Who doesn’t treasure a handmade present?

As the years go by, we may begin to offload the ill-fitting sweaters, the never lit sand cast candles, and the Styrofoam ball snowmen. But a present made of words takes up very little space, and it has the Ghost of Christmas Past’s power to instantly evoke the sender as they once were.

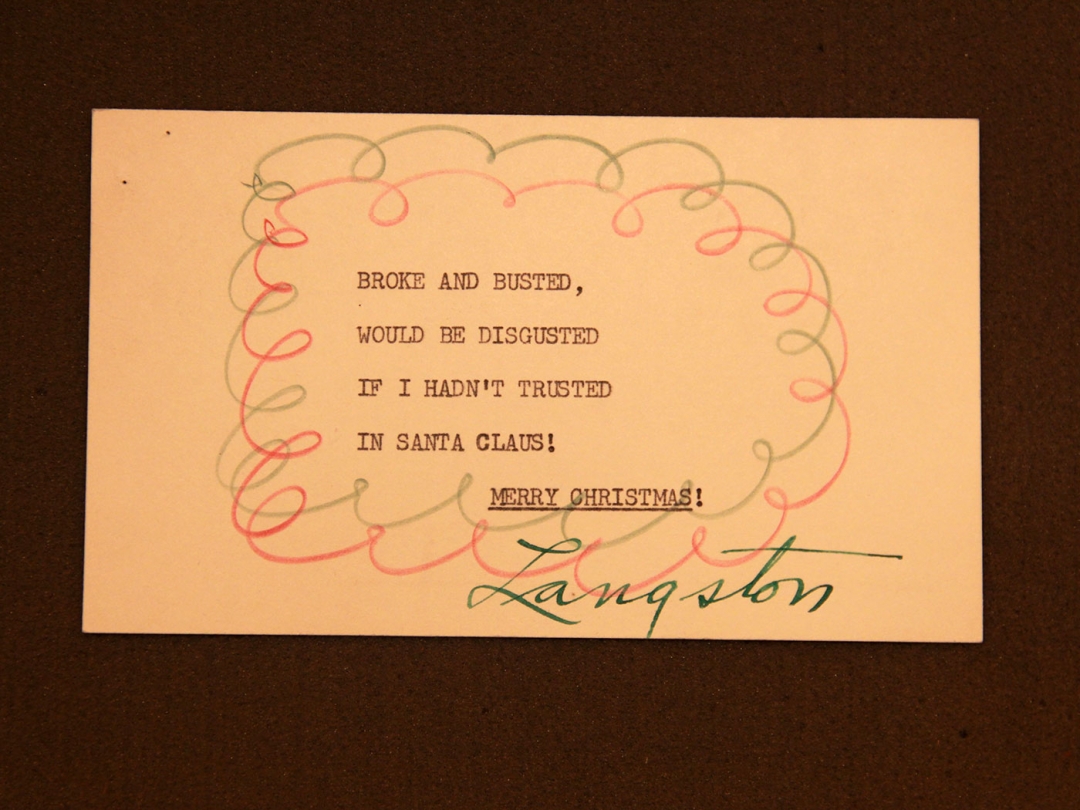

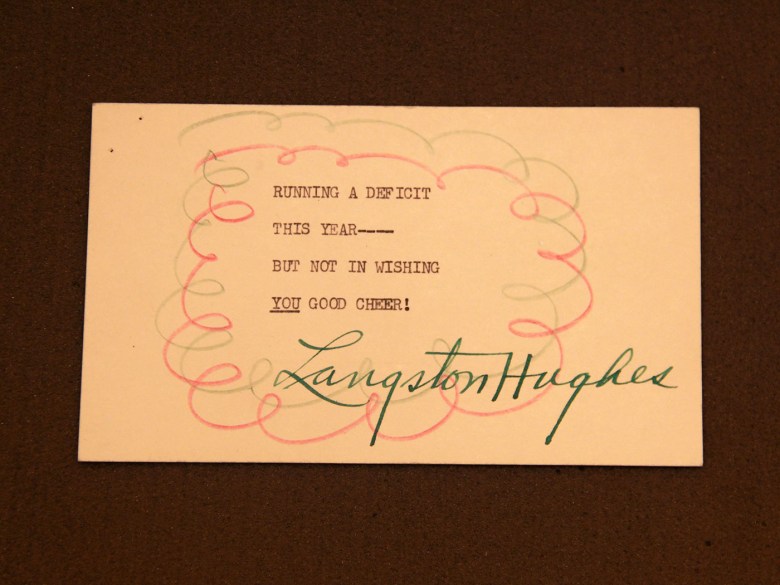

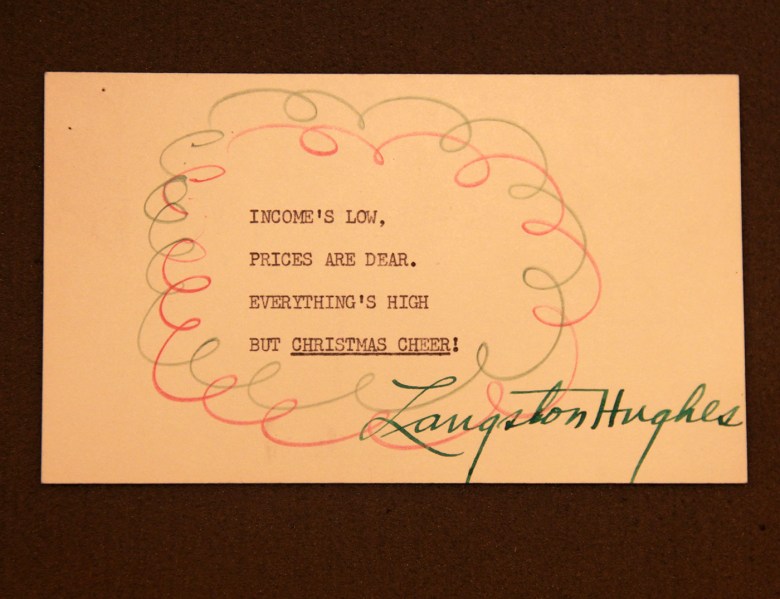

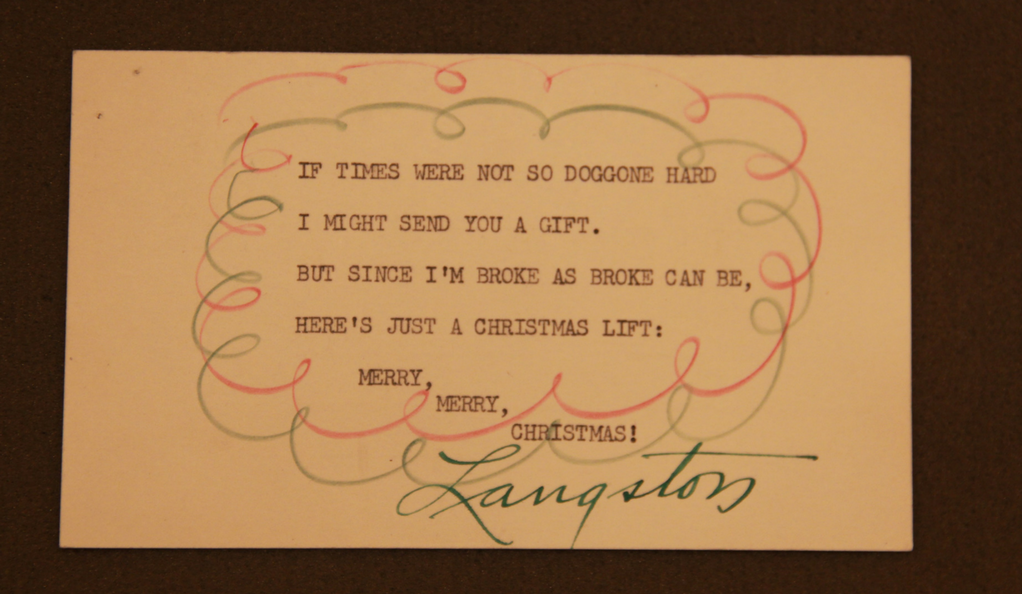

Seventy years ago, poet Langston Hughes, too skint to go Christmas shopping, sent everyone on his gift list simple, homemade holiday postcards. Typed on white cardstock, each signed card was embellished with red and green pencils and mailed for the price of a 3¢ stamp.

As biographer Arnold Rampersad notes:

The last weeks of 1950 found him nevertheless in a melancholy mood, his spirits sinking lower again as he again became a target of red-baiting.

The year started auspiciously with The New York Times praising his libretto for The Barrier, an opera based on his play, Mulatto: A Tragedy of the Deep South. But the opera was a commercial flop, and positive reviews for his book Simple Speaks His Mind failed to translate into the hoped-for sales.

Although he had recently purchased an East Harlem brownstone with an older couple who doted on him as they would a son, providing him with a sunny, top floor workspace, 1950 was far from his favorite year.

His typewritten holiday couplets took things out on a jaunty note, while paying light lip service to his plight.

Maybe we can aspire to the same…

Hughes’ handmade holiday cards reside in the Langston Hughes Papers in Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, along with holiday cards specific to the African-American experience received from friends and associates.

via the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University

Related Content:

Langston Hughes Reads Langston Hughes

A Simple, Down-to-Earth Christmas Card from the Great Depression (1933)

Hear Neil Gaiman Read A Christmas Carol Just as Dickens Read It

How Joni Mitchell’s Song of Heartbreak, “River,” Became a Christmas Classic

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and theater maker in NYC.