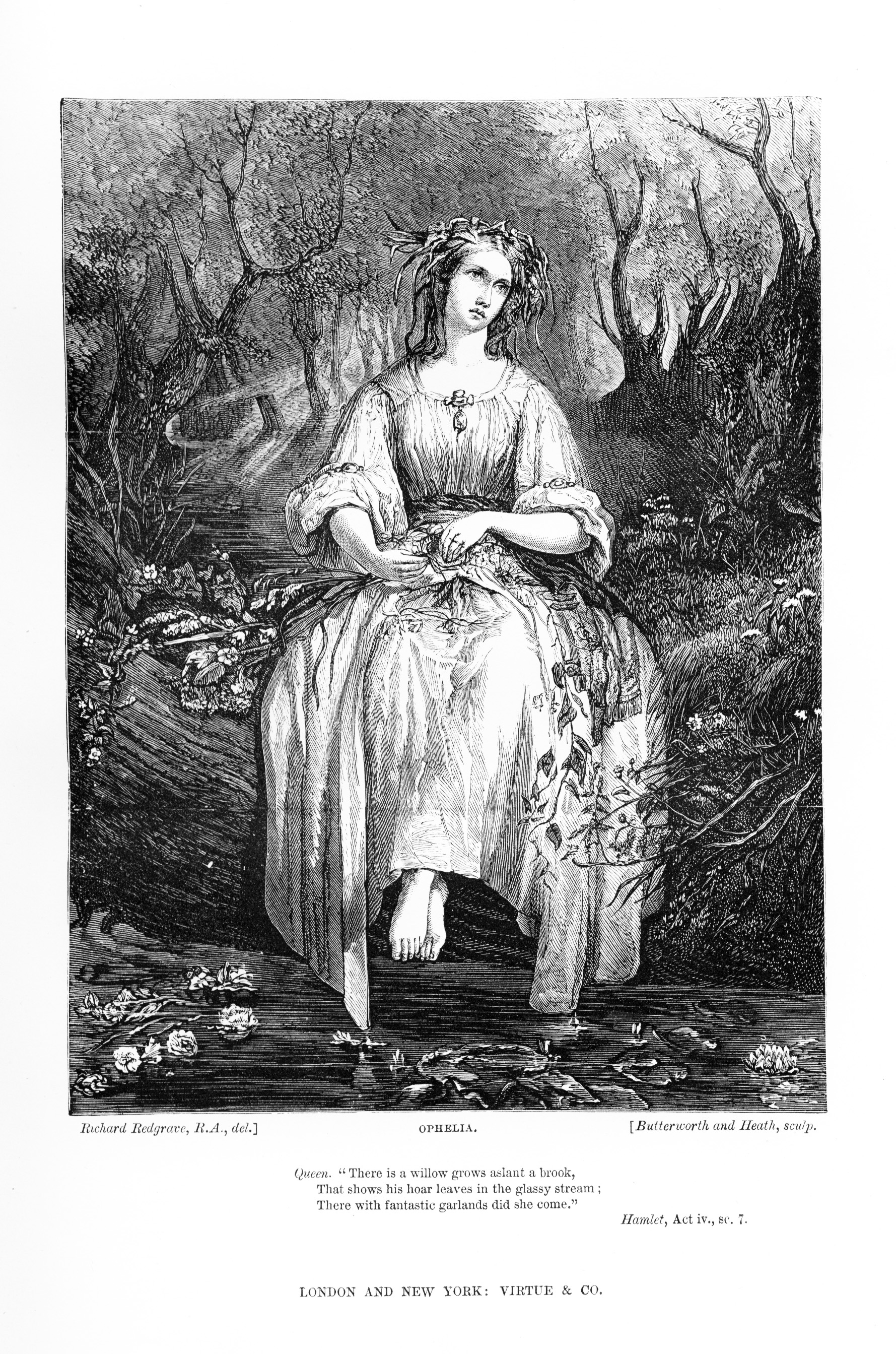

In the graduate department where I once taught freshmen and sophomores the rudiments of college English, it became common practice to include Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus on many an Intro to Lit syllabus, along with a viewing of Julie Taymor’s flamboyant film adaptation. The early work is thought to be Shakespeare’s first tragedy, cobbled together from popular Roman histories and Elizabethan revenge plays. And it is a truly bizarre play, swinging wildly in tone from classical tragedy, to satirical dark humor, to comic farce, and back to tragedy again. Critic Harold Bloom called Titus “an exploitative parody” of the very popular revenge tragedies of the time—its murders, maimings, rapes, and mutilations pile up, scene upon scene, and leave characters and readers/audiences reeling in grief and disbelief from the shocking body count.

Part of the fun of teaching Titus is in watching students’ jaws drop as they realize just how bloody-minded the Bard is. While Taymor’s adaptation takes many modern liberties in costuming, music, and set design, its horror-show depiction of Titus’ unrelenting mayhem is faithful to the text. Later, more mature plays rein in the excessive black comedy and shock factor, but the bodies still stack up. As accustomed as we are to thinking of contemporary entertainments like Game of Thrones as especially gratuitous, the whole of Shakespeare’s corpus, writes Alice Vincent at The Telegraph, is “more gory” than even HBO’s squirm-worthy fantasy epic, featuring a total of 74 deaths in 37 plays to Game of Thrones’ 61 in 50 episodes.

All of those various demises came together in a 2016 compendium staged at The Globe (in London) called The Complete Deaths. It included everything “from early rapier thrusts to the more elaborate viper-breast application adopted by Cleopatra.” The only death director Tim Crouch excluded is “that of a fly that meets a sticky end in Titus Andronicus.” In the infographic above, see all of the causes of those deaths, including Antony and Cleopatra’s snakebite and Titus Andronicus’ piece-de-resistance, “baked in a pie.”

Part of the reason so many of my former undergraduate students found Shakespeare’s brutality shocking and unexpected has to do with the way his work was tamed by later 17th and 18th century critics, who “didn’t approve of the on-stage gore.” The Telegraph quotes director of the Shakespeare Institute Michael Dobson, who points out that Elizabethan drama was especially gruesome; “the English drama was notorious for on-stage deaths,” and all of Shakespeare’s contemporaries, including Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson, wrote violent scenes that can still turn our stomachs.

More recent productions like a bloody staging of Titus at The Globe have restored the gore in Shakespeare’s work, and The Complete Deaths left audiences with little doubt that Shakespeare’s culture was as permeated with representations of violence as our own—and it was as much, if not more so, plagued by the real thing.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2016.

Related Content:

Take a Virtual Tour of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in London

Hear What Shakespeare Sounded Like in the Original Pronunciation

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC.