|

Digest of new articles at openculture.com, your source for the best cultural and educational resources on the web ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

|

|

Among the ranks of Open Culture readers, there are no doubt more than a few art-history majors. Perhaps you’ve studied the subject yourself, at one time or another — and perhaps you find that by now, you remember only certain scattered artists, works, and movements. What you need is a grand narrative, a broad story of art itself, and that’s just what you’ll find in the video above from Youtube channel Behind the Masterpiece. True to its title, “A Brief History of Art Movements” briefly describes, and provides a host of visual examples to illustrate, 22 phases in the development of art in just 23 minutes.

The journey begins in prehistory, with cave paintings from 40,000 years ago apparently created “as a way to share information.” Then comes the art of antiquity, when increasingly literate societies “started creating the earliest naturalistic images of human beings,” not least to enforce “religious and political ideologies.” The religiosity intensified in the Middle Ages, when artists “depicted clear, iconic images of religious figures” — as well as their oddly […]

|

|

|

|

|

Back in 1993, the Beat writer William S. Burroughs wrote and narrated a 21 minute claymation Christmas film. And, as you can well imagine, it’s not your normal happy Christmas flick. Nope, this film – The Junky’s Christmas – is all about Danny the Carwiper, a junkie, who spends Christmas Day trying to score a fix. Eventually he finds the Christmas spirit when he shares some morphine with a young man suffering from kidney stones, giving him the “immaculate fix.” There you have it. And, oh, did we mention that the film was produced by Francis Ford Coppola?

Related Content:

William S. Burroughs’ Scathing “Thanksgiving Prayer,” Shot by Gus Van Sant

Andy Warhol’s Christmas Art

Dementia 13: The Film That Took Francis Ford Coppola From Schlockster to Auteur

|

|

|

|

|

Attention young artists: don’t let your day job kill your dream.

In the mid-70s, David Godlis kept body and soul together by working as an assistant in a photography studio, but his ambition was to join the ranks of his street photographer idols – Robert Frank, Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand, and Lee Friedlander, to name a few.

As Godlis told Sergio Burns of Street Photography, “the 60’s and 70’s were great for photographers:”

The 35mm camera was kind of like the new affordable technology of the day. Like having an iPhone you couldn’t talk on. Cool to look at, fun to use. Photography was only just beginning to be considered an art form. Which left plenty of room for inventing yourself. The movie Blow-Up showed off the kind of cool lifestyle that could be had. Photography seemed both adventurous and artistic. There were obviously a million career paths for photographers back then. From the sublime to the ridiculous. But plenty of opportunities to experiment and find your own way.

Still, it’s a tough proposition, […]

|

|

|

|

|

Though regarded by many as near-impossibly difficult to judge, avant-garde art can be put to its own test of time: does it still feel new ten, twenty, fifty, a hundred years later? Now that most of Walter Ruttmann’s short animated films have passed the century mark, we can with some confidence say they pass that test. A few years ago, we featured here on Open Culture his Lichtspiel Opus 1, the first avant-garde animation ever made. Now, with this playlist, you can watch it and several of its successors, which together date from the years 1921 through 1925.

“A trained architect and painter,” writes Cartoon Brew’s Amid Amidi, Ruttmann “worked as a graphic designer prior to becoming involved with film. He fought in WWI, suffered a nervous breakdown and spent time recovering in a sanatorium.”

It was after that harrowing experience that he plunged into the still-new medium of animation, and he evidently brought the combined aesthetic refinement of architecture, painting, and graphic design with him. His four-part Opus series (top) shows us “how […]

|

|

|

|

|

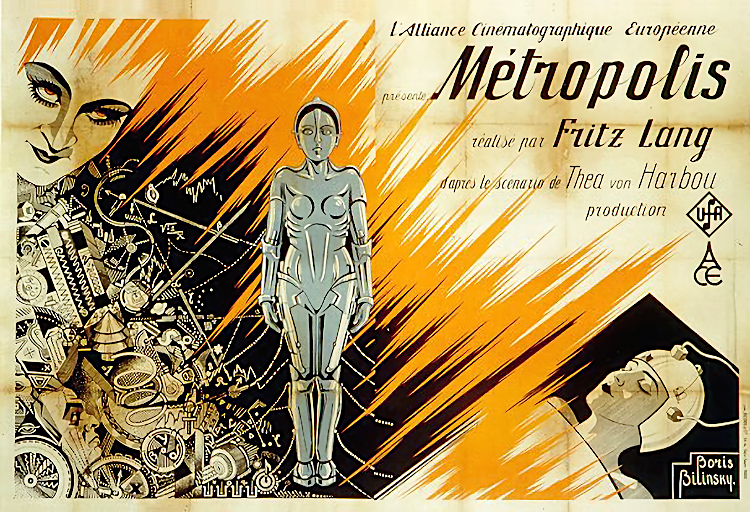

Of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, the critic Siegfried Kracauer wrote that “the Americans relished its technical excellence; the English remained aloof; the French were stirred by a film which seemed to them a blend of Wagner and Krupp, and on the whole an alarming sign of Germany’s vitality.” By Wagner, Kracauer of course meant the composer; Krupp referred to the arms manufacturer Friedrich Krupp AG. We must remember that Metropolis first came out in the Germany of 1927, and thus into a sociopolitical context growing more volatile by the moment.

But the film also came out in the golden age of silent cinema, and every serious moviegoer in the world must have been enormously eager for a glimpse of the spectacle of the elaborate dystopian future Lang and his collaborators had put onscreen.

And screen around the world that spectacle did, albeit in a version censored and otherwise cut in a variety of ways that Lang found terribly displeasing. However bowdlerized the Metropolis seen by so many back then, it proved […]

|

|

|

|