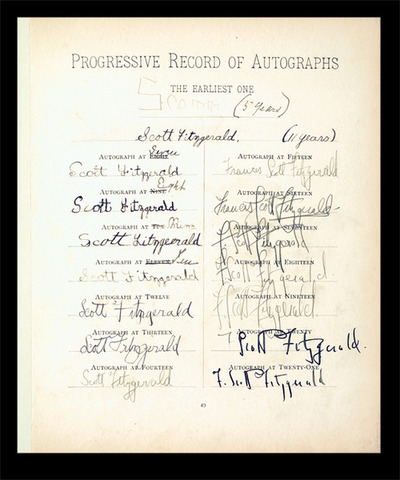

Take, for example, the evolution of Fitzgerald’s signature (above). From the labored scrawls of a five year-old, to the practiced script of an eleven-year-old schoolboy, to the experimental teenaged poses, we see the lettering get looser, more stylized, then tighten up again as it assumes its own mature identity in the confidently elegant near-calligraphy of the 21-year-old Fitzgerald–an evolution that traces the writer’s creative growth from uncertain but passionate youth to disciplined artist. Alright, maybe that’s all nonsense. I’m no expert. The practice of handwriting analysis, or graphology, is generally a forensic tool used to identify the marks of criminal suspects and detect forgeries, not a mindreading technique, although it does get used that way. One site, for example, provides an analysis of one of Fitzgerald’s 1924 letters to Carl Van Vechten. From the minute characteristics of the Gatsby novelist’s script, the analyst divines that he is “creative,” “artistic,” and appreciates the finer things in life. Color me a little skeptical.

But maybe there is something to my theory of Fitzgerald’s growing maturity and self-conscious certainty as evidenced by his signatures. He published This Side of Paradise to great acclaim three years after the final signature above. In the prior signatures, we see him struggling for control as he wrote and revised an earlier unpublished novel called The Romantic Egotist, which Fitzgerald himself told editor Perkins was “a tedious, disconnected casserole.” The outsized, extravagant lettering of the artist in his late teens is nothing if not “romantic.” But Fitzgerald achieved just enough control in his short life to write a veritable treasure chest of stories (many brilliant and some just plain silly) and a handful of novels, including, of course, the one for which he’s best known. Most of the rest of the time, as most everyone knows, he was kind of a mess.

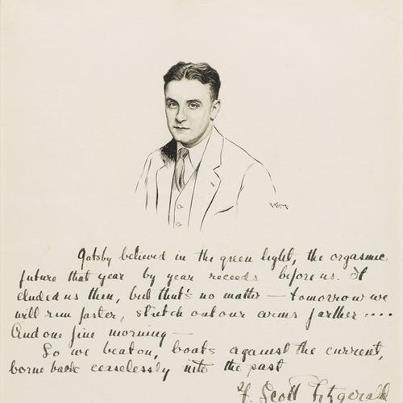

Try a little amateur handwriting analysis of your own on the last sentence of The Great Gatsby, written in Fitzgerald’s own hand below a portrait of the writer by artist Robert Kastor.

via I always wanted to be a Tenenbaum

Josh Jones is a doctoral candidate in English at Fordham University and a co-founder and former managing editor of Guernica / A Magazine of Arts and Politics.

Leave a Reply