Image via Wikimedia Commons

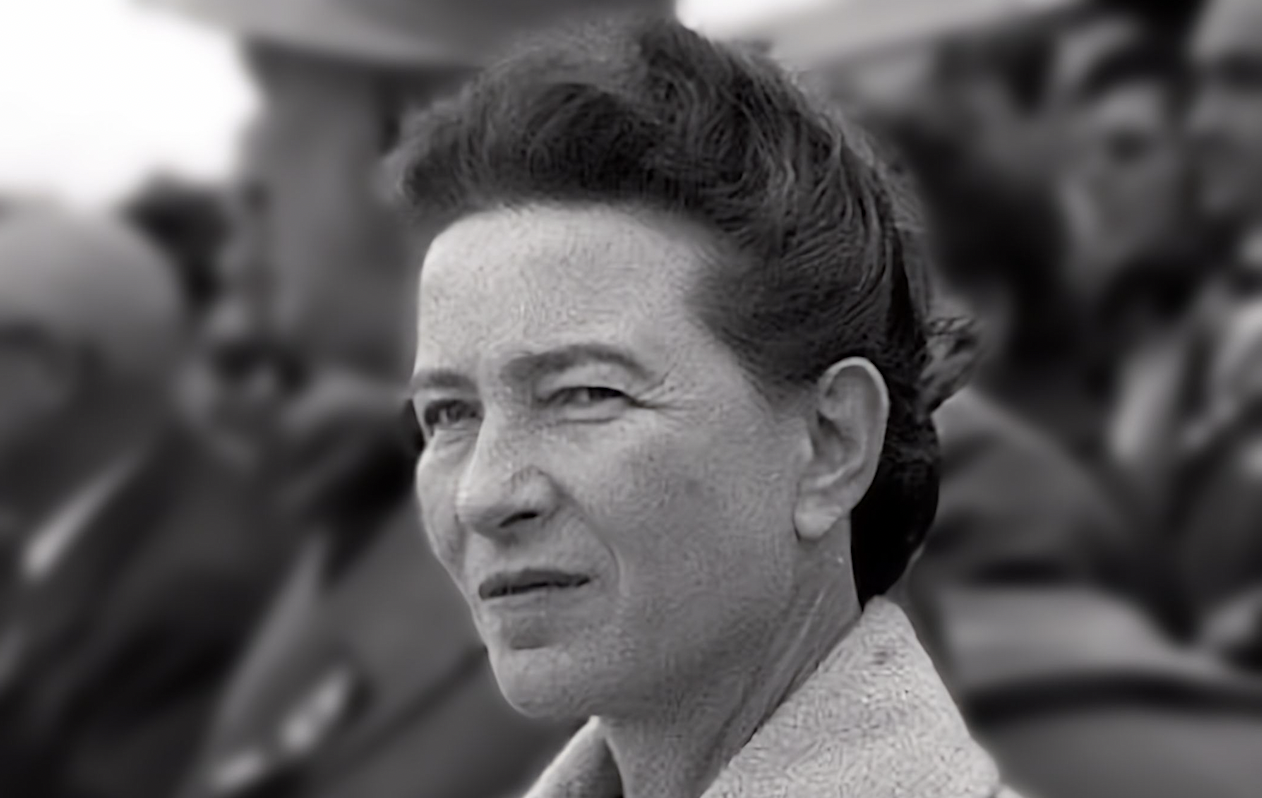

In the legend of the Buddha, prince Siddhartha encounters the poor souls outside his palace walls and sees, for the first time, the human condition: debilitating illness, aging, death. He is shocked. As Simone de Beauvoir paraphrases in The Coming of Age, her groundbreaking study of the depredations of growing old, Siddhartha wonders, “What is the use of pleasures and delights, since I myself am the future dwelling-place of old age?”

Rather than deny his knowledge of suffering, the Buddha followed its logic to the end. “In this,” de Beauvoir writes ironically, “he differed from the rest of mankind… being born to save humanity.” We are mostly out to save ourselves – or our stubborn ideas of who we should be. The more wealth and power we have, the easier it may be to fight the transformations of age…. Until we cannot, since “growing, ripening, aging, dying – the passing of time is predestined.”

When she began to write about her own aging, de Beauvoir was besieged, she says, by “great numbers of people, particularly old people [who] told me, kindly or angrily but always at great length and again and again, that old age simply did not exist!” The hundreds and thousands of dollars spent to fight nature’s effect on our appearance only serves to “prolong,” she writes, our “dying youth.”

Obsessions with cosmetics and cosmetic surgery come from an ageism imposed from without by what scholar Kathleen Woodward calls “the youthful structure of the look” — a harsh gaze that turns the old into “The Other.” The aged are subject to a “stigmatizing social judgment, made worse by our internalization of it.” Ram Dass summarized the condition in 2019 by saying we live in “a very cruel culture” — an “aging society… with a youth mythology.”

The contradictions can be stark. Many of Ram Dass’ generation have become valuable fodder in marketing and politics for their reliability as voters or consumers, a major shift since 1972. But, for all the focus on baby boomers as a hated or a useful demographic, they are largely invisible outside of a certain wealthy class. Old age in the West is no less fraught with economic and social precarity than when de Beauvoir wrote.

De Beauvoir movingly describes conditions that were briefly evident in the media during the worst of the pandemic – the isolation, fear, and marginalization that older people face, especially those without means. “The presence of money cannot always alleviate” the pains of aging, wrote Elizabeth Hardwick in her 1972 review of de Beauvoir’s book in translation. “Its absence is a certain catastrophe.”

The problem, de Beauvoir pointed out, is that old age is almost synonymous with poverty. The elderly are deemed unproductive, unprofitable, a burden on the state and family. She quotes a Cambridge anthropologist, Dr. Leach, who stated at a conference, “in effect, ‘In a changing world, where machines have a very short run of life, men must not be used too long. Everyone over fifty-five should be scrapped.’”

The sentiment, expressed in 1968, sounds not unlike a phrase bandied around by business analysts thanks to Erik Brynjolkfsson’s call for human beings to “race with the machines.” It is, eventually, a race everyone loses. And the push for profitability over human flourishing comes back to haunt us all.

We carry this ostracism so far that we even reach the point of turning it against ourselves: for in the old person that we must become, we refuse to recognize ourselves.”

De Beauvoir’s response to the widespread cultural denial of aging was to write the first full-length philosophical study of aging in existence, “to break the conspiracy of silence,” she proclaimed. First published as La vieillesse in 1970, the book dared tread where no scholar or thinker had, as Woodward writes in a 2016 re-appraisal:

The Coming of Age is the inaugural and inimitable study of the scandalous treatment of aging and the elderly in today’s capitalist societies…. There was no established method or model for the study of aging. Beauvoir had to invent a way to pursue this enormous subject. What did she do? …. She surveyed and synthesized what she had found in multiple domains, including biology, anthropology, philosophy, and the historical and cultural record, drawing it all together to argue with no holds barred that the elderly are not only marginalized in contemporary capitalist societies, they are dehumanized.

The book is just as relevant in its major points, argues professor of philosophy Tove Pettersen, despite some sweeping generalizations that may not hold up now or didn’t then. But the exclusions suffered by aging women in capitalist societies are still especially cruel, as the philosopher argued. Women are still stigmatized for their desires after menopause and ceaselessly judged on their appearance at all times.

De Beauvoir’s study has been compared to the exhaustive work of Michel Foucault, who excavated such human conditions as madness, sexuality, and punishment. And like his studies, it can feel claustrophobic. Is there any way out of being Othered, pushed aside, and ignored by the next generation as we age? “Beauvoir claims that the oppressed are not always just passive victims,” says Pettersen, “and that not all oppression is total.”

We may be conditioned to see aging people as no longer useful or desirable, and to see ourselves that way as we age. But to wholly accept the logic of this judgment is to allow old age to become a “parody” of youth, writes de Beauvoir, as we chase after the past in misguided efforts to reclaim lost social status. We must resist the backward look that a youth-obsessed culture encourages by allowing ourselves to become something else, with a focus turned outward toward a future we won’t see.

As an old Zen master once pointed out, the leaves don’t go back on the tree. The leaves in fall and the tree in winter, however, are things of beauty and promise:

There is only one solution if old age is not to be an absurd parody of our former life, and that is to go on pursuing ends that give our existence a meaning — devotion to individuals, to groups or to causes, social, political, intellectual or creative work… In old age we should wish still to have passions strong enough to prevent us turning in on ourselves. One’s life has value so long as one attributes value to the life of others, by means of love, friendship, indignation, compassion.

Borrow de Beauvoir’s The Coming of Age from the Internet Archive and read it online for free. Or purchase a copy of your own.

Related Content:

Ram Dass (RIP) Offers Wisdom on Confronting Aging and Dying

Life Lessons From 100-Year-Olds: Timeless Advice in a Short Film

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness