I have taken more out of alcohol than alcohol has taken out of me. — Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill had a reputation as a brilliant statesman and a prodigious drinker.

The former prime minister imbibed throughout the day, every day. He also burned through 10 daily cigars, and lived to the ripe old age of 90.

His comeback to Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery’s boast that he neither smoked nor drank, and was 100 percent fit was “I drink and smoke, and I am 200 percent fit.”

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt marveled “that anyone could smoke so much and drink so much and keep perfectly well.”

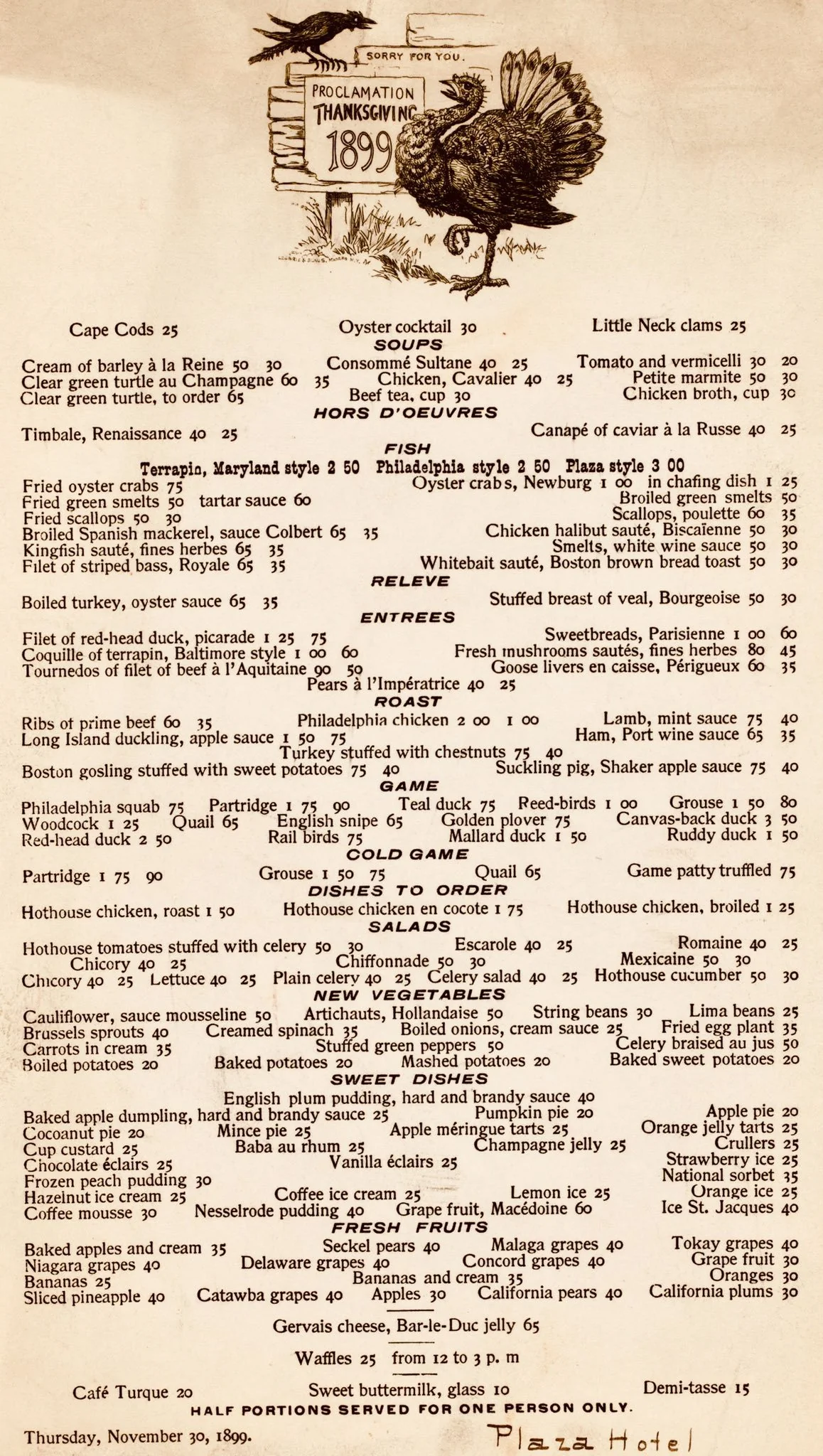

In No More Champagne: Churchill and His Money, author David Lough documents Churchill’s disastrous alcohol expenses, as well as the bottle count at Chartwell, his Kentish residence. Here’s the tally for March 24,1937:

180 bottles and 30 half bottles of Pol Roger champagne

20 bottles and 9 half bottles of other champagne

100+ bottles of claret

117 bottles and 389 half bottles of Barsac

13 bottles of brandy

5 bottles of champagne brandy

7 bottles of liqueur whisky

All that liquor was not going to drink itself.

Did Churchill have a hollow leg? An extraordinarily high tolerance? An uncanny ability to mask his intoxication?

Whiskey sommelier Rex Williams, a founder of the Whiskey Tribe YouTube channel, and podcast host Andrew Heaton endeavor to find out, above, by dedicating a day to the British Bulldog’s drinking regimen.

They’re not the first to undertake such a folly.

The Daily Telegraph’s Harry Wallop documented a similar adventure in 2015, winding up queasy, and to judge by his 200 spelling mistakes, cognitively impaired.

Williams and Heaton’s on-camera experiment achieves a Drunk History vibe and telltale flushed cheeks.

Here’s the drill, not that we advise trying it at home:

BREAKFAST

An eye opener of Johnnie Walker Red — just a splash — mixed with soda water to the rim.

Follow with more of the same throughout the morning.

This is how Churchill, who often conducted his morning business abed in a dressing gown, managed to average between 1 — 3 ounces of alcohol before lunch.

Apparently he developed a taste for it as a young soldier posted in what is now Pakistan, when Scotch not only improved the flavor of plain water, ‘once one got the knack of it, the very repulsion from the flavor developed an attraction of its own.”

After a morning spent sipping the stuff, Heaton reports feeling “playful and jokey, but not yet violent.”

LUNCH

Time for “an ambitious quota of champagne!”

Churchill’s preferred brand was Pol Roger, though he wasn’t averse to Giesler, Moet et Chandon, or Pommery, purchased from the upscale wine and spirits merchant Randolph Payne & Sons, whose letterhead identified them as suppliers to “Her Majesty The Late Queen Victoria and to The Late King William The Fourth.”

Churchill enjoyed his imperial pint of champagne from a silver tankard, like a “proper Edwardian gent” according to his lifelong friend, Odette Pol-Roger.

Williams and Heaton take theirs in flutes accompanied by fish sticks from the freezer case. This is the point beyond which a hangover is all but assured.

Lunch concludes with a post-prandial cognac, to settle the stomach and begin the digestion process.

Churchill, who declared himself a man of simple tastes — I am easily satisfied with the best — would have insisted on something from the house of Hine.

RESTORATIVE AFTERNOON NAP

This seems to be a critical element of Churchill’s alcohol management success. He frequently allowed himself as much as 90 minutes to clear the cobwebs.

A nap definitely pulls our re-enactors out of their tail spins. Heaton emerges ready to “bluff (his) way through a meeting.”

TEATIME

I guess we can call it that, given the timing.

No tea though.

Just a steady stream of extremely weak scotch and sodas to take the edge off of administrative tasks.

DINNER

More champagne!!! More cognac!!!

“This should be the apex of our wit,” a bleary Heaton tells his belching companion, who fesses up to vomiting upon waking the next day.

Their conclusion? Churchill’s regimen is unmanageable…at least for them.

And possibly also for Churchill.

As fellow Scotch enthusiast Christopher Hitchens revealed in a 2002 article in The Atlantic, some of Churchill’s most famous radio broadcasts, including his famous pledge to “fight on the beaches” after the Miracle of Dunkirk, were voiced by a pinch hitter:

Norman Shelley, who played Winnie-the-Pooh for the BBC’s Children’s Hour, ventriloquized Churchill for history and fooled millions of listeners. Perhaps Churchill was too much incapacitated by drink to deliver the speeches himself.

Or perhaps the great man merely felt he’d earned the right to unwind with a glass of Graham’s Vintage Character Port, a Fine Old Amontillado Sherry or a Fine Old Liquor brandy, as was his wont.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2022.

Related Content

Winston Churchill Gets a Doctor’s Note to Drink Unlimited Alcohol While Visiting the U.S. During Prohibition (1932)

Winston Churchill’s Paintings: Great Statesman, Surprisingly Good Artist

Oh My God! Winston Churchill Received the First Ever Letter Containing “O.M.G.” (1917)

Winston Churchill Goes Backward Down a Water Slide & Loses His Trunks (1934)

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist in NYC.