It should go without saying that one should drink responsibly, for reasons pertaining to life and limb as well as reputation. The ubiquity of still and video cameras means potentially embarrassing moments can end up on millions of screens in an instant, copied, downloaded, and saved for posterity. Not so during the infancy of photography, when it was a painstaking process with minutes-long exposure times and arcane chemical development methods. Photographing people generally meant keeping them as still as possible for several minutes, a requirement that rendered candid shots next to impossible.

We know the results of these early photographic portraiture from many a famous Daguerreotype, named for its French inventor, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre. At the same time, during the 1830s and 40s, another process gained popularity in England, called the Calotype—or “Talbotype,” for its inventor William Henry Fox Talbot. “Upon hearing of the advent of the Daguerreotype in 1839,” writes Linz Welch at the United Photographic Artists Gallery site, Talbot “felt moved to action to fully refine the process that he had begun work on. He was able to shorten his exposure times greatly and started using a similar form of camera for exposure on to his prepared paper negatives.”

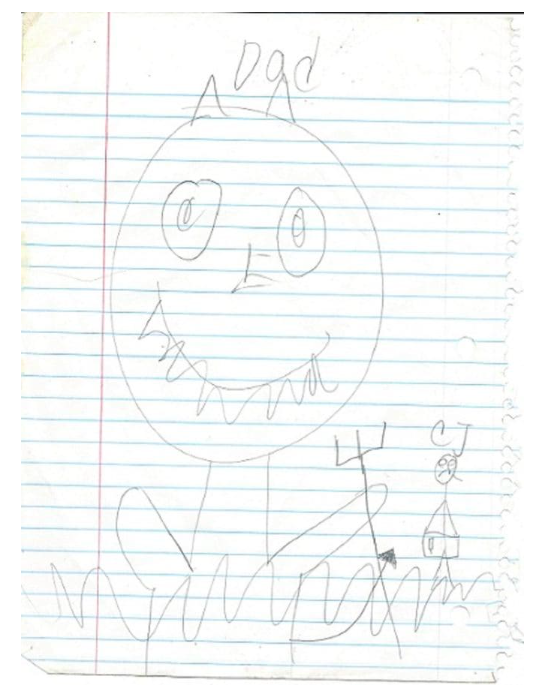

This last feature made the Calotype more versatile and mechanically reproducible. And the shortened exposure times seemed to enable some greater flexibility in the kinds of photographs one could take. In the 1843 photo above, we have what appears to be an entirely unplanned grouping of revelers, caught in a moment of cheer at the pub. Created by Scottish painter-photographers Robert Adamson and David Octavius Hill—who grins, half-standing, on the right—the image looks like almost no other portrait from the time. Rather than sitting rigidly, the figures slouch casually; rather than looking grim and mournful, they smile and smirk, apparently sharing a joke. The photograph is believed to be the first image of alcoholic consumption, and it does its subject justice.

Though Talbot patented his Calotype process in England in 1841, the restrictions did not apply in Scotland. “In fact,” the Metropolitan Museum of Art writes, “Talbot encouraged its use there.” He maintained a correspondence with interested scientists, including Adamson’s older brother John, a professor of chemistry. But the Calotype was more of an artists’ medium. Where Daguerreotypes produced, Welch writes, “a startling resemblance of reality,” with clean lines and even tones, the Calotype, with its salt print, “tended to have high contrast between lights and darks…. Additionally, because of the paper fibers, the image would present with a grain that would diffuse the details.” We see this especially in the capturing of Octavius Hill, who appears both lifelike in motion and rendered artistically with charcoal or brush.

The other two figures—James Ballantine, writer, stained-glass artist, and son of an Edinburgh brewer, and Dr. George Bell, in the center—have the rakish air of characters in a William Hogarth scene. The National Galleries of Scotland attributes the naturalness of these poses to “Hill’s sociability, humour and his capacity to gauge the sitters’ characters.” Surely the booze did its part in loosening everyone up. The three men are said to be drinking Edinburgh Ale, “according to a contemporary account… ‘a potent fluid, which almost glued the lips of the drinker together.’ ” Such a side effect would, at least, make it extremely difficult to over-imbibe.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2017.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content

The First Photograph Ever Taken (1826)

See The First “Selfie” In History Taken by Robert Cornelius, a Philadelphia Chemist, in 1839

See the First Photograph of a Human Being: A Photo Taken by Louis Daguerre (1838)

The First Faked Photograph (1840)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness