These days, we hear much said on social media — surely too much — in favor of the “hustle culture” and the “grind mindset” (or, abbreviated for maximum efficiency, the “grindset”). Dedication to your work is to be admired, provided that the work itself is of value, but the more of a day’s hours you devote to it, the likelier returns are to diminish. Oliver Burkeman, a popular writer on productivity and time management, has made this point in a variety of ways, usually returning to the same finding: look at the work habits of a range of luminaries including Charles Darwin, Henri Poincaré, Thomas Jefferson, Charles Dickens, Virginia Woolf, J.G. Ballard, Ingmar Bergman, Alice Munro, John le Carré, and Adam Smith, and you’ll find that they all put in about three or four hours of concentrated effort per day.

“You almost certainly can’t consistently do the kind of work that demands serious mental focus for more than about three or four hours a day,” Burkeman writes on his site. If you do work of that kind, it would behoove you to “just focus on protecting four hours — and don’t worry if the rest of the day is characterized by the usual scattered chaos.”

Doing so entails making an “internal psychological move: to give up demanding more of yourself than three or four hours of daily high-quality mental work.” You’ll also finally have to “abandon the delusion that if you just managed to squeeze in a bit more work, you’d finally reach the commanding status of feeling ‘in control’ and ‘on top of everything’ at last.”

The “the truly valuable skill here,” Burkeman continues, “isn’t the capacity to push yourself harder, but to stop and recuperate despite the discomfort of knowing that work remains unfinished, emails unanswered, other people’s demands unfulfilled.” This is easier said than done, of course, but any attempt to implement what Burkeman calls the “three-to-four-hour rule” must begin with a bit of trial and error: about when best in the day to schedule those hours, but also about how best to eliminate distractions during those hours. Underneath all this lies the need to accept life’s finitude, as Burkeman explains in the interview at the top of the post, with its implication that we can only get so much done in what he often describes as our allotted 4,000 weeks — minus however many thousand we’ve already lived so far.

To think more about managing your time effectively, see Burkerman’s books: Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals and also Meditations for Mortals: Four Weeks to Embrace Your Limitations and Make Time for What Counts.

Related Content:

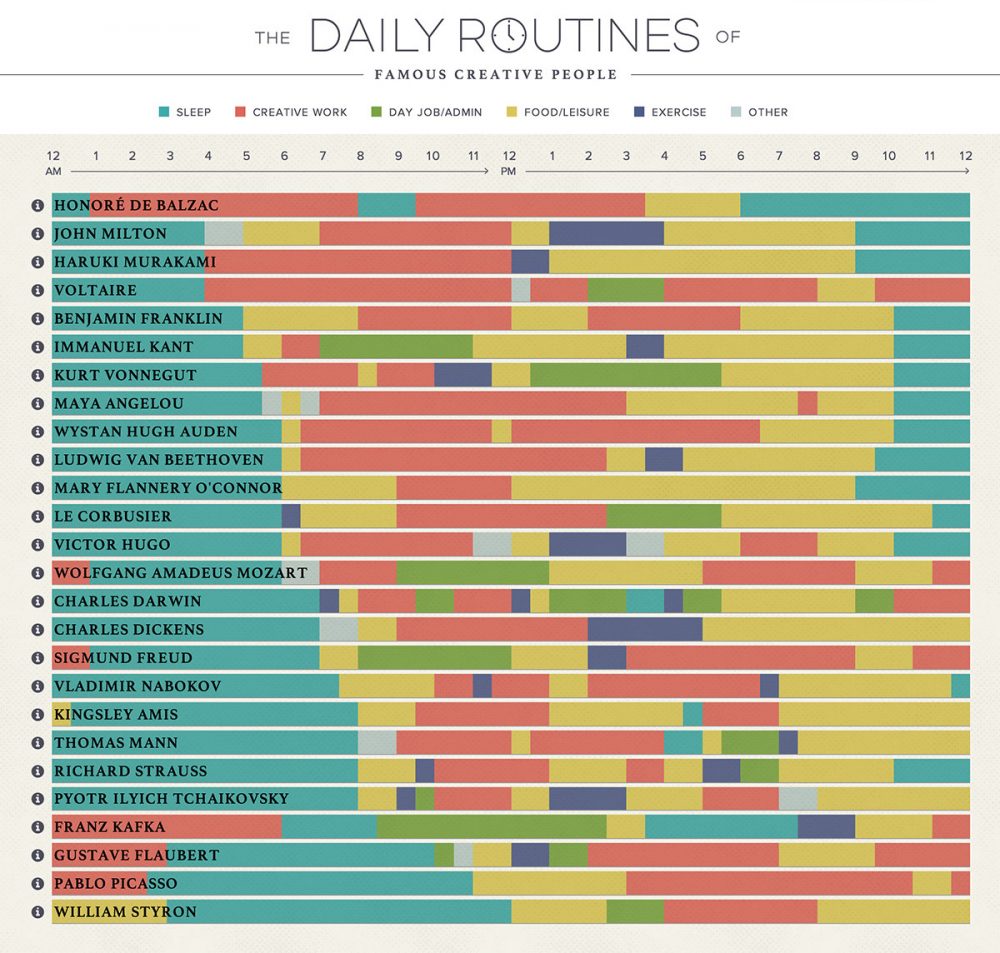

The Daily Routines of Famous Creative People, Presented in an Interactive Infographic

Write Only 500 Words Per Day and Publish 50+ Books: Graham Greene’s Writing Method

David Lynch Explains How Simple Daily Habits Enhance His Creativity

Haruki Murakami’s Daily Routine: Up at 4:00 a.m., 5–6 Hours of Writing, Then a 10K Run

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.