“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” So holds the third and most famous of the “three laws” originally articulated by science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke. Even when it was first published in the late nineteen-sixties, Clarke’s third law would have felt true to any resident of the developed world, surrounded by and wholly dependent on advanced technologies whose workings they could scarcely hope to explain. Naturally, it feels even truer now, a quarter of the way into our digital twenty-first century. Indeed, for all we know about how they really work, our credit cards, our smartphones, our computers, and indeed the internet itself might as well be magic.

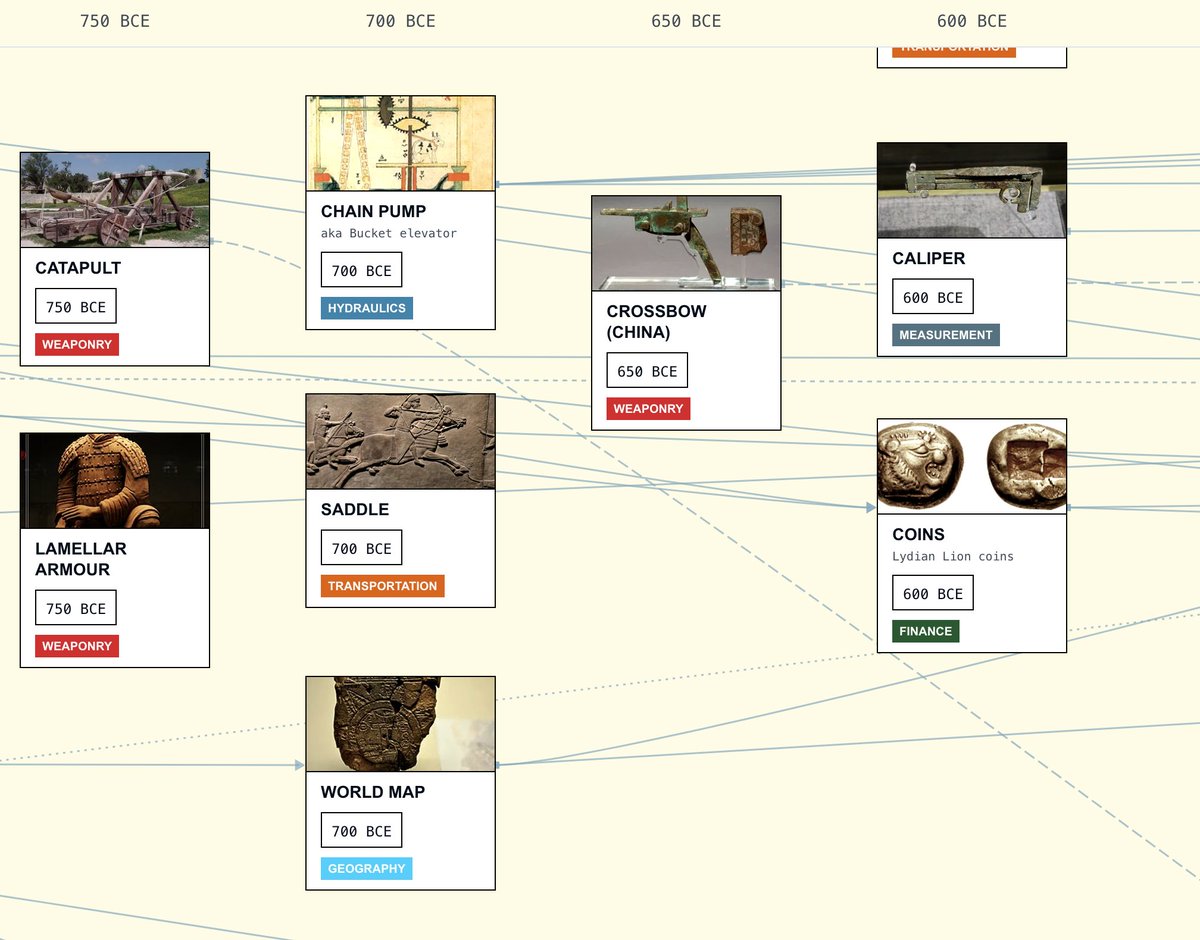

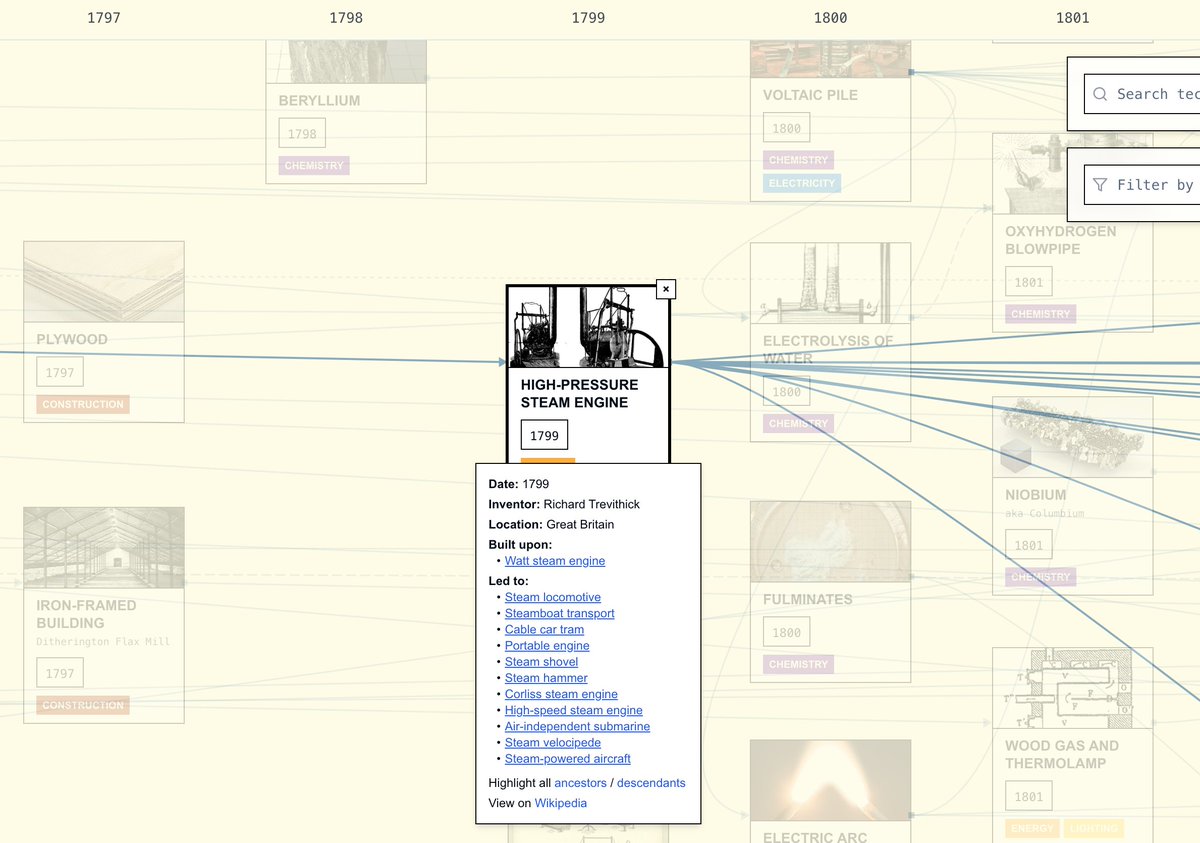

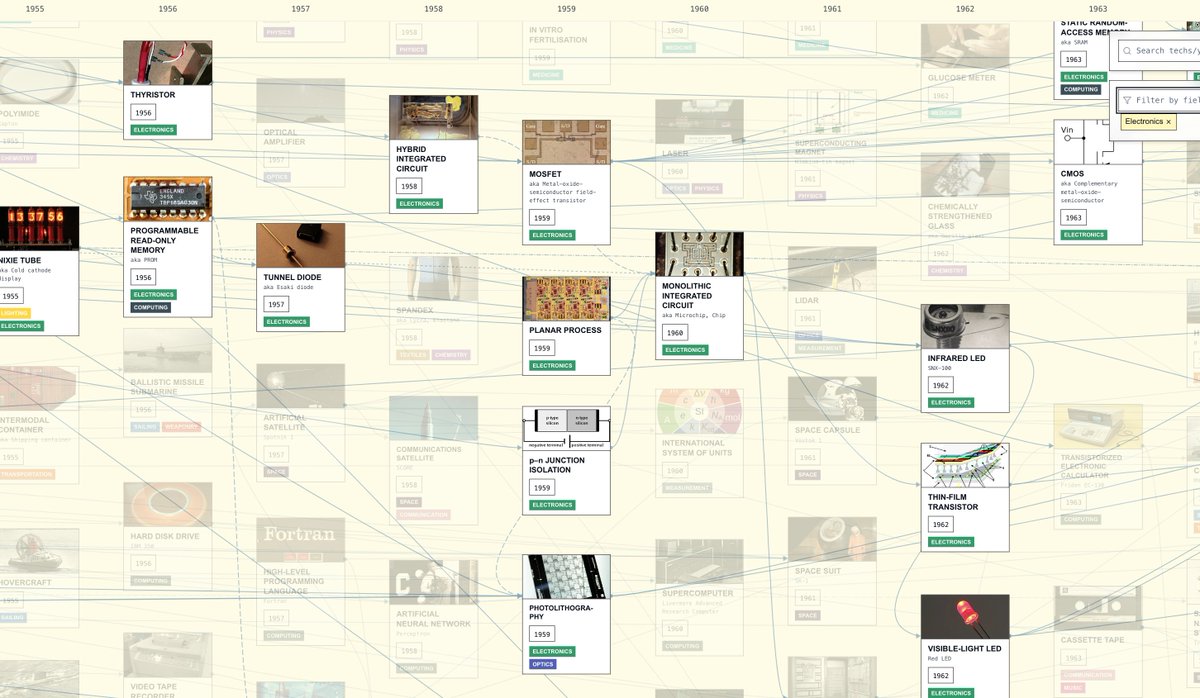

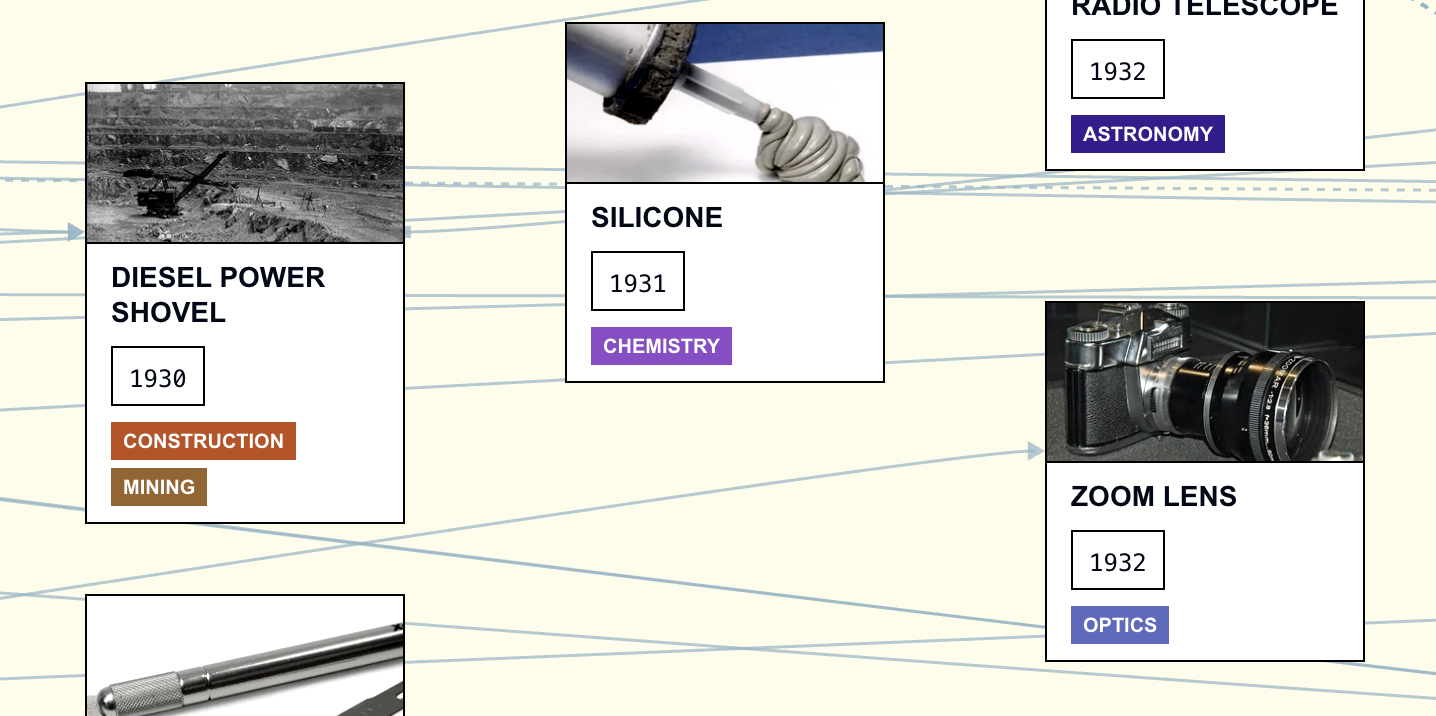

To best understand the technology that increasingly makes up our world, we should attempt to understand the evolution of that technology. Those smartphones, for example, couldn’t have been invented in the form we know them without the previous developments of chemically strengthened glass, the multi-touch screen interface, and the camera phone. Each of those individual technologies also has its predecessors: follow the chain back far enough, and eventually you get to the likes of the mobile radio telephone, invented in 1946; the phased array antenna, invented in 1905; and glass, invented around 1500 BC. These and countless other paths can be traced at the Historical Tech Tree, an ambitious project of writer and programmer Étienne Fortier-Dubois.

Fortier-Dubois credits among his inspirations Sid Meier’s Civilization games, with their all-important “tech trees,” and James Burke’s television series Connections, which highlighted the unpredictable processes by which one innovation could lead to others across the centuries or millennia. Even in the seventies, Fortier-Dubois writes, “Burke was already concerned that our lives depend on technological systems that very few people deeply understand. It is, of course, possible to live without comprehending how computers, money, or airplanes work. But when everything around us feels vaguely magical, reliant on experts whose actions we have no way of verifying, it’s easy to lose trust in technological solutions to our current problems.” He offers the Historical Tech Tree as a potential corrective to that loss of understanding and the enervating attitudes it produces.

Fortier-Dubois himself admits that the project “made me realize how little I knew about the objects around me. I didn’t really know that ‘electronics’ meant controlling the flow of electrons with vacuum tubes or semiconductors, or that refining petroleum into kerosene uses fractional distillation, or that WiFi and bluetooth are just the use of certain radio frequencies that can be detected by a specific kind of chip.” Anyone who explores even this early version of the Historical Tech Tree (which, as of this writing, contains 1886 technologies and 2180 connections between them) will find it an educational experience in the same way, providing as it does not just knowledge about technology but a sense of how much of that knowledge we lack. Our civilization has made its way from stone tools to robotaxis, mRNA vaccines, and LLM chatbots; we’d all be better able to inhabit it with even a slightly clearer idea of how it did so. Visit the Historical Tech Tree here.

but a sense of how much of that knowledge we lack. Our civilization has made its way from stone tools to robotaxis, mRNA vaccines, and LLM chatbots; we’d all be better able to inhabit it with even a slightly clearer idea of how it did so. Visit the Historical Tech Tree here.

Related content:

An Interactive Timeline Covering 14 Billion Years of History: From The Big Bang to 2015

The Tree of Languages Illustrated in a Big, Beautiful Infographic

The History of Philosophy Visualized

The History of Modern Art Visualized in a Massive 130-Foot Timeline

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.