Sylvia Plath was a study in contrasts. Her popularization as a confessional poet, feminist literary icon, and tragic casualty of major depression; her middle-class Boston background and tortured marriage to poet Ted Hughes—these are the highlights of her biography, and, in many cases, all many people get to know about her. But “she was much more than that,” Dorothy Moss tells Mental Floss. As Vanessa Willoughby puts it in a stunning essay about her own encounters with Plath’s work, “this woman was not the sum of a gas oven and two sleeping children nestled in their beds.”

Moss, a curator at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery has organized an exhibit featuring many more sides of the poet’s divided, yet purposeful self, including her work as a visual artist. Readers of Plath’s poetry may not be surprised to learn she first intended to become an artist. Her visual sense is so keen that fully-formed images seem to leap out of poems like “Blackberrying,” and into the reader’s hands; like the “high green meadows” she describes, her lines are “lit from within” by a deep appreciation for color, texture, and perspective.

Blackberries / Big as the ball of my thumb, and dumb as eyes / Ebon in the hedges, fat / With blue-red juices. These they squander on my fingers.

The blackberries come alive not only in their personification but through the kind of vivid language that could only come from someone with a painterly way of looking at things. Plath “drew and painted and sketched constantly as a child,” says Moss, and first enrolled at Smith College as an art major.

The exhibition, the National Portrait Gallery writes, “reveals how Plath shaped her identity visually as she came of age as a writer in the 1950s.” Unsurprisingly, her most frequent subject is herself. Her visual art, like her poetry, notes Mental Floss, “is often preoccupied with themes of self-identity.” But as in her eloquently-written letters and journals, as well as her published literary work, she is never one self, but many—and not all of them variations on the sly, yet brooding intellectual we see staring out at us from the well-known photographs.

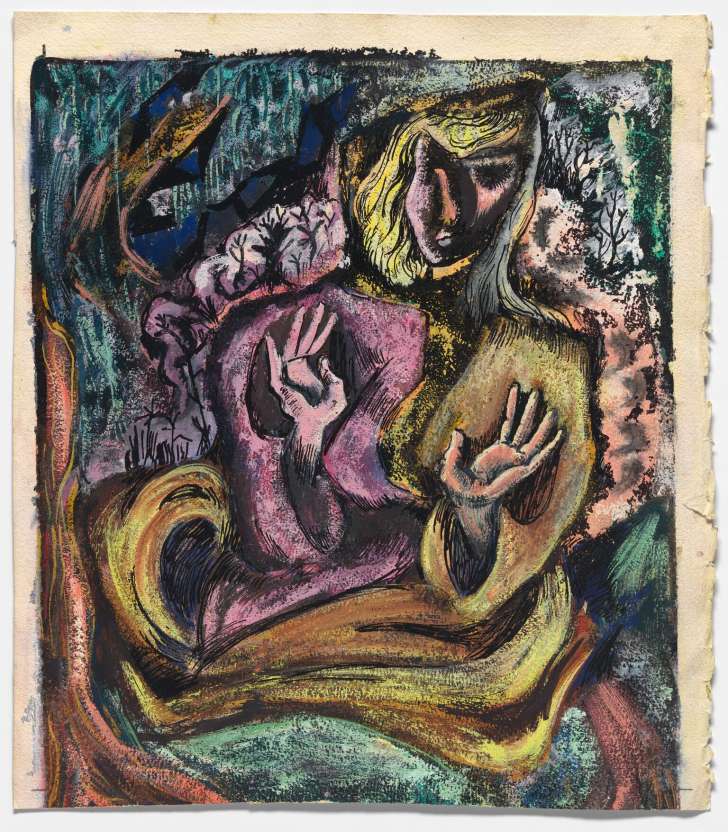

We’ve previously featured some of Plath’s drawings and self-portraits here, but the Smithsonian exhibit offers a considerably richer selection than has been available online. The ink and gouache portrait at the top, for example, seems to draw from Marc Chagall in its materials and swirling lines and colors. It also recalls language in a diary entry from 1953:

Look at that ugly dead mask here and do not forget it. It is a chalk mask with dead dry poison behind it, like the death angel. It is what I was this fall, and what I never want to be again.

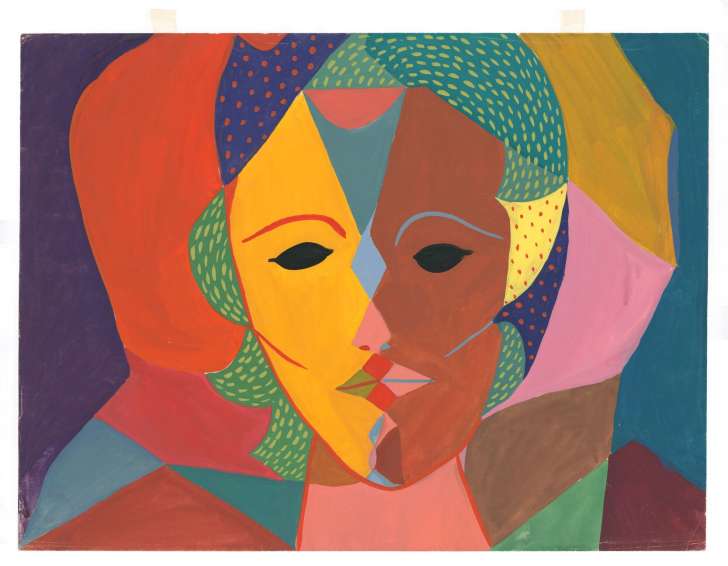

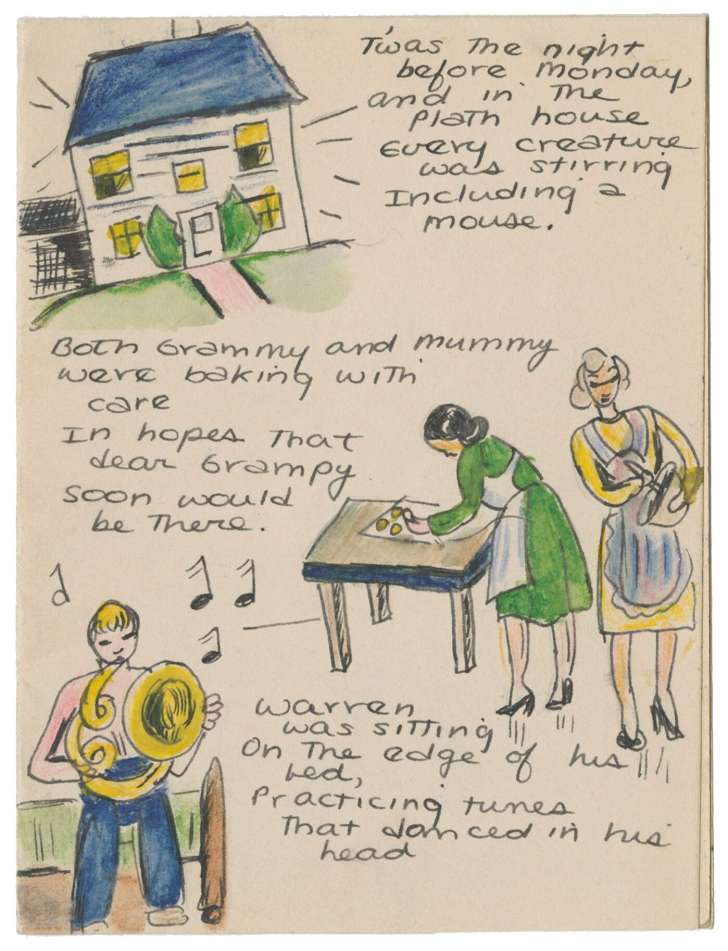

The hands thrown up in defense or surrender, the black lifeless eyes… Plath emerges from the ring of dead trees behind her like a suffering saint. Another portrait, further up also resembles a mask, calling to mind the ancient origins of the word persona. But the style has totally changed, the tumult of brushstrokes smoothed out into clean geometric lines and uniform patches of color. Three masks combine into one face, a trinity of Plaths. The poet always had a sense of herself as divided, referring to two distinct personalities as her “brown-haired” and “platinum” selves. The brown-haired young girl made several charming sketches of her family, with humorous commentary. (Her troubling father is tellingly, perhaps, absent.)

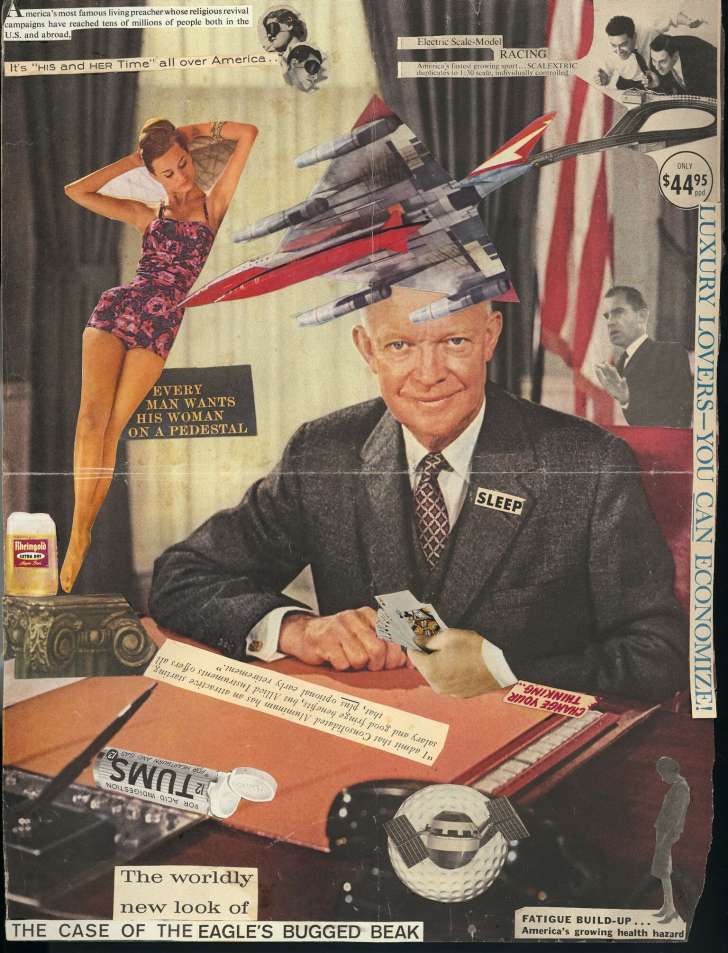

Hers was an epitome of standard-issue 50s white, middle class American childhood, the kind of supposedly idyllic upbringing which no small number of people still remember today in a glowing, nostalgic haze. In Plath’s excavations of the identities that she cultivated herself and those she had pushed upon her, she gazed with radical intensity at America’s patriarchal social fictions, and the violence and entitlement that lay beneath them. The collage above from 1960 presents us with the kind of layered, cut-up, hybrid text that William Burroughs had begun experimenting with not long before. You can see more highlights from the Plath exhibit, “One Life: Sylvia Plath,” at the National Portrait Gallery. Also featured are Plath’s family photos, books, letters, her typewriter—and, in general, several more dimensions of her life than most of us know.

“One Life: Sylvia Plath” runs from June 30, 2017 through May 20, 2018.

Related Content:

The Art of Sylvia Plath: Revisit Her Sketches, Self-Portraits, Drawings & Illustrated Letters

Hear Sylvia Plath Read 15 Poems From Her Final Collection, Ariel, in 1962 Recording

Sylvia Plath’s 10 Back to School Commandments (1953)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply