As we’ve noted before, the English coffeehouse has served as a staging ground for radical, sometimes revolutionary social change. Certainly this was the case during the Enlightenment, as it was with the salons in France. And yet, by the early 20th century it seems, coffee shops in London had grown scarcer and more humdrum. That is until 1953 when the Moka Bar, the UK’s first Italian espresso bar, opened in Soho. On his blog The Great Wen, Peter Watts describes its arrival as “a momentous event”:

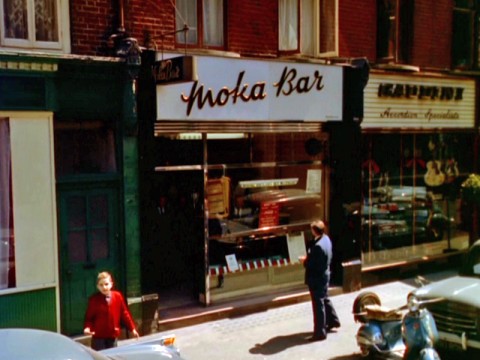

London’s first proper coffee shop—one equipped with a Gaggia coffee machine—opened at 29 Frith Street. This was a place where teenagers too young for pubs could come and gather, and it is said by some that the introduction of this coffee bar prompted the youth culture explosion that soon changed social life in Britain forever.

“By 1972,” Watts writes, “coffee bars were everywhere and the teenage revolution was firmly established.” Places like the Moka Bar might seem like the ideal place for countercultural maven William S. Burroughs—a London resident from the late sixties to early seventies—to hobnob with young dissidents and outsiders. Burroughs, who so approvingly refers the possibly apocryphal anarchist pirate colony of Libertatia in his Cities of the Red Night, would, one might think, appreciate the budding anarchism of British youth culture, which would flower into punk soon enough.

But rather than joining the coffee bar scene, the cantankerous Burroughs had taken to frequenting “plush gentlemen’s shops of the area, not to mention the ‘Dilly Boys,’ young male prostitutes who hustled for clients outside the Regent Palace Hotel.”

And he had grown increasingly disillusioned with London, fuming, writes Ted Morgan in Burroughs biography Literary Outlaw, “at what he was paying for his hole-in-the-wall apartment with a closet for a kitchen” and at the rising price of utilities. “Burroughs,” Morgan tells us, “began to feel that he was in enemy territory.” And he thought the Moka coffee bar should pay the price for his indignities.

There, “on several occasions a snarling counterman had treated him with outrageous and unprovoked discourtesy, and served him poisonous cheesecake that made him sick.” Burroughs “decided to retaliate by putting a curse on the place.” He chose a means of attack that he’d earlier employed against the Church of Scientology, “turning up… every day,” writes Watts, “taking photographs and making sound recordings.” Then he would play them back a day or so later on the street outside the Moka. “The idea,” writes Morgan, “was to place the Moka Bar out of time. You played back a tape that had taken place two days ago and you superimposed it on what was happening now, which pulled them out of their time position.”

Burroughs also connected the method to the Watergate recordings, the Garden of Eden, and the theories of Alfred Korzybski. The trigger for the magical operation was, in his words, “playback.” In a very strange essay called “Feedback from Watergate to the Garden of Eden,” from his collection Electronic Revolution, Burroughs described his operation in detail, a disruption, he wrote, of a “control system.”

Now to apply the 3 tape recorder analogy to this simple operation. Tape recorder 1 is the Moka Bar itself it is pristine condition. Tape recorder 2 is my recordings of the Moka Bar vicinity. These recordings are access. Tape recorder 2 in the Garden of Eden was Eve made from Adam. So a recording made from the Moka Bar is a piece of the Moka Bar. The recording once made, this piece becomes autonomous and out of their control. Tape recorder 3 is playback. Adam experiences shame when his discraceful behavior is played back to him by tape recorder 3 which is God. By playing back my recordings to the Moka Bar when I want and with any changes I wish to make in the recordings, I become God for this local. I effect them. They cannot effect me.

The theory made perfect sense to Burroughs, who believed in a Magical Universe ruled by occult forces and who experimented heavily with Scientology, Crowley-an Magick, and the orgone energy of Wilhelm Reich. The attack on the Moka worked, or at least Burroughs believed it did. “They are seething in there,” he wrote, “I have them and they know it.” On October 30th, 1972 the establishment closed its doors—perhaps a consequence of those rising rents that so irked the Beat writer—and the location became the Queens Snack Bar.

The audio-visual cut-up technique Burroughs used in his attack against the Moka Bar was a method derived by Burroughs and Brion Gysin from their experiments with written “cut-ups,” and Burroughs applied it to film as well. At the top of the post, see an interpretive “meditation” based on Burroughs’ use of audio/visual “magical weapons” and incorporating his recordings. On YouTube, you can watch “The Cut Ups,” a short film Burroughs himself made in 1966 with cinematographer Antony Balch, a disorienting illustration of the cut up technique.

Not limited to attacking annoying London coffeehouse owners, Burroughs’ supposedly magical interventions in reality were in fact the fullest expression of his creativity. As Ted Morgan writes, “the single most important thing about Burroughs was his belief in the magical universe. The same impulse that lead him to put out curses was, as he saw it, the source of his writing.” Read much more about Burroughs’ theory and practice in Matthew Levi Stevens’ essay “The Magical Universe of William S. Burroughs,” and hear the author himself discourse on the paranormal, tape cut-ups, and much more in the lecture below from a writing class he gave in June, 1986.

via The Great Wen

Related Content:

When William S. Burroughs Joined Scientology (and His 1971 Book Denouncing It)

William S. Burroughs on the Art of Cut-up Writing

William S. Burroughs’ Short Class on Creative Reading

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply