Western scholarship has had “a bias against studying sensual experience,” writes Reina Gattuso at Atlas Obscura, “the relic of an Enlightenment-era hierarchy that considered taste, touch, and flavor taboo topics for sober academic inquiry.” This does not mean, however, that cooking has been ignored by historians. Many a scholar has taken European cooking seriously, before recent food scholarship expanded the canon. For example, in a 1926 English translation of an ancient Roman cookbook, Joseph Dommers Vehling makes a strong case for the centrality of food scholarship.

“Anyone who would know something worthwhile about the private and public lives of the ancients,” writes Vehling, “should be well acquainted with their table.” Published as Cookery and Dining in Imperial Rome (and available here at Project Gutenberg and at the Internet Archive), it is, he says, the oldest known cookbook in existence.

The book, originally titled De Re Coquinaria, is attributed to Apicius and may date to the 1st century A.C.E., though the oldest surviving copy comes from the end of the Empire, sometime in the 5th century. As with most ancient texts, copied over centuries, redacted, amended, and edited, the original cookbook is shrouded in mystery.

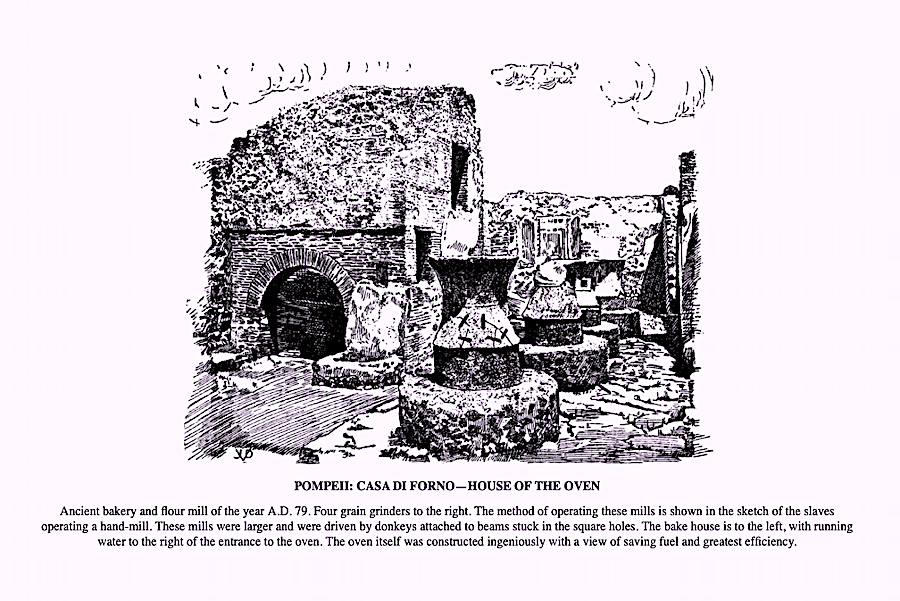

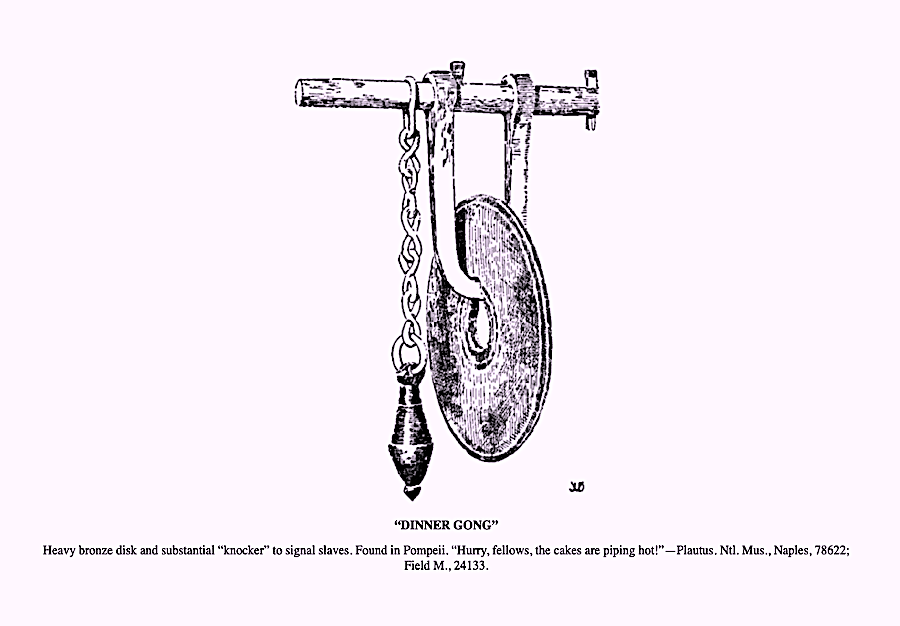

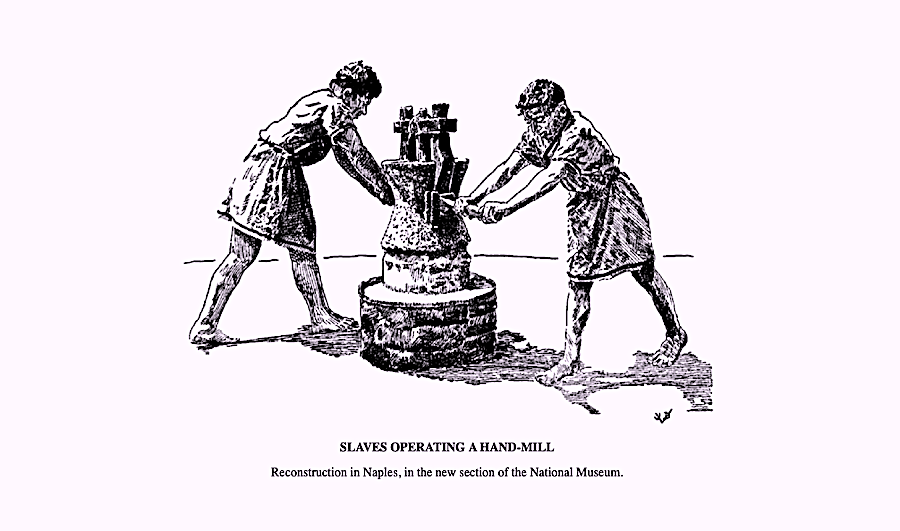

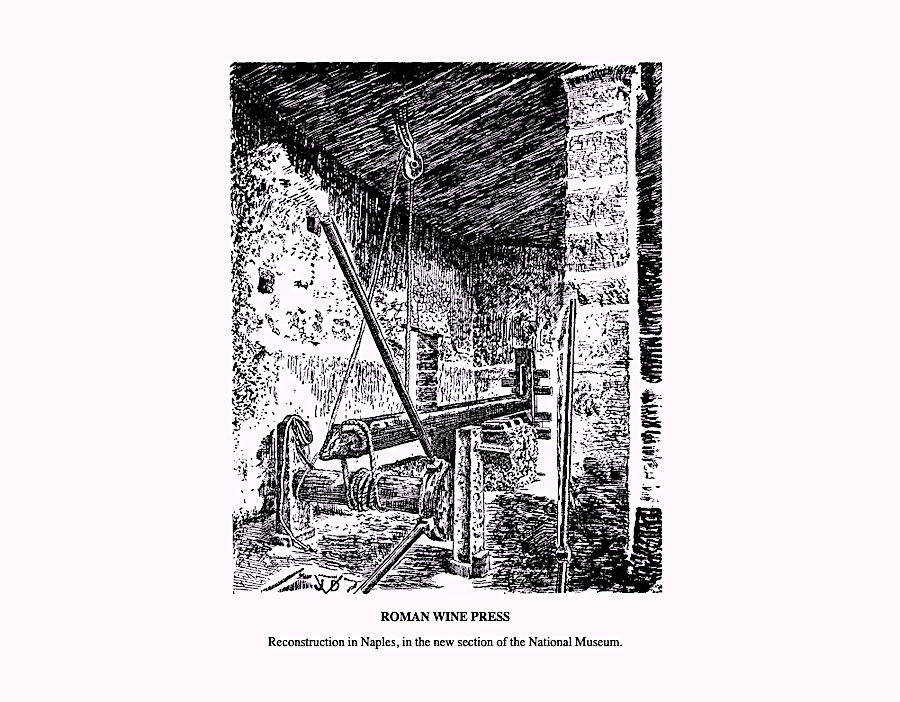

The cookbook’s author, Apicius, could have been one of several “renowned gastronomers of old Rome” who bore the surname. But whichever “famous eater” was responsible, over 2000 years later the book has quite a lot to tell us about the Roman diet. (All of the illustrations here are by Vehling, who includes over two dozen examples of ancient practices and artifacts.)

Meat played an important role, and “cruel methods of slaughter were common.” But the kind of meat available seems to have changed during Apicius’s time:

With the increasing shortage of beef, with the increasing facilities for raising chicken and pork, a reversion to Apician methods of cookery and diet is not only probably but actually seems inevitable. The ancient bill of fare and the ancient methods of cookery were entirely guided by the supply of raw materials—precisely like ours. They had no great food stores nor very efficient marketing and transportation systems, food cold storage. They knew, however, to take care of what there was. They were good managers.

But vegetarians were also well-served. “Apicius certainly excels in the preparation of vegetable dishes (cf. his cabbage and asparagus) and in the utilization of parts of food materials that are today considered inferior.” This apparent need to use everything, and to sometimes heavily spice food to cover spoilage, may have led to an unusual Roman custom. As How Stuff Works puts it, “cooks then were revered if they could disguise a common food item so that diners had no idea what they were eating.”

As for the recipes themselves, well, any attempt to duplicate them will be at best a broad interpretation—a translation from ancient methods of cooking by smell, feel, and custom to the modern way of weights and measures. Consider the following recipe:

WINE SAUCE FOR TRUFFLES

PEPPER, LOVAGE, CORIANDER, RUE, BROTH, HONEY AND A LITTLE OIL.

ANOTHER WAY: THYME, SATURY, PEPPER, LOVAGE, HONEY, BROTH AND OIL.

I foresee much frustrating trial and error (and many hopeful substitutions for things like lovage or rue or “satury”) for the cook who attempts this. Some foods that were plentifully available could cost hundreds now to prepare for a dinner party.

SEAFOOD MINCES ARE MADE OF SEA-ONION, OR SEA CRAB, FISH, LOBSTER, CUTTLE-FISH, INK FISH, SPINY LOBSTER, SCALLOPS AND OYSTERS. THE FORCEMEAT IS SEASONED WITH LOVAGE, PEPPER, CUMIN AND LASER ROOT.

Vehling’s footnotes mostly deal with etymology and define unfamiliar terms (“laser root” is wild fennel), but they provide little practical insight for the cook. “Most of the Apician directions are vague, hastily jotted down, carelessly edited,” much of the terminology is obscure: “with the advent of the dark ages, it ceased to be a practical cookery book.” We learn, instead, about Roman ingredients and home economic practices, inseparable from Roman economics more generally, according to Vehling.

He makes a judgment of his own time even more relevant to ours: “Such atrocities as the willful destruction of huge quantities of food of every description on the one side and the starving multitudes on the other as seen today never occurred in antiquity.” Perhaps more current historians of antiquity would beg to differ, I wouldn’t know.

But if you’re just looking for a Roman recipe that you can make at home, might I suggest the Rose Wine?

ROSE WINE

MAKE ROSE WINE IN THIS MANNER: ROSE PETALS, THE LOWER WHITE PART REMOVED, SEWED INTO A LINEN BAG AND IMMERSED IN WINE FOR SEVEN DAYS. THEREUPON ADD A SACK OF NEW PETALS WHICH ALLOW TO DRAW FOR ANOTHER SEVEN DAYS. AGAIN REMOVE THE OLD PETALS AND REPLACE THEM BY FRESH ONES FOR ANOTHER WEEK; THEN STRAIN THE WINE THROUGH THE COLANDER. BEFORE SERVING, ADD HONEY SWEETENING TO TASTE. TAKE CARE THAT ONLY THE BEST PETALS FREE FROM DEW BE USED FOR SOAKING.

You could probably go with red or white, though I’d hazard Apicius went with a fine vinum rubrum. This concoction, Vehling tells us in a helpful footnote, doubles as a laxative. Clever, those Romans. Read the full English translation of the ancient Roman cookbook here.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 202o.

Related Content:

How to Make the Oldest Recipe in the World: A Recipe for Nettle Pudding Dating Back 6,000 BC

The Oldest Unopened Bottle of Wine in the World (Circa 350 AD)

Cook Real Recipes from Ancient Rome: Ostrich Ragoût, Roast Wild Boar, Nut Tarts & More

How to Bake Ancient Roman Bread Dating Back to 79 AD: A Video Primer

The World’s Oldest Cookbook: Discover 4,000-Year-Old Recipes from Ancient Babylon

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC.

Leave a Reply