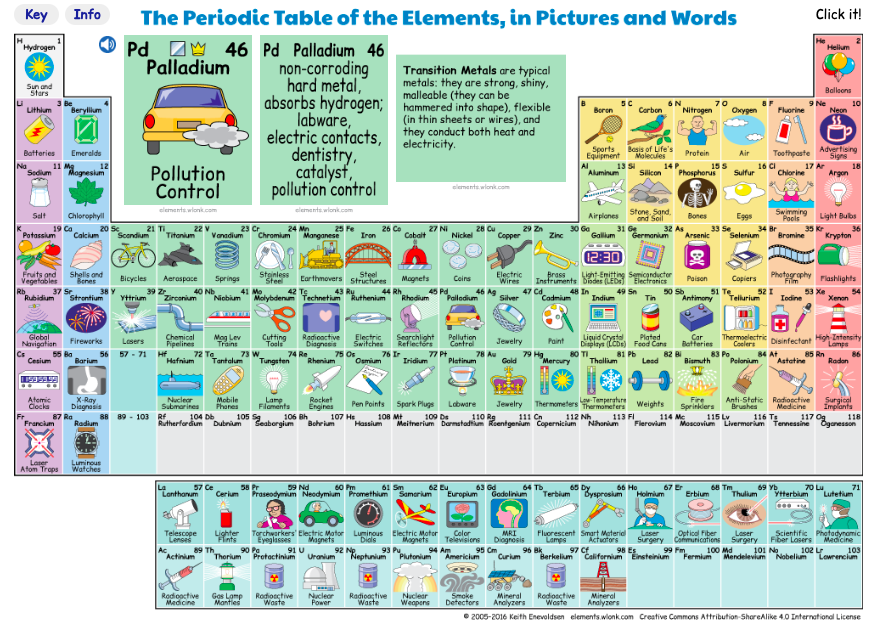

Marie Curie’s 1911 Nobel Prize win, her second, for the discovery of radium and polonium, would have been cause for public celebration in her adopted France, but for the nearly simultaneous revelation of her affair with fellow physicist Paul Langevin, the fellow standing to the right of a 32-year-old Albert Einstein in the above group photo from the 1911 Solvay Conference in Physics.

Both stories broke while Curie—unsurprisingly, the sole woman in the photo—was attending the conference in Brussels.

Equally unsurprisingly, the press preferred le scandale to la réalisation scientifique. Sex sells, then and now.

The fires of radium which beam so mysteriously…have just lit a fire in the heart of one of the scientists who studies their action so devotedly; and the wife and the children of this scientist are in tears.…

—Le Journal, November 4, 1911

There’s no denying that the affair was painful for Langevin’s family, particularly his wife, Jeanne, who supplied the media with incriminating letters from Curie to her husband. She must have been aware that Curie would be the one to bear the brunt of the public’s disapproval. Double standards with regard to gender are nothing new.

A furious throng gathered outside of Curie’s house and anti-Semitic papers, dissatisfied with labeling the pioneering scientist a mere home wrecker, declared—erroneously—that she was Jewish. The timeline was tweaked to suggest that Curie had taken up with Langevin prior to her husband’s death. Fellow radiochemist Bertram Boltwood seized the opportunity to declare that “she is exactly what I always thought she was, a detestable idiot.”

In the midst of this, Einstein, who had made Curie’s acquaintance at the conference, proved himself a true friend with a “don’t let the bastards get you down” letter, written on November 23. Other than a delicate allusion to Langevin as a person with whom he felt privileged to be in contact, he refrained from mentioning the cause of her misfortune.

A friendly word can go a long way in times of disgrace, and Einstein supplied his new friend with some stoutly unequivocal ones, denouncing the scandalmongers as “reptiles” feasting on sensationalistic “hogwash”:

Highly esteemed Mrs. Curie,

Do not laugh at me for writing you without having anything sensible to say. But I am so enraged by the base manner in which the public is presently daring to concern itself with you that I absolutely must give vent to this feeling. However, I am convinced that you consistently despise this rabble, whether it obsequiously lavishes respect on you or whether it attempts to satiate its lust for sensationalism! I am impelled to tell you how much I have come to admire your intellect, your drive, and your honesty, and that I consider myself lucky to have made your personal acquaintance in Brussels. Anyone who does not number among these reptiles is certainly happy, now as before, that we have such personages among us as you, and Langevin too, real people with whom one feels privileged to be in contact. If the rabble continues to occupy itself with you, then simply don’t read that hogwash, but rather leave it to the reptile for whom it has been fabricated.

With most amicable regards to you, Langevin, and Perrin, yours very truly,

A. Einstein

PS I have determined the statistical law of motion of the diatomic molecule in Planck’s radiation field by means of a comical witticism, naturally under the constraint that the structure’s motion follows the laws of standard mechanics. My hope that this law is valid in reality is very small, though.

That deliberately geeky postscript amounts to another sweet show of support. Perhaps it fortified Curie when a week later, she received a letter from Nobel Committee member Svante Arrhenius, urging her to skip the Prize ceremony in Stockholm. Curie rejected Arrhenius’ suggestion thusly:

The prize has been awarded for the discovery of radium and polonium. I believe that there is no connection between my scientific work and the facts of private life. I cannot accept … that the appreciation of the value of scientific work should be influenced by libel and slander concerning private life.

For a more in-depth look at Marie Curie’s nightmarish November, refer to “Honor and Dishonor” the sixteenth chapter in Barbara Goldsmith’s Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2018.

Related Content:

Marie Curie’s Research Papers Are Still Radioactive a Century Later

Marie Curie Invented Mobile X‑Ray Units to Help Save Wounded Soldiers in World War I

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator and theater maker in NYC.