Paul Klee led an artistic life that spanned the 19th and 20th centuries, but he kept his aesthetic sensibility tuned to the future. Because of that, much of the Swiss-German Bauhaus-associated painter’s work, which at its most distinctive defines its own category of abstraction, still exudes a vitality today.

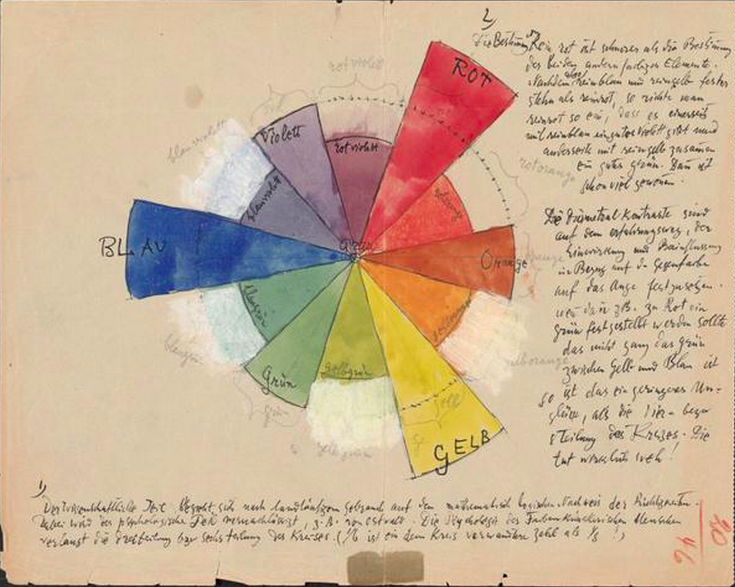

And he left behind not just those 9,000 pieces of art (not counting the hand puppets he made for his son), but plenty of writings as well, the best known of which came out in English as Paul Klee Notebooks, two volumes (The Thinking Eye and The Nature of Nature) collecting the artist’s essays on modern art and the lectures he gave at the Bauhaus schools in the 1920s.

“These works are considered so important for understanding modern art that they are compared to the importance that Leonardo’s A Treatise on Painting had for Renaissance,” says Monoskop. Their description also quotes critic Herbert Read, who described the books as “the most complete presentation of the principles of design ever made by a modern artist – it constitutes the Principia Aesthetica of a new era of art, in which Klee occupies a position comparable to Newton’s in the realm of physics.”

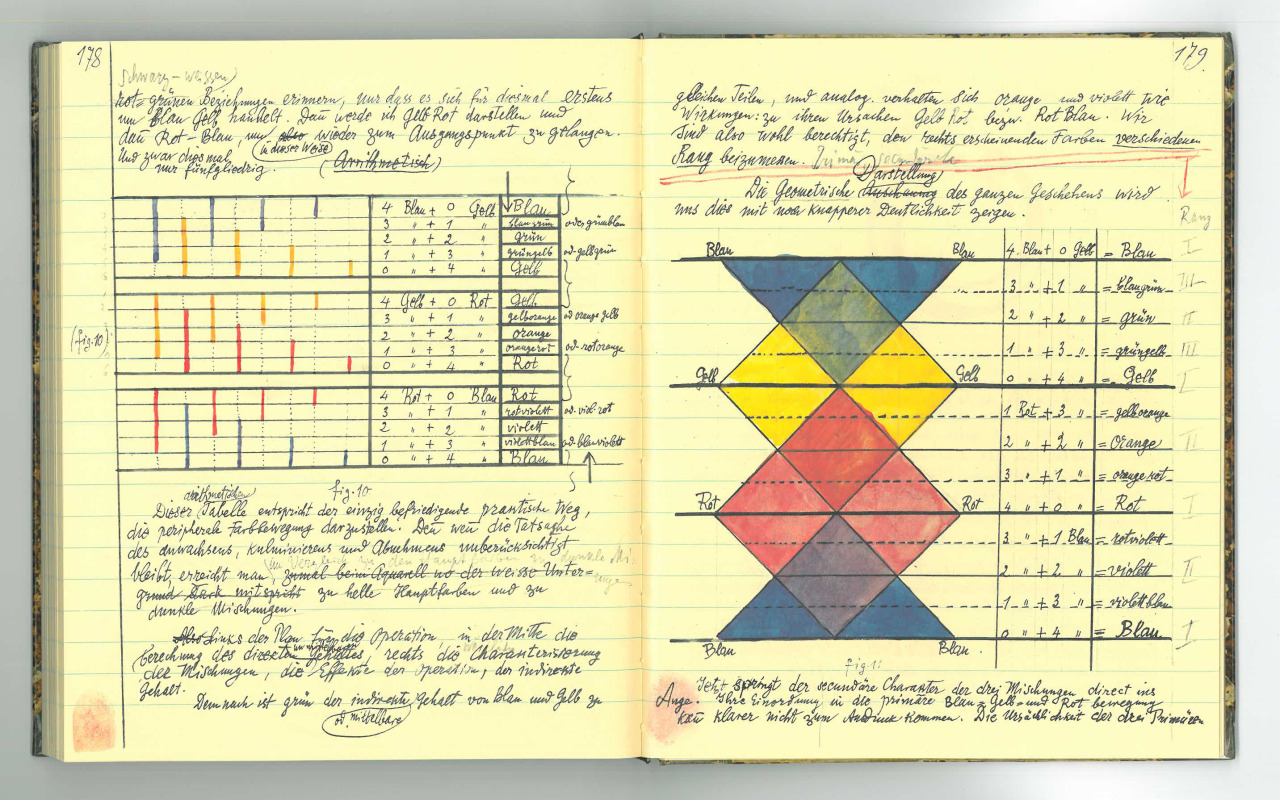

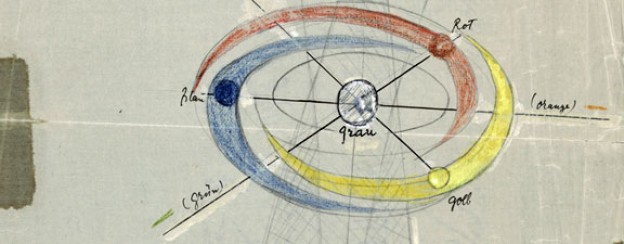

More recently, the Zentrum Paul Klee made available online almost all 3,900 pages of Klee’s personal notebooks, which he used as the source for his Bauhaus teaching between 1921 and 1931. If you can’t read German, his extensively detailed textual theorizing on the mechanics of art (especially the use of color, with which he struggled before returning from a 1914 trip to Tunisia declaring, “Color and I are one. I am a painter”) may not immediately resonate with you. But his copious illustrations of all these observations and principles, in their vividness, clarity, and reflection of a truly active mind, can still captivate anybody — just as his paintings do.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2016.

Related Content:

The Homemade Hand Puppets of Bauhaus Artist Paul Klee

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.