It’s bittersweet whenever a pioneering, long overlooked female scientist is finally given the recognition she deserves, especially so when the scientist in question is a person of color.

Chemist Alice Ball’s youth and drive — just 23 in 1915, when she discovered a gentle, but effective method for treating leprosy — make her an excellent role model for students with an interest in STEM.

But in a move that’s only shocking for its familiarity, an opportunistic male colleague, Arthur Dean, finagled a way to claim credit for her work.

We’ve all heard the tales of female scientists who were integral team players on important projects, who ultimately saw their role vastly downplayed upon publication or their names left off of a prestigious award.

But Dean’s claim that he was the one who had discovered an injectable water-soluble method for treating leprosy with oil from the seeds of the chaulmoogra fruit is all the more galling, given that he did so after Alice Ball’s tragically early death at the age of 24, suspected to be the result of accidental poisoning during a classroom lab demonstration.

Not everyone believed him.

Ball, the University of Hawaii chemistry department’s first Black female graduate student, and, subsequently, its first Black female chemistry instructor, had come to the attention of Harry T. Hollmann, a U.S. Public Health Officer who shared her conviction that chaulmoogra oil might hold the key to treating leprosy.

After her death in 1916, Hollmann reviewed Dean’s publications regarding the highly successful new leprosy treatment then referred to as the Dean Method and wrote that he could not see “any improvement whatsoever over the original [method] as worked out by Miss Ball:”

After a great amount of experimental work, Miss Ball solved the problem for me by making the ethyl esters of the fatty acids found in chaulmoogra oil.

Type “the Dean Method leprosy” into a search engine and you’ll be rewarded with a satisfying wealth of Alice Ball profiles, all of which go into detail regarding her discovery of what became known as the Ball Method, in use until the 1940s.

Kathleen M. Wong’s article on this trailblazing scientist in the Smithsonian Magazine delves into why Hollmann’s professional efforts to posthumously confer credit where credit was due were insufficient to secure Ball her rightful place in science history.

That began to change in the 1990s when Stan Ali, a retiree researching Black people in Hawaii, found his interest piqued by a reference to a “young Negro chemist” working on leprosy in The Samaritans of Molokai.

Ali teamed up with Paul Wermager, a retired University of Hawaii librarian, and Kathryn Waddell Takara, a poet and professor in the Ethnic Studies Department. Together, they began combing over old sources for any passing reference to Ball and her work. They came to believe that her absence from the scientific record owed to sexism and racism:

During and just after her lifetime, she was believed to be part Hawaiian, not Black. (Her birth and death certificates list both Ball and her parents as white, perhaps to “make travel, business and life in general easier,” according to the Honolulu Star-Bulletin.) In 1910, Black people made up just 0.4 percent of Hawaiʻi’s population.

“When [the newspapers] realized she was not part Hawaiian, but [Black], they felt they had made an embarrassing mistake, forgetting about it and hoping it would go away,” Ali said. “It did for 75 years.”

Their combined efforts spurred the state of Hawaii to declare February 28 Alice Ball Day. The University of Hawaii installed a commemorative plaque near a chaulmoogra tree on campus. Her portrait hangs in the university’s Hamilton Library, alongside a posthumously awarded Medal of Distinction.

(“Meanwhile,” as Carlyn L. Tani dryly observes in Honolulu Magazine, “Dean Hall on the University of Hawai‘i Mānoa campus stands as an enduring monument to Arthur L. Dean.)

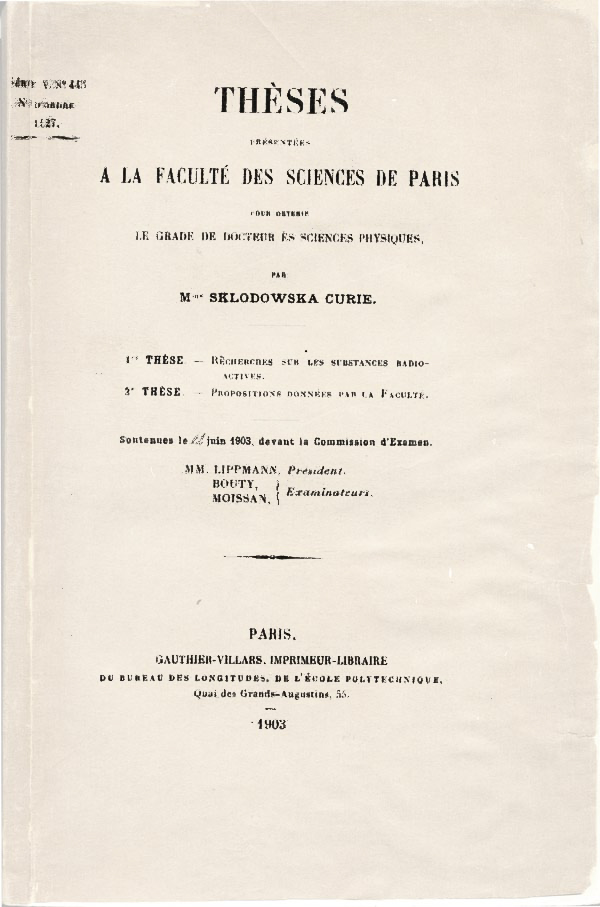

Further afield, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine celebrated its 120th anniversary by adding Ball’s, Marie Sklodowska-Curie’s and Florence Nightingale’s names to a frieze that had previously honored 23 eminent men.

And now, the Godmother of Punk Patti Smith has taken it upon herself to introduce Ball to an even wider audience, after running across a reference to her while conducting research for her just released A Book of Days.

As Smith notes in an interview with Numéro:

Things have really changed. I think we are living in a very beautiful period of time because there are so many female artists, poets, scientists, and activists. Through books especially, we are rediscovering and valuing the women who have been unjustly forgotten in our history. During my research, I came across a young black scientist who lived in Hawaii in the 1920s. At that time, there was a big leper colony in Hawaii. She had discovered a treatment using the oil from the seeds of a tree to relieve the pain and allow patients to see their friends and family. Her name was Alice Ball, and she died at just 24 after a terrible chemical accident during an experiment. Her research was taken up by a professor who removed her name from the study to take full credit. It is only recently that people have discovered that she was the one who did the work.

Related Content

Jocelyn Bell Burnell Changed Astronomy Forever; Her Ph.D. Advisor Won the Nobel Prize for It

How the Female Scientist Who Discovered the Greenhouse Gas Effect Was Forgotten by History

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.