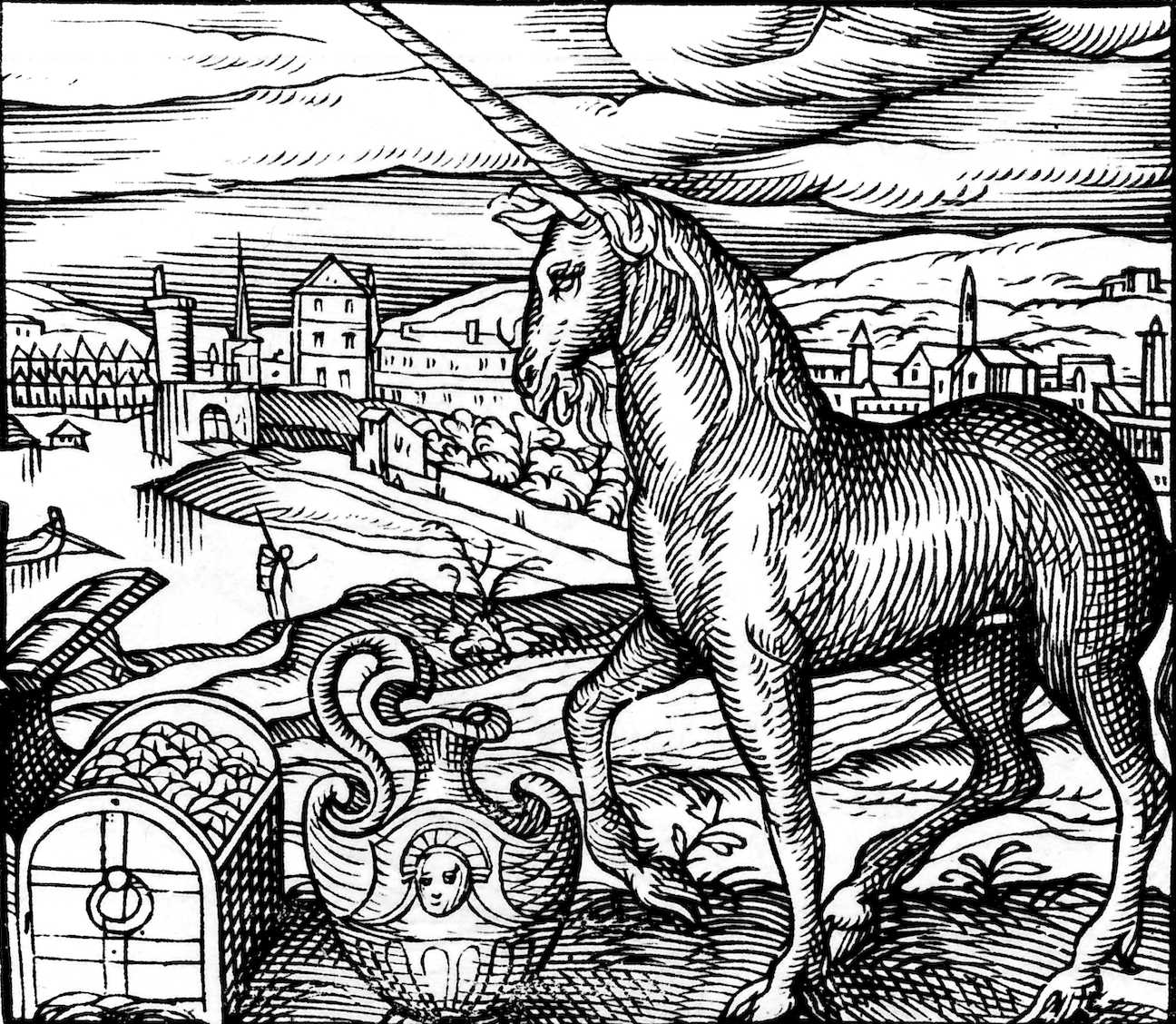

Whether or not we believe that the cards of the tarot have supernatural powers, we all think of them primarily as tools for divination. It might seem as if they’ve played that cultural role since time immemorial, but in fact, that particular use only goes back to the eighteenth century. They were, at first, playing cards, used for a game known as tarocchi in Renaissance Italy. That was the original purpose of the oldest tarot cards in possession of the Victoria and Albert Museum, which you can see unboxed by curator Ruth Hibbard in the video above. Throughout its fifteen minutes, Hibbard and two colleagues also “unbox” five other decks produced across the half-millennium of tarot history.

These include the early eighteenth-century Minchiate Deck, whose name refers to a slightly more complex Florentine card game that evolved alongside tarot. The word itself possibly originates from the term sminchiare, “to play your highest card” (though in Sicilian dialect today, it has a rather different meaning).

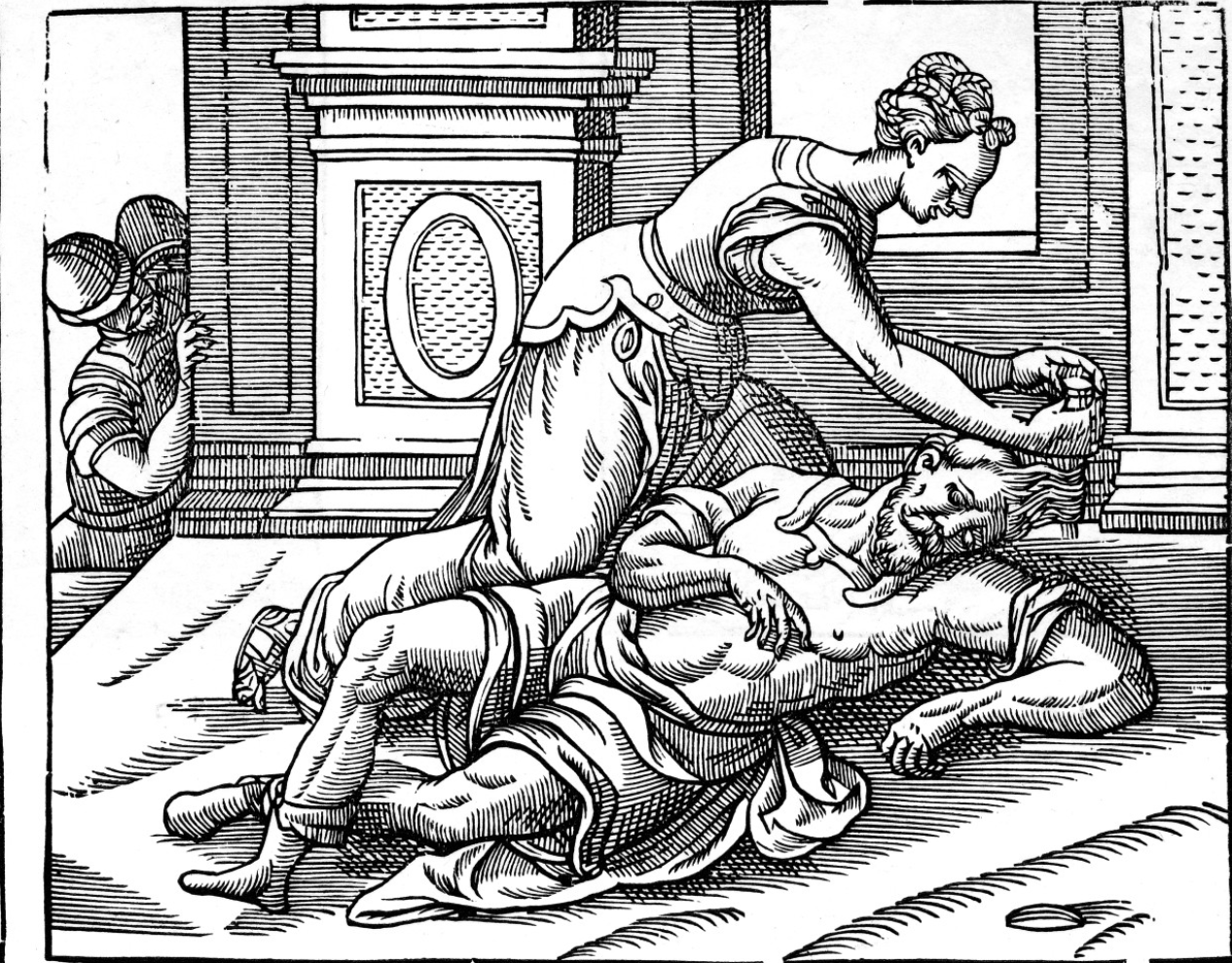

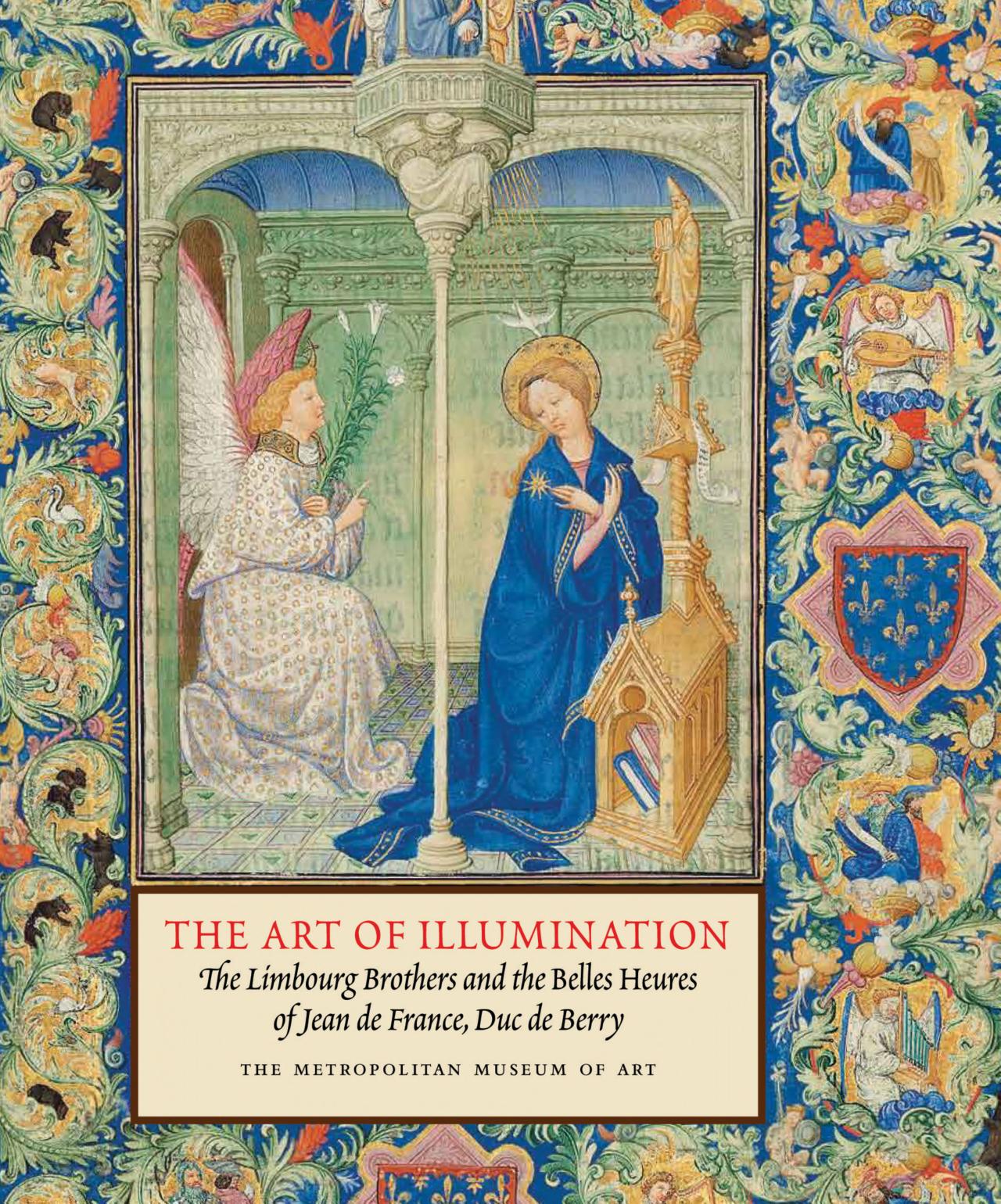

Later, circa 1807, comes Le Petit Oracle des Dames, “the petite oracle of women,” the earliest deck in the video expressly produced for cartomancy, or prediction of the future through cards — albeit only as a form of light entertainment for gatherings of ladies. A decade or two later, out came the luxurious Tarocco Soprafino, which bears lavish illustrations made with copper-plate engraving and colored stenciling.

The V&A also has an early twentieth-century tarot deck with rich, lively art created by the occultist Pamela Colman-Smith, whose work has previously been featured here on Open Culture. “What makes these cards so great is that they’re just so rich with mythology and symbology and multilayered meaning,” says curator Beckie Billingham, “allowing you to read the cards in many different ways.” That’s even true of the much more thematically deliberate deck that follows, an example from the early two-thousands that brings into our digital century the mission of tarot art to “reveal clandestine knowledge and the hidden powers at work in the world.” Computers, drones, Aldous Huxley, world wars, the World Wide Web: perhaps these cards let us see our future, but they certainly give us a clear view on our present.

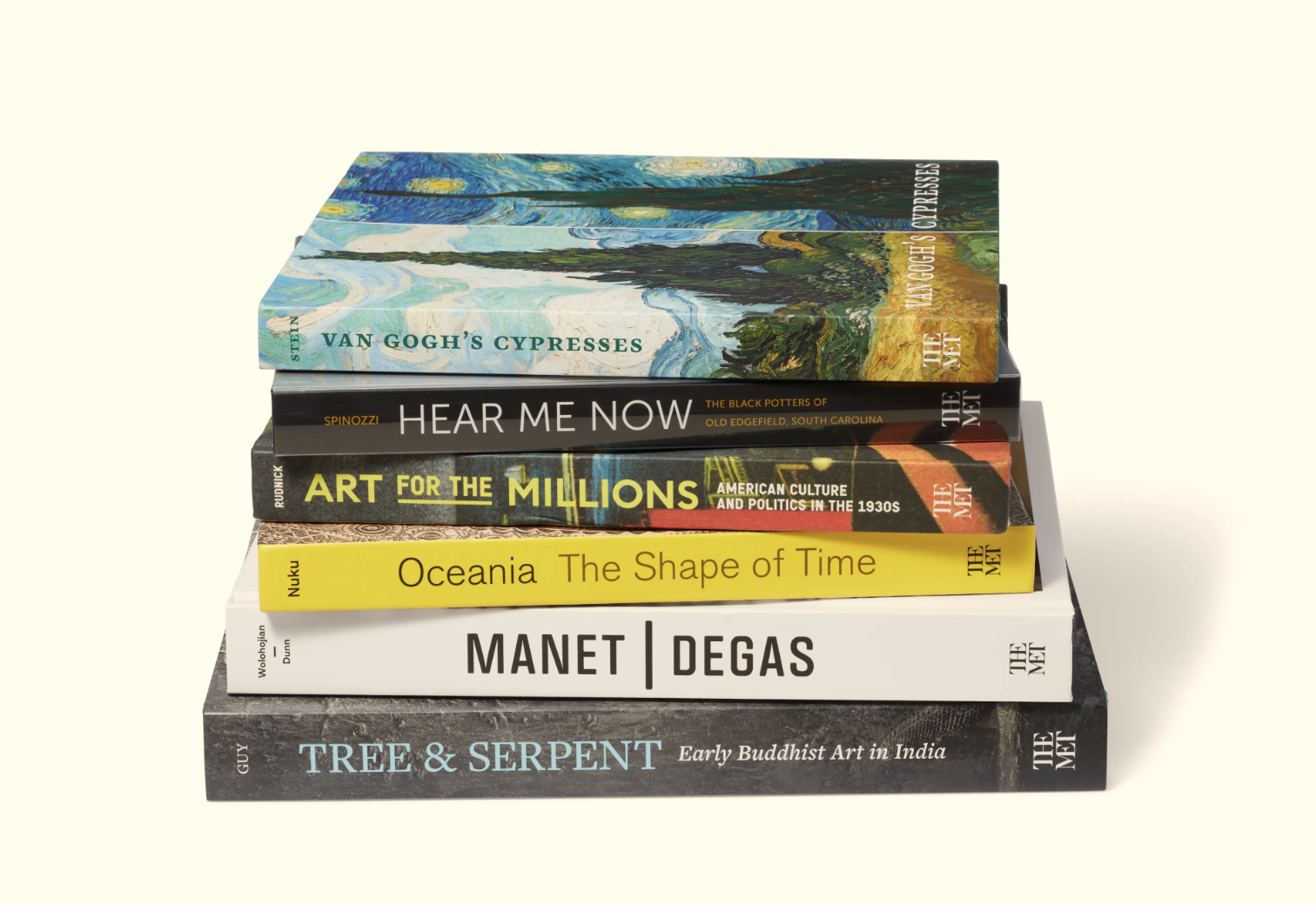

Related content:

Meet the Forgotten Female Artist Behind the World’s Most Popular Tarot Deck (1909)

Behold the Sola-Busca Tarot Deck, the Earliest Complete Set of Tarot Cards (1490)

Alejandro Jodorowsky Explains How Tarot Cards Can Give You Creative Inspiration

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.