|

Digest of new articles at openculture.com, your source for the best cultural and educational resources on the web ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

|

|

Attention young artists: don’t let your day job kill your dream.

In the mid-70s, David Godlis kept body and soul together by working as an assistant in a photography studio, but his ambition was to join the ranks of his street photographer idols – Robert Frank, Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand, and Lee Friedlander, to name a few.

As Godlis told Sergio Burns of Street Photography, “the 60’s and 70’s were great for photographers:”

The 35mm camera was kind of like the new affordable technology of the day. Like having an iPhone you couldn’t talk on. Cool to look at, fun to use. Photography was only just beginning to be considered an art form. Which left plenty of room for inventing yourself. The movie Blow-Up showed off the kind of cool lifestyle that could be had. Photography seemed both adventurous and artistic. There were obviously a million career paths for photographers back then. From the sublime to the ridiculous. But plenty of opportunities to experiment and find your own way.

Still, it’s a tough proposition, […]

|

|

|

|

|

Though regarded by many as near-impossibly difficult to judge, avant-garde art can be put to its own test of time: does it still feel new ten, twenty, fifty, a hundred years later? Now that most of Walter Ruttmann’s short animated films have passed the century mark, we can with some confidence say they pass that test. A few years ago, we featured here on Open Culture his Lichtspiel Opus 1, the first avant-garde animation ever made. Now, with this playlist, you can watch it and several of its successors, which together date from the years 1921 through 1925.

“A trained architect and painter,” writes Cartoon Brew’s Amid Amidi, Ruttmann “worked as a graphic designer prior to becoming involved with film. He fought in WWI, suffered a nervous breakdown and spent time recovering in a sanatorium.”

It was after that harrowing experience that he plunged into the still-new medium of animation, and he evidently brought the combined aesthetic refinement of architecture, painting, and graphic design with him. His four-part Opus series (top) shows us “how […]

|

|

|

|

|

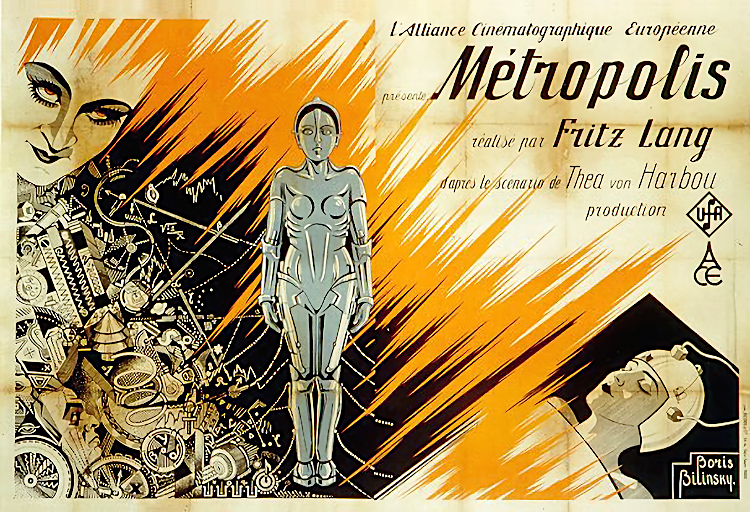

Of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, the critic Siegfried Kracauer wrote that “the Americans relished its technical excellence; the English remained aloof; the French were stirred by a film which seemed to them a blend of Wagner and Krupp, and on the whole an alarming sign of Germany’s vitality.” By Wagner, Kracauer of course meant the composer; Krupp referred to the arms manufacturer Friedrich Krupp AG. We must remember that Metropolis first came out in the Germany of 1927, and thus into a sociopolitical context growing more volatile by the moment.

But the film also came out in the golden age of silent cinema, and every serious moviegoer in the world must have been enormously eager for a glimpse of the spectacle of the elaborate dystopian future Lang and his collaborators had put onscreen.

And screen around the world that spectacle did, albeit in a version censored and otherwise cut in a variety of ways that Lang found terribly displeasing. However bowdlerized the Metropolis seen by so many back then, it proved […]

|

|

|

|

|

M. C. Escher, Hannah Arendt, Hieronymus Bosch, Hilma af Kint, Stanley Kubrick: if you’re a regular reader of Open Culture, you’re no doubt fascinated some or all of these figures. Now, thanks to film distributor Kino Lorber, you can watch entire films about them on Youtube. Having evidently put a good deal of energy toward expanding their Youtube channel in recent months, Kino Lorber has uploaded such documentaries as M. C. Escher: Journey to Infinity, Vita Activa: The Spirit of Hannah Arendt, Hieronymous Bosch: Touched by the Devil, Beyond the Visible: Hilma af Kint, and Filmworker (about Kubrick’s right-hand man, the late Leon Vitali) — all of them free to watch.

So far, Kino Lorber’s playlist of free documentaries contains 80 films, a number that may vary depending on your location. Some popular selections focus on music: that of Elvis Presley, that of Levon Helm and The Band, that of Greenwich Village in the nineteen-sixties and seventies.

But the documentary is […]

|

|

|

|

|

The late Angelo Badalamenti composed music for singers like Marianne Faithfull and Nina Simone, for movies like The City of Lost Children and National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation, and even for the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona. But of all his musical work, no piece is more likely to begin playing in our minds at the mention of his name than the theme from Twin Peaks, the ABC series that both mystified and enraptured audiences in the early nineteen-nineties. Looking back, one would expect anything less from a prime-time show co-created by David Lynch. And though Twin Peaks‘ initial run would come to only three seasons, Lynch and Badalamenti’s collaboration would continue for decades thereafter.

It was with his work for Lynch, in fact, that Badalamenti first broke through as a film composer: 1986’s Blue Velvet may have established Lynch as America’s foremost popular “art house” auteur, but it also introduced its viewers the world over to the seductive and unsettling beauty of Badalamenti’s music.

That film’s song “Mysteries of Love” (with its Lynch-penned lyrics sung […]

|

|

|

|