”

On January 1, Mickey Mouse and his consort, Minnie, wriggled free of their creator’s iron fist for the first time in corporate history, as their debut performance in Steamboat Willie entered the public domain along with thousands of other 1928 works — Lady Chatterley’s Lover, All Quiet on the Western Front, and The House at Pooh Corner to name but a starry few.

Disney has been notoriously protective of its control over its spokesmouse, successfully pushing Congress to adopt the Sonny Bono Copyright Extension Act of 1998, which kept the public’s mitts off of Steamboat Willie, and, more to the point, Mickey Mouse, for 25 years beyond the terms of the Copyright Act of 1976.

But now our day has come…

Don’t be shy!

Dig in!

Disney always did.

As Lessig remarked in a 2003 lecture at Princeton University:

Walt Disney embraced the freedom to take, change and return ideas from our popular culture. The rip, mix and burn culture of the Internet is Disney-familiar.

Cinderella, Snow White, Pinocchio — Uncle Walt knew how to take liberties and make money with captivating source material, a tradition that continued through such later cartoon blockbusters as The Little Mermaid and Disney’s Snow Queen update, Frozen.

Steamboat Willie wasn’t conjured from thin air either. Its plot and title character were inspired by Buster Keaton’s Steamboat Bill, released two months before Disney’s animated short went into production.

A few caveats for those eager to take a crack at the Mouse…

Steamboat Willie’s newfound public domain status doesn’t give you carte blanche to mess around with Mickey and Minnie in all their many forms.

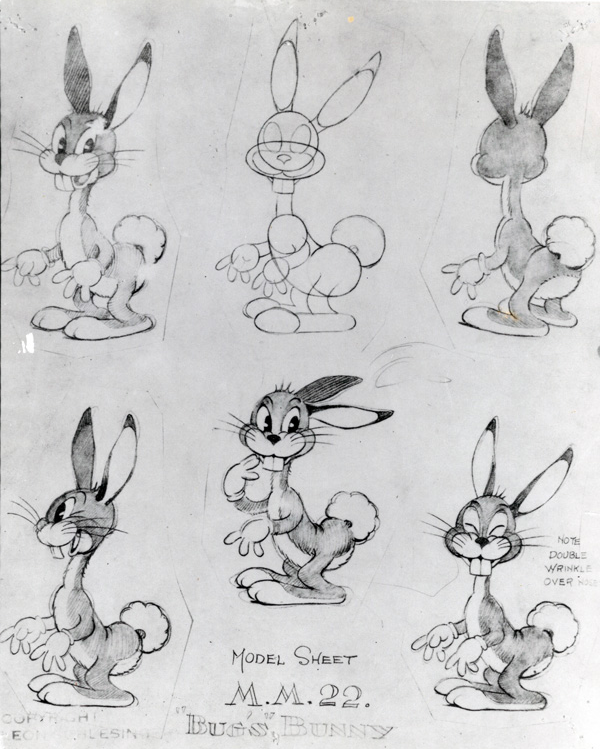

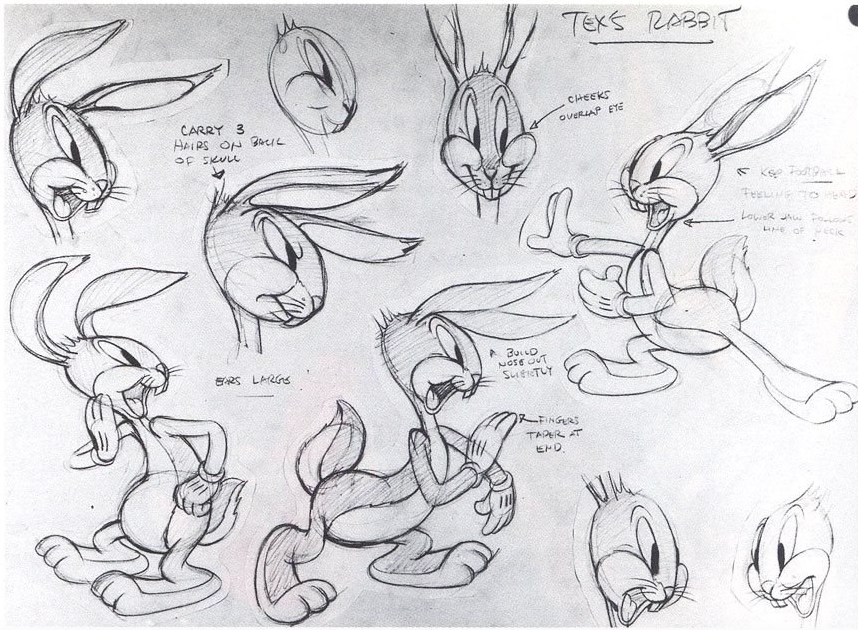

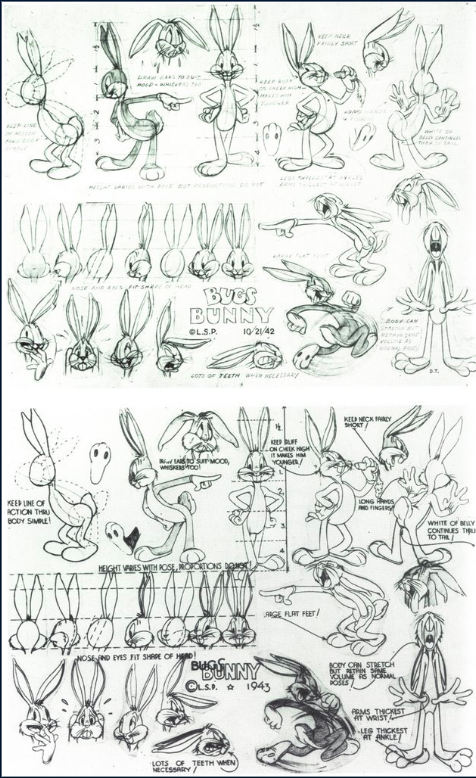

Stick to the music-loving black-and-white trickster with rubberhose arms, button-trimmed short-shorts, and the distinctly rodent-like tail that went by the wayside for Mickey’s appearance in 1941’s The Little Whirlwind.

Nor can Steamboat Willie-era Mickey become your new logo. Plop the character down in new narratives, yes. Use him in a recognizable way for purposes of advertising unrelated products, no.

Mislead viewers into thinking your mash up is Disney-approved at your own risk. A Disney spokesperson told CNN:

We will, of course, continue to protect our rights in the more modern versions of Mickey Mouse and other works that remain subject to copyright, and we will work to safeguard against consumer confusion caused by unauthorized uses of Mickey and our other iconic characters.

Don’t think they don’t mean it.

Author Robert Thompson, the founding director of Syracuse University’s Bleier Center for Television and Popular Culture told The Guardian that even though “the original Mickey isn’t the one we all think of and have on our T‑shirts or pillowcases up in the attic someplace,” the company is hypervigilant about protecting its assets:

Symbolically of course, copyright is important to Disney and it has been very careful about their copyrights to the extent that laws have changed to protect them. This is the only place I know that some obscure high school in the middle of nowhere can put on The Lion King and the Disney copyright people show up.

Perhaps your best bet is to make sure your work skews toward satire or parody, a la the infamous horror film Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey, which capitalized on author A.A. Milne’s 1926 book, Winnie the Pooh’s entrance into the public domain, while trafficking in some familiar character design. Disney ultimately let it slide.

Fumi Games is already poised to take a similar gamble with MOUSE, a blood-soaked, “gritty, jazz-fueled shooter” set to drop in 2025:

If you’re not yet ready to take the plunge, Mickey’s pals Pluto and Donald Duck will join him in the public domain later this decade, so don your thinking caps and mark your calendars.

For a more in-depth look at the ways you can — and cannot — use Steamboat Willie-era Mickey Mouse in your own work, Duke University’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain supplies a very thorough guide here.

Related Content

The Disney Cartoon That Introduced Mickey Mouse & Animation with Sound (1928)

“Evil Mickey Mouse” Invades Japan in a 1934 Japanese Anime Propaganda Film

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Her variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain, returns to New York City on February 29, 2024. Follow her @AyunHalliday.