|

Digest of new articles at openculture.com, your source for the best cultural and educational resources on the web ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

|

|

The New York Public Library opened in 1911, an age of magnificence in American city-building. Eighteen years before that, writes architect-historian Witold Rybczynski, “Chicago’s Columbian Exposition provided a real and well-publicized demonstration of how the unruly American downtown could be tamed though a partnership of classical architecture, urban landscaping, and heroic public art.” Modeled after Europe’s urban civilization, the “White City” built on the ground of the Columbian Exposition inspired a generation of American architects and planners including John Nolen, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., and John Carrère, co-designer of the New York Public Library.

Carrère appears in the Architectural Digest tour video of the NYPL building above — or at least his bust does, prominently placed as it is on the landing of one of the grand staircases leading up from the main entrance. The staircases are marble, as is much of else; when the NYPL opened after nine years of construction, so the tour’s narration informs us, it did so as the largest marble-clad structure in the country.

On the soundtrack we have not just one […]

|

|

|

|

|

Despite having been around for well over a century, the Oreo cookie has managed to retain certain mysteries. Why, for example, does it never come apart evenly? Though different Oreo-eaters prefer different methods of Oreo-eating, an especially popular approach to the world’s most popular cookie involves twisting it open before consumption. That action produces two separate chocolate wafers, but as even kindergarteners know from long and frustrating experience, the crème filling sticks only to one side. It seems that no manual technique, no matter how advanced, can split the contents of an Oreo close to evenly, and only recently have a team of researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology sought an explanation.

This endeavor necessitated an investigation of the Oreo’s rheology — the study of the flow of matter, especially liquids but also “soft solids” like crème filling. Like all scientific research, it involved intensive experimentation, and even the invention of a new measurement device: in this case, a simple 3D-printable “Oreometer” (seen in animated action above) that uses pennies and rubber bands.

With it the […]

|

|

|

|

|

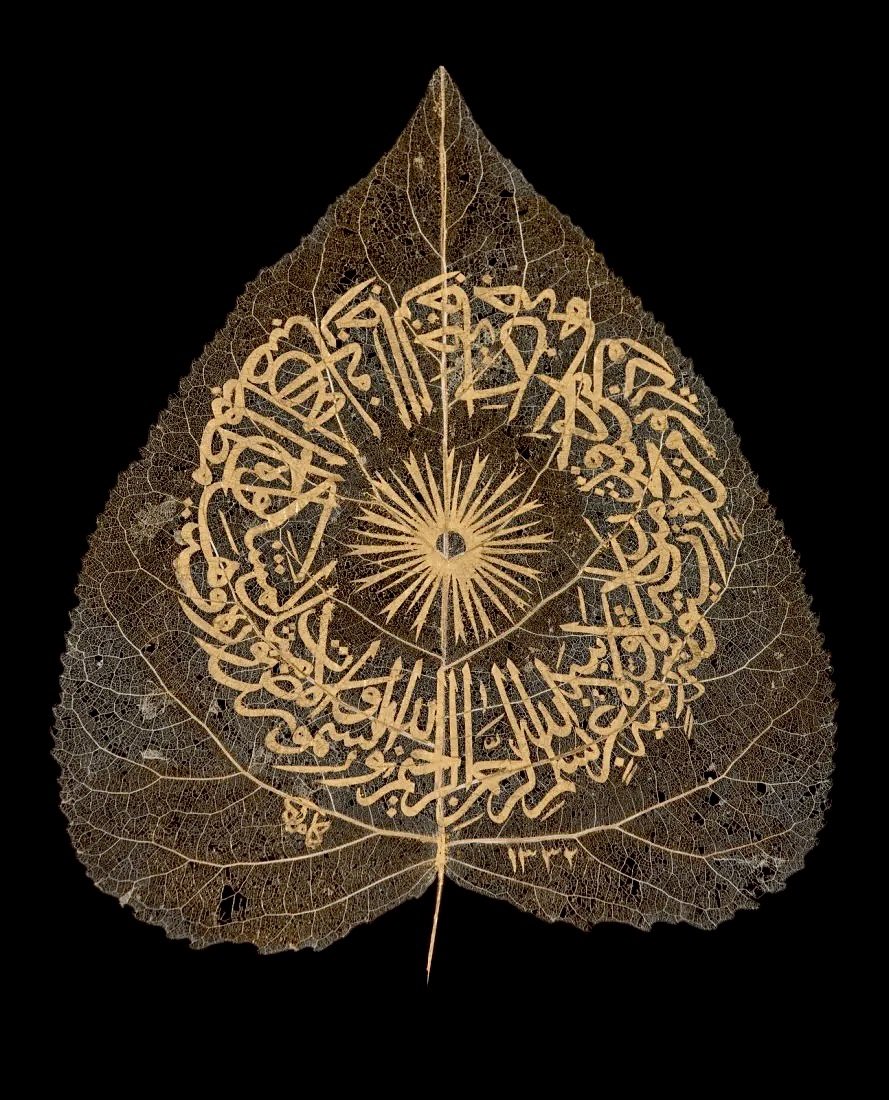

The study of Islamic calligraphy is “almost inexhaustible,” begins German-born Harvard professor Annemarie Schimmel’s Calligraphy and Islamic Culture, “given the various types of Arabic script and the extension of Islamic culture” throughout the Arabian Peninsula, Persia, Africa, and the Ottoman Empire. The first calligraphic script, called Ḥijāzī, allegedly originated in the Hijaz region, birthplace of the Prophet Muhammad himself. Another version called Kūfī, “one of the earliest extant Islamic scripts,” developed and flourished in the “Abbasid Baghdad,” Anchi Hoh writes for the Library of Congress, “a major center of culture and learning during the classical Islamic age.”

Despite the long and venerable history of calligraphy around the Islamic world, there is good reason for the saying that the Qur’an was “revealed in Mecca, recited in Egypt, and written in Istanbul.” The Ottomans refined Arabic calligraphy to its highest degree, bringing the art into a “golden age… unknown since the Abbasid era,” Hoh writes.

“Ottoman calligraphers adopted [master Abbasid calligrapher] Ibn Muqlah’s six styles and elevated them to new […]

|

|

|

|

|

In the National Gallery there hangs a portrait of an unknown woman, painted by an unknown artist around 1470 somewhere in southwestern Germany. This may sound like an artwork of little note, but it does boast one highly conspicuous mark of distinction: a housefly. It’s not that the portraitist was in such thrall to realism that he included an insect that happened to drop into the sitting; at first glance, the fly looks as if it belongs to our reality, and has alighted on the canvas itself. Why would a painter, presumably commissioned at the considerable expense of the sitter’s family, include such a seemingly bizarre detail? National Gallery curator Francesca Whitlum-Cooper offers answers in the video below.

“It’s a joke,” says Whitlum-Cooper. “And it’s a joke that works on different levels, because on the one hand, the fly has been tricked into thinking this is a real headdress,” fooled by the painter’s mastery of that most difficult color for light and shadow, white.

“But obviously there’s a double joke, because we, looking […]

|

|

|

|