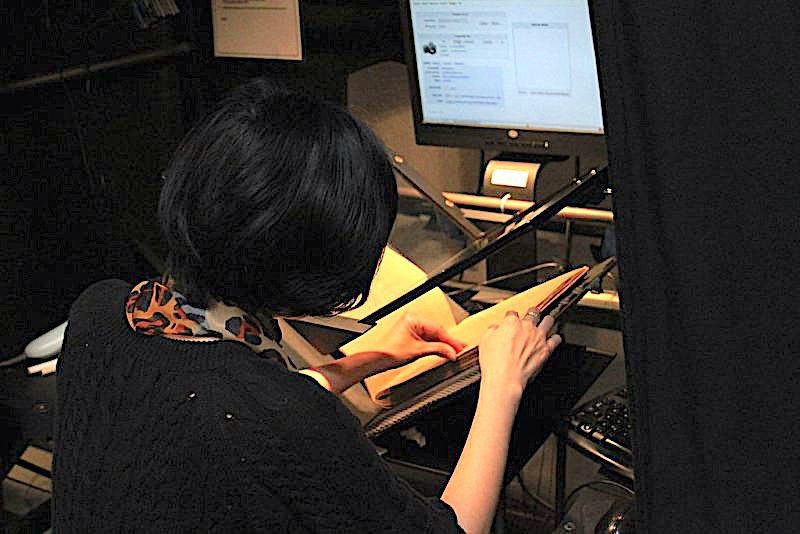

At the Internet Archive, this is how we digitize #78 rpm records.

Our partner @georgeblood_lp has perfected this technique, digitizing with 4 different styli at once.We put as much effort into capturing the #metadata as we do digitizing the music. pic.twitter.com/dn4EjXTS9z

— Internet Archive (@internetarchive) April 25, 2021

In the history of recorded music, no medium has demonstrated quite the staying power of the phonograph record. Hearing those words, most of us envision a twelve-inch disc designed to play at 33 1⁄3 revolutions per minute, the kind still manufactured today. But like every other form of technology, that familiar vinyl LP didn’t appear ex nihilo: on its introduction in 1948, it was the latest in a series of phonograph records of different sizes and speeds. The first dominant record format spun at 78 r.p.m., a speed standardized in the mid-1920s, though the discs themselves (made of rubber, shellac, or other pre-vinyl materials) had been in production since the end of the 19th century and remained in production until the 1950s.

The half-century of the “78” adds up to quite a lot of music, most of which has long been inaccessible to non-antiquarians. Enter the historically minded technologists of the Internet Archive, who since 2016 have been working with media preservation company George Blood LP to digitize, preserve, and make available, as of this writing, more than 250,000 such records.

The process involves much more than playing them all into a computer, due not least to the toll the past century or so has taken on the discs’ surfaces. “Each record is cleaned on a machine that sprays distilled water onto its surface,” writes The Verge’s Kait Sanchez. “A little vacuum arm then sucks up the water, along with whatever dirt and nastiness has built up in the record’s grooves.”

“The discs are then photographed, and the photos are referenced to pull info from the discs’ labels and add it to the archive’s database by hand.” There follows the actual digitization, which records each disc with four styli at once: since 78s never had standardized groove sizes, “recordings taken with various stylus tips will each sound slightly different,” but for any record in the George Blood Collection the listener can choose which of the four they’d prefer to listen through. You can see each step of the process in the video at the top of the post, part of a Twitter thread recently posted by the Internet Archive. There the Archive notes that, “after scanning 250,000 sides, we’ve found 80% of these 78s were produced by the ‘Big Five’ labels” — Columbia, RCA Victor, Decca, Capitol and Mercury — “but along the way, we’ve uncovered 1700 other music labels and some pretty beautiful picture discs.”

You can look at — and more to the point, listen to — everything in the the George Blood Collection here, which is a subset of the Internet Archive’s larger collection of digitized 78 records as well as the cylinders that 78s wholly displaced as a consumer format. As the Internet Archive’s Twitter thread reminds us, “from 1898–1950, this was THE way music was recorded & shared.” In other words, if your parents were listening to music in that period — or maybe your grandparents, great-grandparents, or great-great grandparents — 78s were their MP3s, their Spotify, their Youtube. We descend as listeners from enthusiastic buyers of 78s, and now, thanks to the Internet Archive and its collaborators, we can enjoy a large and ever-increasing proportion of their entire world of recorded music for free.

Related Content:

The Boston Public Library Will Digitize & Put Online 200,000+ Vintage Records

The Groundbreaking Art of Alex Steinweiss, Father of Record Cover Design

How the Internet Archive Digitizes 3,500 Books a Day–the Hard Way, One Page at a Time

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.