Perhaps, this past Valentine’s Day, you caught a screening of James Cameron’s Titanic, that nineteen-nineties blockbuster having been re-released for its 25th anniversary. You may have even found yourself feeling a renewed appreciation for the film’s precision-engineered mixture of Hollywood romance and technologically robust historical re-creation. As Cameron himself tells it, he and his collaborators were galvanized to reach such heights by making a series of underwater expeditions to see the wreckage of the RMS Titanic itself firsthand in 1995 — less than a decade after that most notorious of all ocean liners was rediscovered.

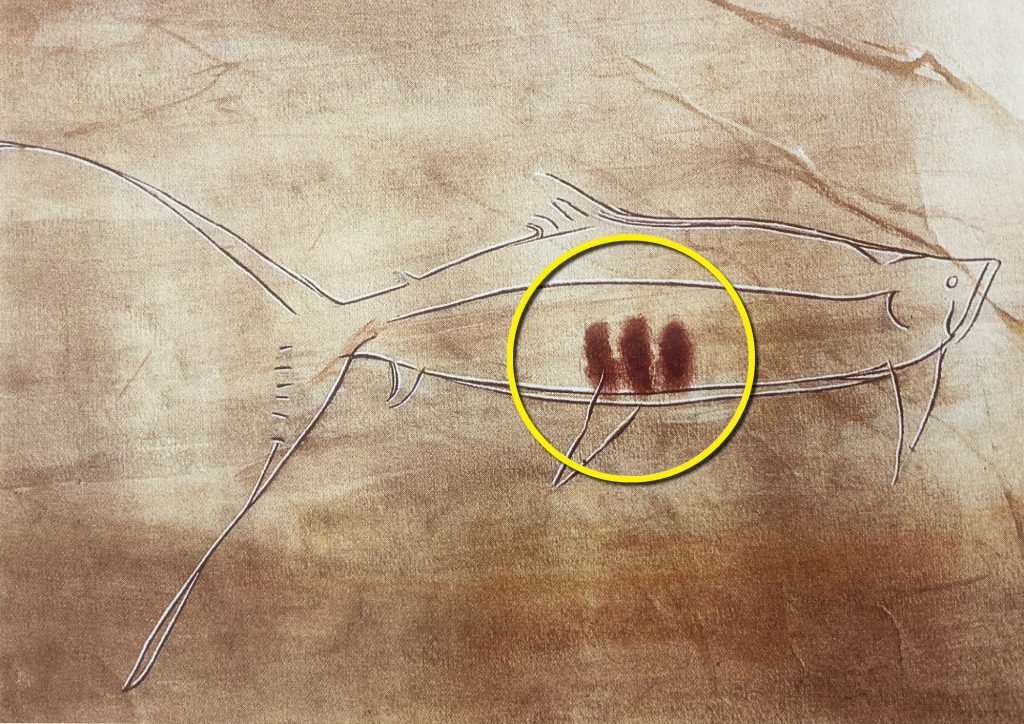

The Titanic vanished beneath the waves of the Atlantic Ocean on April 15, 1912. For nearly 75 years thereafter, nobody saw it again, or indeed had a clear idea of where it even was. It wasn’t until 1985 that its location was determined, thanks to a joint expedition by Jean-Louis Michel of French national oceanographic agency IFREMER and Robert Ballard of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. The job necessitated the use of IFREMER’s new high-resolution sonar as well as the WHOI’s remotely controlled deep-sea vehicle Argo and its companion robot Jason, designed to take pictures and gather objects from the sea floor.

When Ballard and his crew returned to the Titanic the following year, they brought a new cast of machines with them: the deep-diving submersible DSV Alvin, the Jason’s descendant Jason Jr., and the camera system ANGUS (Acoustically Navigated Geological Underwater Survey). You can see more than 80 minutes of the footage they collected in the video at the top of the post, newly uploaded to the WHOI’s Youtube channel. This expedition marked “the first time humans set eyes on the ill-fated ship since 1912,” and most of the footage shot on it has never before been released to the public.

The video offers close-up views of the Titanic’s “rust-caked bow, intact railings, a chief officer’s cabin and a promenade window,” as NPR’s Emily Olson writes. “At one point, the camera zeroes in on a chandelier, still hanging, swaying against the current in a haunting state of elegant decay.” What’s more, “the WHOI’s newly released footage shows the shipwreck in the most complete state we’ll ever see.” Over the past 37 years, the handiwork of the world of undersea organisms have taken their toll on the Titanic, whose remains could vanish almost entirely in a manner of decades — but whose power to inspire works of art will surely go on and on.

Related content:

See the First 8K Footage of the Titanic, the Highest-Quality Video of the Shipwreck Yet

Watch the Titanic Sink in This Real-Time 3D Animation

Titanic Survivor Interviews: What It Was Like to Flee the Sinking Luxury Liner

The Titanic: Rare Footage of the Ship Before Disaster Strikes (1911–1912)

How the Titanic Sank: James Cameron’s New CGI Animation

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.