The Dance Theatre of Harlem Dances Through the Streets of NYC: A Sight to Behold

It’s nearly impossible to find an unblemished square of pavement in New York City.

Unless the concrete was poured within the last day or two, count on each square to boast at least one dark polka dot, an echo of casually discarded gum.

Confirm for yourself with a quick peek beneath the exuberant feet of the Dance Theatre of Harlem company members performing on the plaza of the Adam Clayton Powell Jr. State Office Building during the 46th annual Harlem Week festival.

For obvious reasons, this year’s festival took place entirely online, but the Dance Theatre’s offering is a far cry from the gloomy Zoom‑y affair that’s become 2020’s sad norm.

Eight company members, including co-producers Derek Brockington and Alexandra Hutchinson, hit the streets, to be filmed dancing throughout Harlem.

Those who gripe about the discomfort of wearing a mask while exerting themselves should shut their traps until they’ve performed ballet on the platform of the 145th and St. Nicholas Subway Station, where the dancers’ pristine white shoes bring further buoyancy to the proceedings.

The City College of New York—in-state tuition $7,340—provides the Neo-Gothic stage for four ballerinas to perform en pointe.

The Hudson River and the George Washington Bridge serve as backdrop as four young men soar along the promenade in Denny Farrell Riverbank State Park. Their casual outfits are a reminder of how company founder Arthur Mitchell, the New York City Ballet’s first black principal dancer, deliberately relaxed the dress code to accommodate young men who would have resisted tights.

The piece is an excerpt of New Bach, part of the company’s repertoire by resident choreographer and former principal dancer, Robert Garland, described in an earlier New York Times review as “an authoritative and highly imaginative blend of classical vocabulary and funk, laid out in handsome formal patterns in a well-plotted ballet.”

The music is by J.S. Bach.

And in these fractious times, it’s worth noting that only one of the dancers is New York City born and bred. The others hail from Kansas, Texas, Chicago, Louisiana, Delaware, Orange County, and upstate.

The group seizes the opportunity to amplify a much needed public health message—wear a mask!—but it’s also a beautiful tribute to the power of the arts and the vibrant neighborhood where a world-class company was founded in a converted garage at the height of the civil rights movement.

Contribute to Dance Theater of Harlem’s COVID-19 Relief Fund here.

Related Content:

Ballerina Misty Copeland Recreates the Poses of Edgar Degas’ Ballet Dancers

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...Ella Fitzgerald Imitates Louis Armstrong’s Gravelly Voice While Singing “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love, Baby”

Are great artists born, or are they made? Probably a little of both, but I suspect that deep down, even if we don’t like to admit it, we know it’s probably a little more the former. We can become skilled at most anything with dedication and hard work. Talent is another matter—a mysterious combination of qualities we know when we hear but can’t always define. Ella Fitzgerald had it when she first stepped on stage on amateur night at Harlem’s Apollo Theater as a teenager, intending to do a tap dance routine.

She’d only done the performance on a dare, had no formal training outside of singing in church, her bedroom, and the Harlem streets, and she only chose to sing that night because the act before her did a tap dance and stole her thunder.

She blew the audience away—a tough New York crowd not known for being forgiving—and rendered even the boisterous teenagers in the balcony speechless. “Three encores later,” she wrote, “the $25 prize was mine.” Fitzgerald’s golden, three-octave voice, impeccable timing, and improvisational brilliance are not exactly the kinds of things that can be taught.

She didn’t look the part of the typical female jazz singer, at least according to popular perception, writes Holly Gleason at NPR. “A large woman who’d grown up rough,” including time spent in a New York State reformatory, she was rejected by bandleaders even after that first, revelatory performance, and the press frequently referred to her in terms that disparaged her appearance. “Fitzgerald recognized she didn’t possess Billie Holiday’s torchy allure,” Holly Gleason writes, or “Eartha Kitt’s feral sensuality or Carmen McRae’s sex appeal. But that would not stop the woman who took her vocal cues from the horns, as well as from jazz singer Connee Boswell.”

It didn’t stop her from winning a Grammy in the Grammy’s first year, or having a record label, Verve, founded just to put out her music. Ella’s range and pitch-perfect ear meant she could imitate not only the horn section or her favorite singer Boswell but just about anyone else as well, from popular jazz singer Rose Murphy, with her high, cartoonish voice, “chee chee” affectations, and “brrrp” telephone sound effects, to the low, gravelly rasp of Fitzgerald’s longtime duet partner Louis Armstrong. See her do exactly that in the clip at the top, moving effortlessly in “I Can’t Give You Anything but Love, Baby” from her own voice, to Murphy’s, to Armstrong’s in the space of just a few minutes.

Whatever obstacles Fitzgerald faced, her voice seemed to soar above it all. In becoming a global jazz star and “The First Lady of Song,” says jazz writer Will Friedwald, “she showed people that this is music Americans should be proud of.”

via Ben Phillips

Related Content:

Ella Fitzgerald Sings ‘Summertime’ by George Gershwin, Berlin 1968

How Marilyn Monroe Helped Break Ella Fitzgerald Into the Big Time (1955)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

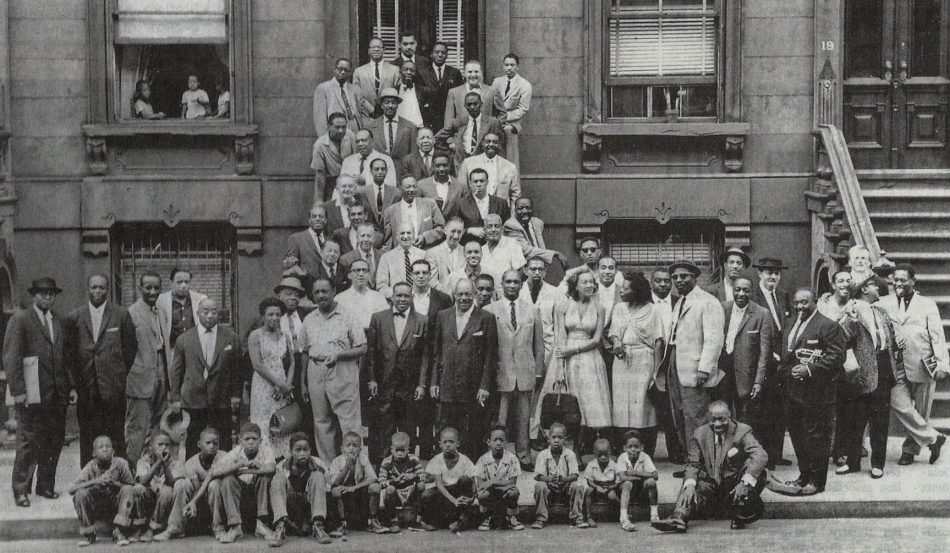

Read More...“A Great Day in Harlem,” Art Kane’s Iconic Photo of 57 Jazz Legends (with a Detailed Listing of Who Appears in the Photo)

Image by Art Kane, via Wikimedia Commons

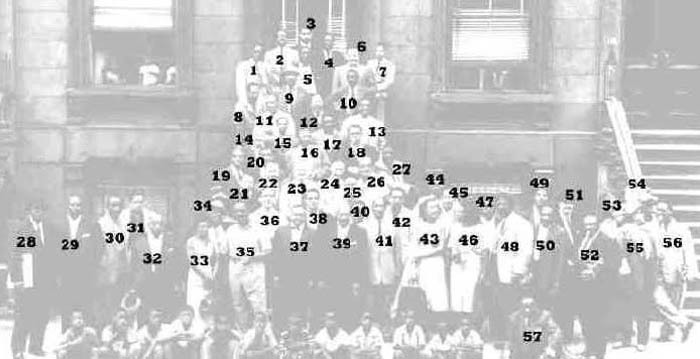

Sixty years ago, Art Kane assembled one of the largest groups of jazz greats in history. No, it wasn’t an all-star big band, but a meeting of veteran legends and young upstarts for the iconic photograph known as “A Great Day in Harlem.” Fifty-seven musicians gathered outside a brownstone at 17 East 126th St.—accompanied by twelve neighborhood kids—from “big rollers,” notes Jazzwise magazine, like “Thelonious Monk, Charles Mingus, Count Basie, Sonny Rollins, Lester Young, Art Blakey, Horace Silver, Dizzy Gillespie, Coleman Hawkins and Pee Wee Russell to then up-and-coming names, Benny Golson, Marion MacPartland, Mary Lou Williams and Art Farmer.”

Sonny Rollins was there, one of only two musicians in the photo still alive. The other, Benny Golson, who turns 90 next year, remembers getting a call from Village Voice critic Nat Hentoff, telling him to get over there. Golson lived in the same building as Quincy Jones, “but somehow he wasn’t called or he didn’t make it.”

Other people who might have been in the photograph but weren’t, Golson says, because they were working (and the 10 a.m. call time was a stretch for a working musician): “John Coltrane, Miles, Duke Ellington, Woody Herman.” And Buddy Rich, whom Golson calls the “greatest drummer I ever heard in my life” (adding, “but his personality was horrible.”)

The next year, everything changed—or so the story goes—when revolutionary albums hit the scene from the likes of Miles Davis, Dave Brubeck, Ornette Coleman, and Charles Mingus. These records pushed experimental forms, leaving behind the confines of both swing and bebop. But Kane’s jazz class photo shows us, Matthew Kessel writes at Vulture, “a portrait of harmony, old and new guard alike peaceably intermingling. The photo suggests that jazz is as much about continuity and tradition as it is about radical change.” The photo has since become a tradition itself, hanging on the walls of thousands of homes, bookshops, record stores, barbershops, and restaurants. (Get your copy here.)

Originally titled “Harlem 1958,” Kane’s image has inspired some notable homages in black culture. In 1998, XXL magazine tapped Gordon Parks to shoot “A Great Day in Hip Hop” for a now-historic cover. And this past summer, Netflix gathered 47 black creatives behind more than 20 original Netflix shows for the redux “A Great Day in Hollywood.” The photo also inspired a documentary of the same title in 1994 (at whose website you can click on each musician for a short bio). At the Daily News, Sarah Goodyear tells the story of how Kane conceived and executed the ambitious project for a special jazz edition of Esquire.

It was his “first professional shooting assignment and, with it, he ended up making history by almost by accident.” Goodyear quotes Kane’s son Jonathan, himself a New York musician, who remarks, “certain things end up being bigger than the original intention. The photograph has become part of our cultural fabric.” For longtime residents of Harlem, the so-called Capital of Black America, and a spiritual home of jazz, it’s just like an old family portrait. See a fully annotated version of “A Great Day in Harlem” at Harlem.org, and at the Daily News, an interactive version with links to YouTube recordings and performances from every one of the 57 musicians in the picture.

This month, to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the photo, Wall of Sound Gallery will publish the book Art Kane: Harlem 1958, a retrospective with outtakes from the photo session and text from Quincy Jones, Benny Golson, Jonathan Kane, and Art himself. “The importance of this photo transcends time and location,” writes Jones in his forward, “leaving it to become not only a symbolic piece of art, but a piece of history. During a time in which segregation was very much still a part of our everyday lives, and in a world that often pointed out our differences instead of celebrating our similarities, there was something so special and pure about gathering 57 individuals together, in the name of jazz.”

- Hilton Jefferson (1903–1968)

- Benny Golson (1929-)

- Art Farmer (1928–2003)

- Wilbur Ware (1923–1979)

- Art Blakey (1919–1990)

- Chubby Jackson (1918–2003)

- Johnny Griffin (1928–2008)

- Dickie Wells (1909–1985)

- Buck Clayton (1911–1993)

- Taft Jordan (1915–1981)

- Zutty Singleton (1898–1975)

- Henry “Red” Allen (1908–1967)

- Tyree Glenn (1912–1972)

- Miff Mole (1898–1961)

- Sonny Greer (1903–1982)

- J.C. Higginbotham (1906–1973)

- Jimmy Jones (1918–1982)

- Charles Mingus (1922–1979)

- Jo Jones (1911–1985)

- Gene Krupa (1909–1973)

- Max Kaminsky (1908–1994)

- George Wettling (1907–1968)

- Bud Freeman (1906–1988)

- Pee Wee Russell (1906–1969)

- Ernie Wilkins (1922–1999)

- Buster Bailey (1902–1967)

- Osie Johnson (1923–1968)

- Gigi Gryce (1927–1983)

- Hank Jones (1918–2010)

- Eddie Locke (1930–2009)

- Horace Silver (1928–2014)

- Luckey Roberts (1887–1968)

- Maxine Sullivan (1911–1987)

- Jimmy Rushing (1902–1972)

- Joes Thomas (1909–1984)

- Scoville Browne (1915–1994)

- Stuff Smith (1909–1967)

- Bill Crump (1919–1980s)

- Coleman Hawkins (1904–1969)

- Rudy Powell (1907–1976)

- Oscar Pettiford (1922–1960)

- Sahib Shihab (1925–1993)

- Marian McPartland (1920–2013)

- Sonny Rollins (1929-)

- Lawrence Brown (1905–1988)

- Mary Lou Williams (1910–1981)

- Emmett Berry (1915–1993)

- Thelonious Monk (1917–1982)

- Vic Dickenson (1906–1984)

- Milt Hinton (1910–2000)

- Lester “Pres” Young (1909–1959)

- Rex Stewart (1907–1972)

- J.C. Heard (1917–1988)

- Gerry Mulligan (1927–1995)

- Roy Eldridge (1911–1989)

- Dizzy Gillespie (1917–1993)

- William “Count” Basie (1904–1984)

Related Content:

1959: The Year That Changed Jazz

Hear 2,000 Recordings of the Most Essential Jazz Songs: A Huge Playlist for Your Jazz Education

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

Read More...Marjorie Eliot Has Held Free Jazz Concerts in Her Harlem Apartment Every Sunday for the Past 25 Years

I spent a good part of a decade-long sojourn through New York City in Harlem—at the neighborhood’s threshold at the top of Central Park, just a short walk from its historic main attractions: jazz haunts, famed restaurants, theaters, architectural splendor and wide, vibrant avenues. After a while, I thought I knew Harlem well enough. Then I moved to Sugar Hill, at the very edge of the island, across the water from Yankee Stadium. Usually overlooked, leafy street after street of stately brownstones and pre-World War I apartment buildings, sometimes worse for wear but always regal. A few avenue blocks from my building: St. Nick’s Pub, which I became convinced, for good reason, was the city’s true remaining heart of jazz.

Shuttered, to the neighborhood’s dismay, in 2012, the humble bar—where, on any given night, Afro-jazz, hard bop, free jazz, and classic swing ensembles of the very finest musicians performed from dusk till dawn, passing the hat to an always appreciative crowd—was, as a New York Times obituary for the deceased nightspot wrote, “simply magical… one of the few remaining jazz clubs in Harlem.” But then, I didn’t visit Marjorie Eliot’s apartment. I remember seeing her play at St. Nick’s a time or two, but never made it over to 555 Edgecombe Avenue, Apartment 3‑F. This was to my great loss.

It’s not too late. Since 1994, Ms. Eliot, a jazz pianist, has carried on a grand tradition of Harlem’s from its golden ages, with weekly house concerts in her parlor, “Harlem’s secret jazz queen of Sugar Hill,” writes Angelika Pokovba, “single-handedly upholding the musical legacy of a neighborhood that nurtured legends like Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday.”

Except she isn’t single-handed, as you can see in the videos here, but always joined by a talented crew of players whom she handpicks and pays out of pocket. The hat is passed, but no one’s obligated to pay, there are no tickets, door charges, or drink minimums; all you’ve got to do is show up at 3:30 on a Sunday afternoon.

Marjorie greets each guest at the door. A full house is a crowd of up to 50 people. The atmosphere is reserved and family friendly, a far cry from the riotous rent parties of legend. But this is the place to be, say both the regulars and the musicians, like saxophonist Cedric Show Croon, who told NPR, “When you play here you have to be honest. You can only play in an honest way, you know.” You can get a small taste of the intimacy here, but to truly experience Parlor Jazz at Marjorie Eliot’s—as a Harlem culture guide notes—you’ve got to travel uptown yourself.

“Rain or shine, with no vacations,” the free concerts have gone on for 25 years now, beginning, as you’ll see in the video above, with a tragedy, the death of Eliot’s son Philip in 1992. The following year, on the anniversary of his death, she arranged an outdoor concert on the lawn of Morris-Jumel Mansion in Washington Heights. Then, the next year, the memorial moved to her apartment and became a weekly gig that carried her through more terrible loss—the death of another son and the disappearance of a third.

Eliot refused to give up on the music that kept her going, creating community in an easygoing, open-hearted way. “This idea of sharing and celebrating the music came real early,” she told NPR. “So I don’t do anything different now than when Aunt Margaret is coming over and come show what you did in your lessons.” As you’ll see in the videos here—and experience in full, no doubt, if you can make the trip: Parlor Jazz at Marjorie Eliot’s is anything but an ordinary Sunday afternoon with Aunt Margaret.

Via Messy Nessy

Related Content:

Women of Jazz: Stream a Playlist of 91 Recordings by Great Female Jazz Musicians

Hear 2,000 Recordings of the Most Essential Jazz Songs: A Huge Playlist for Your Jazz Education

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

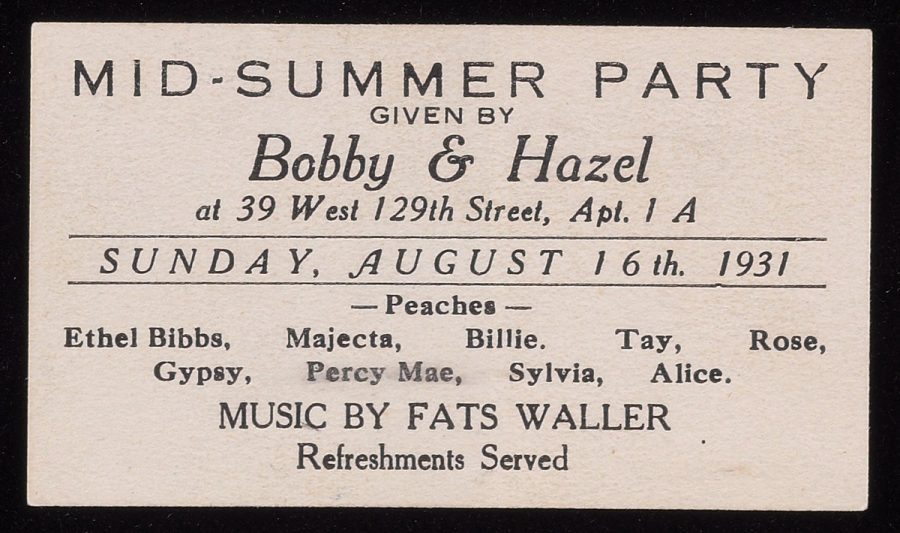

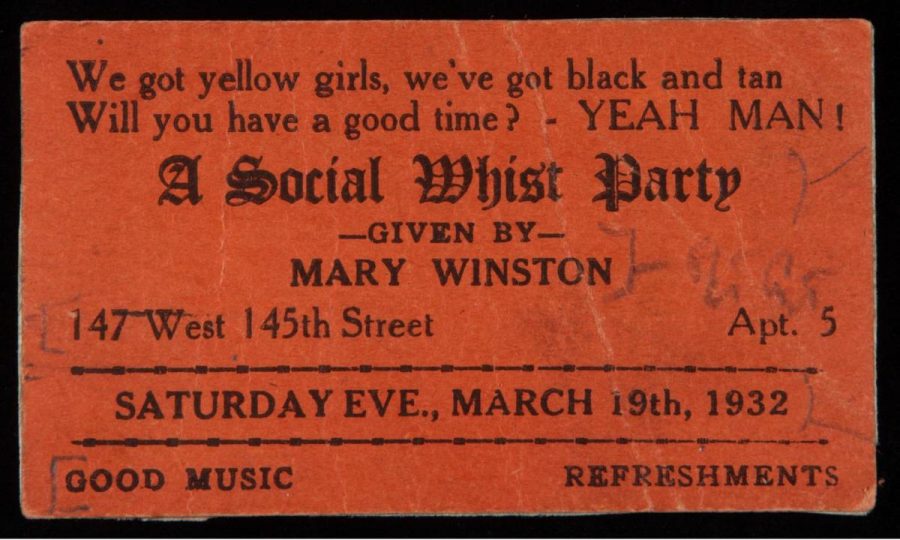

Read More...Discover Langston Hughes’ Rent Party Ads & The Harlem Renaissance Tradition of Playing Gigs to Keep Roofs Over Heads

Both communities of color and communities of artists have had to take care of each other in the U.S., creating systems of support where the dominant culture fosters neglect and deprivation. In the early twentieth century, at the nexus of these two often overlapping communities, we meet Langston Hughes and the artists, poets, and musicians of the Harlem Renaissance. Hughes’ brilliantly compressed 1951 poem “Harlem” speaks of the simmering frustration among a weary people. But while its startling final line hints grimly at social unrest, it also looks back to the explosion of creativity in the storied New York City neighborhood during the Great Depression.

Hughes had grown reflective in the 50s, returning to the origins of jazz and blues and the history of Harlem in Montage of a Dream Deferred. The strained hopes and hardships he had eloquently documented in the 20s and 30s remained largely the same post-World War II, and one of the key features of Depression-era Harlem had returned; Rent parties, the wild shindigs held in private apartments to help their residents avoid eviction, were back in fashion, Hughes wrote in the Chicago Defender in 1957.

“Maybe it is inflation today and the high cost of living that is causing the return of the pay-at-the-door and buy-your-own-refreshments parties,” he said. He also noted that the new parties weren’t as much fun.

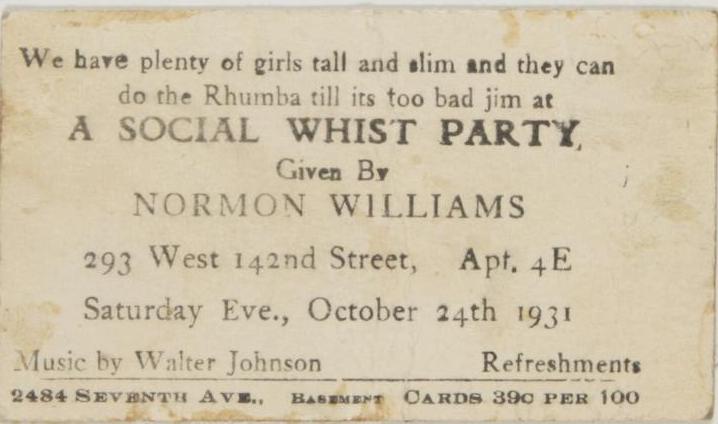

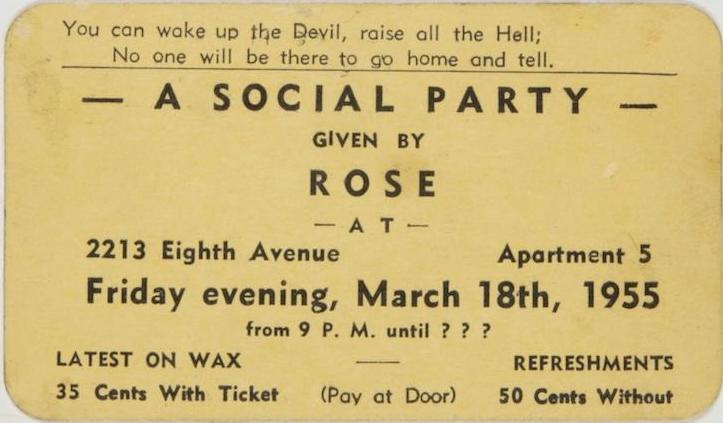

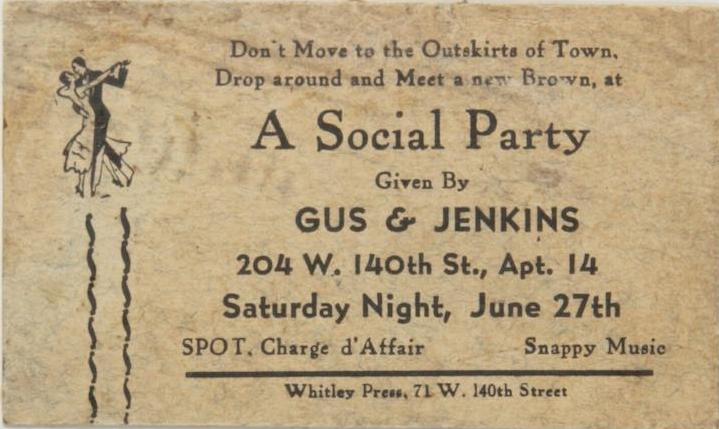

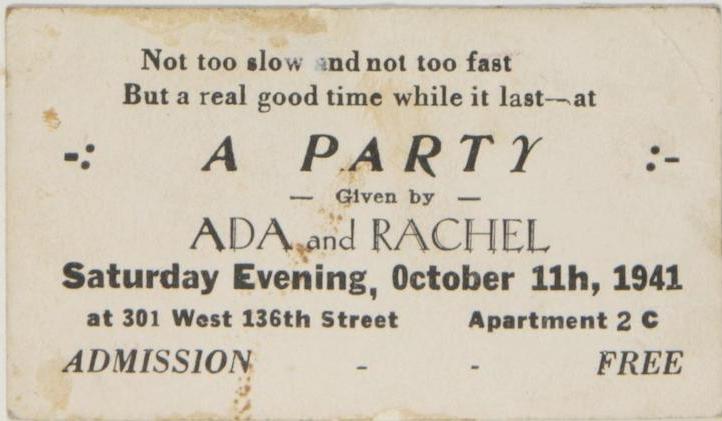

But how could they be? Depression-era rent parties were legendary. They “impacted the growth of Swing and Blues dancing,” writes dance teacher Jered Morin, “like few other periods.” As Hughes commented, “the Saturday night rent parties that I attended were often more amusing than any night club, in small apartments where God-knows-who lived.” Famous artists met and rubbed elbows, musicians formed impromptu jams and invented new styles, working class people who couldn’t afford a night out got to put on their best clothes and cut loose to the latest music. Hughes was fascinated, and as a writer, he was also quite taken by the quirky cards used to advertise the parties. “When I first came to Harlem,” he said, “as a poet I was intrigued by the little rhymes at the top of most House Rent Party cards, so I saved them. Now I have quite a collection.”

The cards you see here come from Hughes’ personal collection, held with his papers at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Many of these date from the 40s and 50s, but they all draw their inspiration from the Harlem Renaissance period, when the phenomenon of jazz-infused rent parties exploded. “Sandra L. West points out that black tenants in Harlem during the 1920s and 1930s faced discriminatory rental rates,” notes Rebecca Onion at Slate. “That, along with the generally lower salaries for black workers, created a situation in which many people were short of rent money. These parties were originally meant to bridge that gap.” A 1938 Federal Writers Project account put it plainly: Harlem “was a typical slum and tenement area little different from many others in New York except for the fact that in Harlem rents were higher; always have been, in fact, since the great war-time migratory influx of colored labor.”

Tenants took it in stride, drawing on two longstanding community traditions to make ends meet: the church fundraiser and the Saturday night fish fry. But rent parties could be raucous affairs. Guests typically paid a few cents to enter, and extra for food cooked by the host. Apartments filled far beyond capacity, and alcohol—illegal from 1919 to 1933—flowed freely. Gambling and prostitution frequently made an appearance. And the competition could be fierce. The Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance writes that in their heyday, “as many as twelve parties in a single block and five in an apartment building, simultaneously, were not uncommon.” Rent parties “essentially amounted to a kind of grassroots social welfare,” though the atmosphere could be “far more sordid than the average neighborhood block party.” Many upright citizens who disapproved of jazz, gambling, and booze turned up their noses and tried to ignore the parties.

In order to entice party-goers and distinguish themselves, writes Onion, “the cards name the kind of musical entertainment attendees could expect using lyrics from popular songs or made-up rhyming verse as slogans.” They also “used euphemisms to name the parties’ purpose,” calling them “Social Whist Party” or “Social Party,” while also slyly hinting at rowdier entertainments. The new rent parties may not have lived up to Hughes’ memories of jazz-age shindigs, perhaps because, in some cases, live musicians had been replaced by record players. But the new cards, he wrote “are just as amusing as the old ones.”

Related Content:

Langston Hughes Presents the History of Jazz in an Illustrated Children’s Book (1955)

Watch Langston Hughes Read Poetry from His First Collection, The Weary Blues (1958)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...The Harlem Jazz Singer Who Inspired Betty Boop: Meet the Original Boop-Oop-a-Doop, “Baby Esther”

Jazz Age cartoon flapper, Betty Boop, inhabits that rare pantheon of stars whose fame has not dimmed with time.

While she was never alive per se, her ten year span of active film work places her somewhere between James Dean and Marilyn Monroe. The market for Boop-collectibles is so vast, a definitive guide was published in 2003. Most recently, Betty has popped up on prepaid debit cards and emoji, and inspired fashion’s enfant terrible Jean Paul Gaultier to create a fragrance in her honor.

As noted in the brief history in the video above, Betty hailed from animator Max Fleischer’s Fleischer Studios and actress Margie Hines provided her voice.

Physically, she bore a close resemblance to popular singer Helen Kane. Their babyish vocal stylings were remarkably similar, too. But when Betty put the bite on a couple of Kane’s hits, below, Kane fought back with a lawsuit against Paramount and Max Fleischer Studios, seeking damages and an injunction which would have prevented them from making more Betty Boop cartoons.

The Associated Press reported that Kane confounded the court stenographer who had no idea how to spell the Boopsian utterances she reproduced before the judge, in an effort to establish ownership. Her case seemed pretty solid until the defense called Lou Bolton, a theatrical manager whose client roster had once included Harlem jazz singer,“Baby Esther” Jones.

Two years before Betty Boop debuted (as an anthropomorphic poodle) in the cartoon short, Dizzy Dishes, above, Kane and her manager took in Baby Esther’s act in New York. A couple of weeks’ later the nonsensical interjections that were part of Baby Esther’s schtick, below, began creeping into Kane’s performances.

According to the Associated Press, Bolton testified that:

Baby Esther made funny expressions and interpolated meaningless sounds at the end of each bar of music in her songs.

“What sounds did she interpolate?” asked Louis Phillips, a defense attorney.

“Boo-Boo-Boo!” recited Bolton.

“What other sounds?”

“Doo-Doo-Doo!”

“Any others?”

“Yes, Wha-Da-Da-Da!”

Baby Esther herself did not attend the trial, and did not much benefit from Kane’s loss. Casual cartoon historians are far more likely to identify Kane as the inspiration for the animated Boop-oop-a-doop girl. You can hear Kane on cds and Spotify, but you won’t find Baby Esther.

With a bit more digging, however, you will find Gertrude Saunders — the given name of “Baby Esther” — belting it out on Spotify. Some of her intonations are a bit reminiscent of Bessie Smith… who hated her (not without reason). Saunders appeared in a few movies and died in 1991.

Related Content:

Free Vintage Cartoons: Bugs Bunny, Betty Boop and More

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Her play Zamboni Godot is opening in New York City in March 2017. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...1944 Instructional Video Teaches You the Lindy Hop, the Dance That Originated in 1920’s Harlem Ballrooms

1944’s MGM short Groovie Movie, above, bills itself as an instructional film for those wishing to learn the Lindy Hop and its extremely close cousin, the Jitterbug.

The educational model here is definitely of the “toss ‘em in the pool and see if they swim” variety.

The easily frustrated are advised to seek out a calm and patient teacher, willing to break the footwork down into a number of small, easily digestible lessons.

Or better yet, find someone to teach you in person. We’re about 20 years into a swing dance revival, and with a bit of Googling, you should be able to find an athletic young teacher who can school you in the dance popularized by Frankie “Musclehead” Manning and his partner Freda Washington at Harlem’s Savoy ballroom.

Speaking of teachers, you might recognize Arthur “King Cat” Walsh, the “top flight hep cat” star of Groovie Movie, as the fellow who was brought in to teach I Love Lucy’s Lucy Ricardo how to boogie woogie.

He’s got more chemistry with his Groovie Movie partner, Jean Veloz. Backed by Lenny Smith, Kay Vaughn, Irene Thomas, Chuck Saggau, and several talented kiddies, they quickly achieve an astonishingly manic intensity as narrator Pete Smith barks out a host of jazzy lingo. (Herein, lays the truly solid instruction. The attitude!)

Smith also heps viewers to a few of the influences at work, including ballet, traditional Javanese dance, and even the “gay old waltz.” Sadly, he fails to mention the Harlem ballroom scene from whence it most directly sprung.

At least Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers, a professional troop drawn from the Savoy’s most skilled practitioners, got their due in the 1941 film, Hellzapoppin’, below. Again, astonishing!

Okay, worms, let’s squirm.

Related Content:

James Brown Gives You Dancing Lessons: From The Funky Chicken to The Boogaloo

Jazz ‘Hot’: The Rare 1938 Short Film With Jazz Legend Django Reinhardt

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Her play Zamboni Godot is opening in New York City in March 2017. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...A 103-Year-Old Harlem Renaissance Dancer Sees Herself on Film for the First Time & Becomes an Internet Star

The Harlem Renaissance lives in the form of Alice Barker, a soft spoken lady who just last week received a belated Happy 103rd Birthday card from the Obamas.

That’s her on the right in the first clip, below. She’s in the back right at the 2:07 mark. Perched on a lunch counter stool, showing off her shapely stems at 9:32.

Barker’s newfound celebrity is an unexpected reward for one who was never a marquee name.

She was a member of the chorus—a pretty, talented, hardworking young lady, whose name was misspelled on one of the occasions when she was credited. She danced throughout the 1930s and 40s in legendary Harlem venues like the Apollo, the Cotton Club, and the Zanzibar Club. Shared the stage with Frank Sinatra, Gene Kelly, and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. Racked up a number of film, commercial and TV credits, getting paid to do something she later confided from a nursing home bed she would have gladly done for free.

Barker’s chorus girl days had been mothballed for decades when she crossed paths with video editor David Shuff, a volunteer visitor to the nursing home where she lives. Shuff seems to be a kindred spirit to the writer David Greenberger, whose Duplex Planet zines—and later books, comics, and performances—captured the stories (and personalities) of the elderly residents of a Boston nursing home where he served as activities director.

Intrigued by glimmers of Barker’s glamorous past, Shuff joined forces with recreational therapist Gail Campbell, to see if they could truffle up any evidence. Barker herself had lost all of the photos and memorabilia that would have backed up her claims.

Eventually, their search led them to historians Alicia Thompson and Mark Cantor, who were able to identify Barker strutting her stuff in a handful of extant 1940s jukebox shorts, aka “soundies.”

Though Barker had caught herself in a couple of commercials, she had never seen any of her soundie performances. A friend of Shuff’s serendipitously decided to record her reaction to her first private screening on Shuff’s iPad. The video went viral as soon as it hit the Internet, and suddenly, Barker was a star.

The loveliest aspect of her late-in-life celebrity is an abundance of old fashioned fan mail, flowers and artwork. She also received a Jimmie Lunceford Legacy Award for excellence in music and music education.

Fame is heady, but seems not to have gone to Barker’s, as evidenced by a remark she made to Shuff a couple of months after she blew up the Internet, “I got jobs because I had great legs, but also, I knew how to wink.”

Shuff maintains a website for fans who want to stay abreast of Alice Barker. You can also write her at the address below:

Alice Barker

c/o Brooklyn Gardens

835 Herkimer Street

Brooklyn, NY11233

Related Content:

A 1932 Illustrated Map of Harlem’s Night Clubs: From the Cotton Club to the Savoy Ballroom

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Her play, Fawnbook, is running through November 20 in New York City. Follow her @AyunHalliday

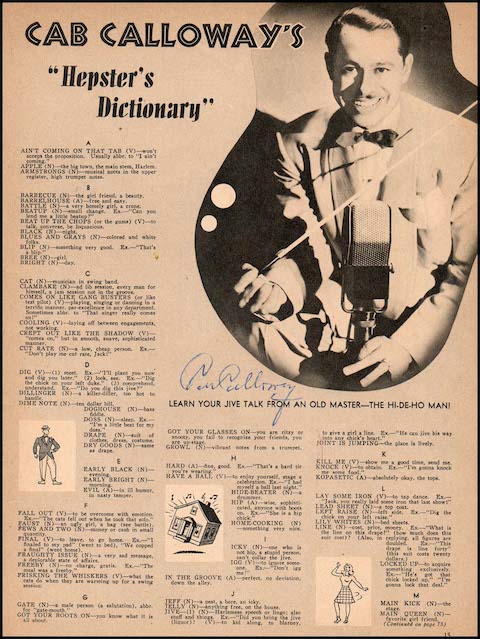

Read More...Cab Calloway’s “Hepster Dictionary,” a 1939 Glossary of the Lingo (the “Jive”) of the Harlem Renaissance

The lists are in. By overwhelming consensus, the buzzword of 2014 was “vape.” Apparently, that’s the verb that enables you to smoke an e‑cig. Left to its own devices, my computer will still autocorrect 2014’s biggest word to “cape,” but that could change.

Hopefully not.

Hopefully, 2015 will yield a buzzword more piquant than “vape.”

With luck, a razor-witted teen is already on the case, but just in case, let’s hedge our bets. Let’s go spelunking in an era when buzzwords were cool, but adult…insouciant, yet substantive.

Lead us, Cab Calloway!

The charismatic bandleader not only had a way with words, his love of them led him to compile a “Hepster’s Dictionary” of Harlem musician slang circa 1938. It featured 200 expressions used by the “hep cats” when they talk their “jive” in the clubs on Lenox Avenue. It was also apparently the first dictionary authored by an African-American.

If only every amateur lexicographer were foxy enough to set his or her definitions to music, and creep them out like the shadow, as Calloway does above. The complete list is below.

What a blip!

By my calculation, we’ve got eleven months to identify a choice candidate, resurrect it, and integrate it into everyday speech. With luck some fine dinner whose star is on the rise will beef our word in public, preferably during a scandalous, much analyzed performance.

It’s immaterial which one we pick. Gammin’? Jeff? Hincty? Fruiting? Whatever you choose, I’m in. Let’s blow their wigs.

Bust your conks in the comments section. I’m ready.

HEPSTER’S DICTIONARY

A hummer (n.) — exceptionally good. Ex., “Man, that boy is a hummer.”

Ain’t coming on that tab (v.) — won’t accept the proposition. Usually abbr. to “I ain’t coming.”

Alligator (n.) — jitterbug.

Apple (n.) — the big town, the main stem, Harlem.

Armstrongs (n.) — musical notes in the upper register, high trumpet notes.

Barbecue (n.) — the girl friend, a beauty

Barrelhouse (adj.) — free and easy.

Battle (n.) — a very homely girl, a crone.

Beat (adj.) — (1) tired, exhausted. Ex., “You look beat” or “I feel beat.” (2) lacking anything. Ex, “I am beat for my cash”, “I am beat to my socks” (lacking everything).

Beat it out (v.) — play it hot, emphasize the rhythym.

Beat up (adj.) — sad, uncomplimentary, tired.

Beat up the chops (or the gums) (v.) — to talk, converse, be loquacious.

Beef (v.) — to say, to state. Ex., “He beefed to me that, etc.”

Bible (n.) — the gospel truth. Ex., “It’s the bible!”

Black (n.) — night.

Black and tan (n.) — dark and light colored folks. Not colored and white folks as erroneously assumed.

Blew their wigs (adj.) — excited with enthusiasm, gone crazy.

Blip (n.) — something very good. Ex., “That’s a blip”; “She’s a blip.”

Blow the top (v.) — to be overcome with emotion (delight). Ex., “You’ll blow your top when you hear this one.”

Boogie-woogie (n.) — harmony with accented bass.

Boot (v.) — to give. Ex., “Boot me that glove.”

Break it up (v.) — to win applause, to stop the show.

Bree (n.) — girl.

Bright (n.) — day.

Brightnin’ (n.) — daybreak.

Bring down ((1) n. (2) v.) — (1) something depressing. Ex., “That’s a bring down.” (2) Ex., “That brings me down.”

Buddy ghee (n.) — fellow.

Bust your conk (v.) — apply yourself diligently, break your neck.

Canary (n.) — girl vocalist.

Capped (v.) — outdone, surpassed.

Cat (n.) — musician in swing band.

Chick (n.) — girl.

Chime (n.) — hour. Ex., “I got in at six chimes.”

Clambake (n.) — ad lib session, every man for himself, a jam session not in the groove.

Chirp (n.) — female singer.

Cogs (n.) — sun glasses.

Collar (v.) — to get, to obtain, to comprehend. Ex., “I gotta collar me some food”; “Do you collar this jive?”

Come again (v.) — try it over, do better than you are doing, I don’t understand you.

Comes on like gangbusters (or like test pilot) (v.) — plays, sings, or dances in a terrific manner, par excellence in any department. Sometimes abbr. to “That singer really comes on!”

Cop (v.) — to get, to obtain (see collar; knock).

Corny (adj.) — old-fashioned, stale.

Creeps out like the shadow (v.) — “comes on,” but in smooth, suave, sophisticated manner.

Crumb crushers (n.) — teeth.

Cubby (n.) — room, flat, home.

Cups (n.) — sleep. Ex., “I gotta catch some cups.”

Cut out (v.) — to leave, to depart. Ex., “It’s time to cut out”; “I cut out from the joint in early bright.”

Cut rate (n.) — a low, cheap person. Ex., “Don’t play me cut rate, Jack!”

Dicty (adj.) — high-class, nifty, smart.

Dig (v.) — (1) meet. Ex., “I’ll plant you now and dig you later.” (2) look, see. Ex., “Dig the chick on your left duke.” (3) comprehend, understand. Ex., “Do you dig this jive?”

Dim (n.) — evening.

Dime note (n.) — ten-dollar bill.

Doghouse (n.) — bass fiddle.

Domi (n.) — ordinary place to live in. Ex., “I live in a righteous dome.”

Doss (n.) — sleep. Ex., “I’m a little beat for my doss.”

Down with it (adj.) — through with it.

Drape (n.) — suit of clothes, dress, costume.

Dreamers (n.) — bed covers, blankets.

Dry-goods (n.) — same as drape.

Duke (n.) — hand, mitt.

Dutchess (n.) — girl.

Early black (n.) — evening

Early bright (n.) — morning.

Evil (adj.) — in ill humor, in a nasty temper.

Fall out (v.) — to be overcome with emotion. Ex., “The cats fell out when he took that solo.”

Fews and two (n.) — money or cash in small quatity.

Final (v.) — to leave, to go home. Ex., “I finaled to my pad” (went to bed); “We copped a final” (went home).

Fine dinner (n.) — a good-looking girl.

Focus (v.) — to look, to see.

Foxy (v.) — shrewd.

Frame (n.) — the body.

Fraughty issue (n.) — a very sad message, a deplorable state of affairs.

Freeby (n.) — no charge, gratis. Ex., “The meal was a freeby.”

Frisking the whiskers (v.) — what the cats do when they are warming up for a swing session.

Frolic pad (n.) — place of entertainment, theater, nightclub.

Fromby (adj.) — a frompy queen is a battle or faust.

Front (n.) — a suit of clothes.

Fruiting (v.) — fickle, fooling around with no particular object.

Fry (v.) — to go to get hair straightened.

Gabriels (n.) — trumpet players.

Gammin’ (adj.) — showing off, flirtatious.

Gasser (n, adj.) — sensational. Ex., “When it comes to dancing, she’s a gasser.”

Gate (n.) — a male person (a salutation), abbr. for “gate-mouth.”

Get in there (exclamation.) — go to work, get busy, make it hot, give all you’ve got.

Gimme some skin (v.) — shake hands.

Glims (n.) — the eyes.

Got your boots on — you know what it is all about, you are a hep cat, you are wise.

Got your glasses on — you are ritzy or snooty, you fail to recognize your friends, you are up-stage.

Gravy (n.) — profits.

Grease (v.) — to eat.

Groovy (adj.) — fine. Ex., “I feel groovy.”

Ground grippers (n.) — new shoes.

Growl (n.) — vibrant notes from a trumpet.

Gut-bucket (adj.) — low-down music.

Guzzlin’ foam (v.) — drinking beer.

Hard (adj.) — fine, good. Ex., “That’s a hard tie you’re wearing.”

Hard spiel (n.) — interesting line of talk.

Have a ball (v.) — to enjoy yourself, stage a celebration. Ex., “I had myself a ball last night.”

Hep cat (n.) — a guy who knows all the answers, understands jive.

Hide-beater (n.) — a drummer (see skin-beater).

Hincty (adj.) — conceited, snooty.

Hip (adj.) — wise, sophisticated, anyone with boots on. Ex., “She’s a hip chick.”

Home-cooking (n.) — something very dinner (see fine dinner).

Hot (adj.) — musically torrid; before swing, tunes were hot or bands were hot.

Hype (n, v.) — build up for a loan, wooing a girl, persuasive talk.

Icky (n.) — one who is not hip, a stupid person, can’t collar the jive.

Igg (v.) — to ignore someone. Ex., “Don’t igg me!)

In the groove (adj.) — perfect, no deviation, down the alley.

Jack (n.) — name for all male friends (see gate; pops).

Jam ((1)n, (2)v.) — (1) improvised swing music. Ex., “That’s swell jam.” (2) to play such music. Ex., “That cat surely can jam.”

Jeff (n.) — a pest, a bore, an icky.

Jelly (n.) — anything free, on the house.

Jitterbug (n.) — a swing fan.

Jive (n.) — Harlemese speech.

Joint is jumping — the place is lively, the club is leaping with fun.

Jumped in port (v.) — arrived in town.

Kick (n.) — a pocket. Ex., “I’ve got five bucks in my kick.”

Kill me (v.) — show me a good time, send me.

Killer-diller (n.) — a great thrill.

Knock (v.) — give. Ex., “Knock me a kiss.”

Kopasetic (adj.) — absolutely okay, the tops.

Lamp (v.) — to see, to look at.

Land o’darkness (n.) — Harlem.

Lane (n.) — a male, usually a nonprofessional.

Latch on (v.) — grab, take hold, get wise to.

Lay some iron (v.) — to tap dance. Ex., “Jack, you really laid some iron that last show!”

Lay your racket (v.) — to jive, to sell an idea, to promote a proposition.

Lead sheet (n.) — a topcoat.

Left raise (n.) — left side. Ex., “Dig the chick on your left raise.”

Licking the chops (v.) — see frisking the whiskers.

Licks (n.) — hot musical phrases.

Lily whites (n.) — bed sheets.

Line (n.) — cost, price, money. Ex., “What is the line on this drape” (how much does this suit cost)? “Have you got the line in the mouse” (do you have the cash in your pocket)? Also, in replying, all figures are doubled. Ex., “This drape is line forty” (this suit costs twenty dollars).

Lock up — to acquire something exclusively. Ex., “He’s got that chick locked up”; “I’m gonna lock up that deal.”

Main kick (n.) — the stage.

Main on the hitch (n.) — husband.

Main queen (n.) — favorite girl friend, sweetheart.

Man in gray (n.) — the postman.

Mash me a fin (command.) — Give me $5.

Mellow (adj.) — all right, fine. Ex., “That’s mellow, Jack.”

Melted out (adj.) — broke.

Mess (n.) — something good. Ex., “That last drink was a mess.”

Meter (n.) — quarter, twenty-five cents.

Mezz (n.) — anything supreme, genuine. Ex., “this is really the mezz.”

Mitt pounding (n.) — applause.

Moo juice (n.) — milk.

Mouse (n.) — pocket. Ex., “I’ve got a meter in the mouse.”

Muggin’ (v.) — making ‘em laugh, putting on the jive. “Muggin’ lightly,” light staccato swing; “muggin’ heavy,” heavy staccato swing.

Murder (n.) — something excellent or terrific. Ex., “That’s solid murder, gate!”

Neigho, pops — Nothing doing, pal.

Nicklette (n.) — automatic phonograph, music box.

Nickel note (n.) — five-dollar bill.

Nix out (v.) — to eliminate, get rid of. Ex., “I nixed that chick out last week”; “I nixed my garments” (undressed).

Nod (n.) — sleep. Ex., “I think I’l cop a nod.”

Ofay (n.) — white person.

Off the cob (adj.) — corny, out of date.

Off-time jive (n.) — a sorry excuse, saying the wrong thing.

Orchestration (n.) — an overcoat.

Out of the world (adj.) — perfect rendition. Ex., “That sax chorus was out of the world.”

Ow! — an exclamation with varied meaning. When a beautiful chick passes by, it’s “Ow!”; and when someone pulls an awful pun, it’s also “Ow!”

Pad (n.) — bed.

Pecking (n.) — a dance introduced at the Cotton Club in 1937.

Peola (n.) — a light person, almost white.

Pigeon (n.) — a young girl.

Pops (n.) — salutation for all males (see gate; Jack).

Pounders (n.) — policemen.

Queen (n.) — a beautiful girl.

Rank (v.) — to lower.

Ready (adj.) — 100 per cent in every way. Ex., “That fried chicken was ready.”

Ride (v.) — to swing, to keep perfect tempo in playing or singing.

Riff (n.) — hot lick, musical phrase.

Righteous (adj.) — splendid, okay. Ex., “That was a righteous queen I dug you with last black.”

Rock me (v.) — send me, kill me, move me with rhythym.

Ruff (n.) — quarter, twenty-five cents.

Rug cutter (n.) — a very good dancer, an active jitterbug.

Sad (adj.) — very bad. Ex., “That was the saddest meal I ever collared.”

Sadder than a map (adj.) — terrible. Ex., “That man is sadder than a map.”

Salty (adj.) — angry, ill-tempered.

Sam got you — you’ve been drafted into the army.

Send (v.) — to arouse the emotions. (joyful). Ex., “That sends me!”

Set of seven brights (n.) — one week.

Sharp (adj.) — neat, smart, tricky. Ex., “That hat is sharp as a tack.”

Signify (v.) — to declare yourself, to brag, to boast.

Skins (n.) — drums.

Skin-beater (n.) — drummer (see hide-beater).

Sky piece (n.) — hat.

Slave (v.) — to work, whether arduous labor or not.

Slide your jib (v.) — to talk freely.

Snatcher (n.) — detective.

So help me — it’s the truth, that’s a fact.

Solid (adj.) — great, swell, okay.

Sounded off (v.) — began a program or conversation.

Spoutin’ (v.) — talking too much.

Square (n.) — an unhep person (see icky; Jeff).

Stache (v.) — to file, to hide away, to secrete.

Stand one up (v.) — to play one cheap, to assume one is a cut-rate.

To be stashed (v.) — to stand or remain.

Susie‑Q (n.) — a dance introduced at the Cotton Club in 1936.

Take it slow (v.) — be careful.

Take off (v.) — play a solo.

The man (n.) — the law.

Threads (n.) — suit, dress or costuem (see drape; dry-goods).

Tick (n.) — minute, moment. Ex., “I’ll dig you in a few ticks.” Also, ticks are doubled in accounting time, just as money isdoubled in giving “line.” Ex., “I finaled to the pad this early bright at tick twenty” (I got to bed this morning at ten o’clock).

Timber (n.) — toothipick.

To dribble (v.) — to stutter. Ex., “He talked in dribbles.”

Togged to the bricks — dressed to kill, from head to toe.

Too much (adj.) — term of highest praise. Ex., “You are too much!”

Trickeration (n.) — struttin’ your stuff, muggin’ lightly and politely.

Trilly (v.) — to leave, to depart. Ex., “Well, I guess I’ll trilly.”

Truck (v.) — to go somewhere. Ex., “I think I’ll truck on down to the ginmill (bar).”

Trucking (n.) — a dance introduced at the Cotton Club in 1933.

Twister to the slammer (n.) — the key to the door.

Two cents (n.) — two dollars.

Unhep (adj.) — not wise to the jive, said of an icky, a Jeff, a square.

Vine (n.) — a suit of clothes.

V‑8 (n.) — a chick who spurns company, is independent, is not amenable.

What’s your story? — What do you want? What have you got to say for yourself? How are tricks? What excuse can you offer? Ex., “I don’t know what his story is.”

Whipped up (adj.) — worn out, exhausted, beat for your everything.

Wren (n.) — a chick, a queen.

Wrong riff — the wrong thing said or done. Ex., “You’re coming up on the wrong riff.”

Yarddog (n.) — uncouth, badly attired, unattractive male or female.

Yeah, man — an exclamation of assent.

Zoot (adj.) — exaggerated

Zoot suit (n.) — the ultimate in clothes. The only totally and truly American civilian suit.

BONUS MUSICAL INSTRUMENT SUPPLEMENT

Guitar: Git Box or Belly-Fiddle

Bass: Doghouse

Drums: Suitcase, Hides, or Skins

Piano: Storehouse or Ivories

Saxophone: Plumbing or Reeds

Trombone: Tram or Slush-Pump

Clarinet: Licorice Stick or Gob Stick

Xylophone: Woodpile

Vibraphone: Ironworks

Violin: Squeak-Box

Accordion: Squeeze-Box or Groan-Box

Tuba: Foghorn

Electric Organ: Spark Jiver

Related Content:

A 1932 Illustrated Map of Harlem’s Night Clubs: From the Cotton Club to the Savoy Ballroom

Duke Ellington’s Symphony in Black, Starring a 19-Year-old Billie Holiday

Ayun Halliday is an author, homeschooler, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday

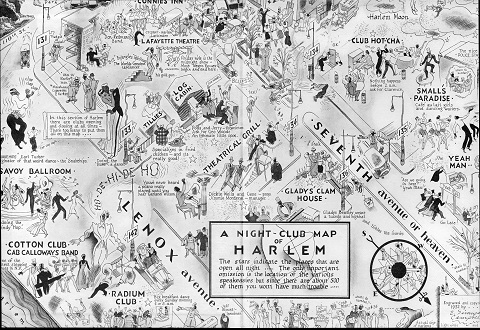

Read More...A 1932 Illustrated Map of Harlem’s Night Clubs: From the Cotton Club to the Savoy Ballroom

Harlem’s undergoing another Renaissance of late. Crime’s down, real estate prices are up, and throngs of pale-faced hipsters are descending to check the area out.

Sure, something’s gained, but something’s lost, too.

For today’s holiday in Harlem, we’re going to climb in the Wayback Machine. Set the dial for 1932. Don’t forget your map. (Click the image above to view a larger version.)

This delirious artifact comes courtesy of Elmer Simms Campbell (1906–1971), an artist whose race proved an impediment to career advancement in his native Midwest. Not long after relocating to New York City, he had the good fortune to be befriended by the great Cab Calloway, star of the Cotton Club. Hi-de-hi-de-hi-de-ho! Check the lower left corner of your map.

You may notice that the compass rose deviates rather drastically from established norms. As you’ve no doubt heard, the Bronx is up, and the Battery’s down, but not in this case. Were you to choose those trees in the upper left corner as your starting point, you’d be at the top of Central Park, basically equidistant from the east and west sides. (Take the 2 or the 3 to 110th St…)

But keep in mind that this map is not drawn to scale. I know it looks like the joints are jumping from the second you step off the curb, but in reality, you’ll need to hoof it 21 blocks from the top of Central Park to 131st street for things to start cookin’. Hopefully, this geographical liberty won’t get you too hot under the collar. And if it does, well, it may be Prohibition, but stress-relieving beverages await you in every location listed, as well as in some 500 speakeasies Campbell allowed to remain on the down low.

If that doesn’t do it for you, there’s a guy selling reefer across the street from Earl “Snakehips” Tucker.

As you stagger back and forth between Seventh Avenue to Lenox (now referred to as Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard and Malcolm X), bear in mind that Campbell was the first African-American cartoonist to be nationally published in the New Yorker, Playboy, and Esquire, whose bug-eyed, now retired mascot, Esky, was a Campbell creation.

In the end, he was an extremely successful illustrator, though few of his creations are reflective of his race.

The map above, which did double duty as endpapers for Calloway’s autobiography, Of Minnie the Moocher and Me, is far closer to home.

Right above, see Cab Calloway perform “Hotcha Razz Ma Tazz” at the famous Cotton Club, in Harlem, 1935.

Related Content:

Watch Langston Hughes Read Poetry from His First Collection, The Weary Blues (1958)

Duke Ellington’s Symphony in Black, Starring a 19-Year-old Billie Holiday

Ayun Halliday is an author, Hoos-Yorker, homeschooler, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday

Read More...