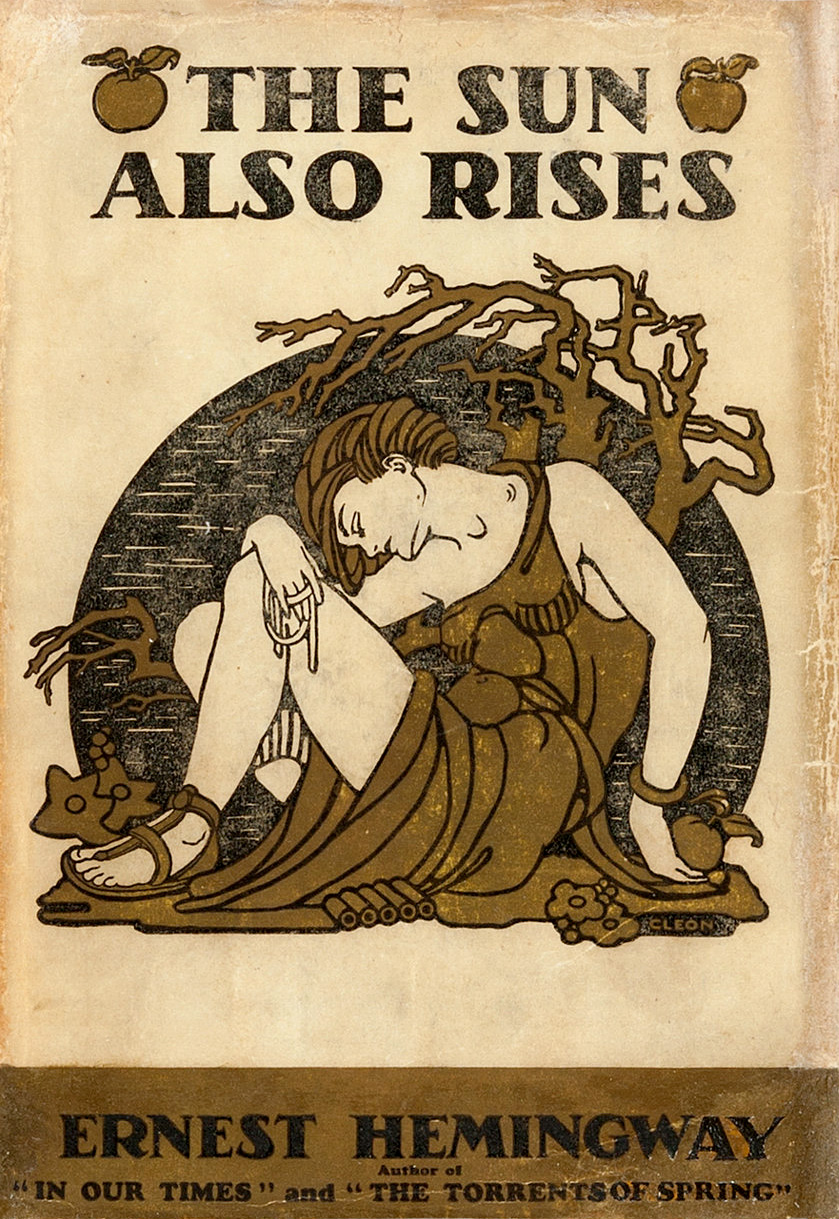

Ernest Hemingway “made the English language new, changed the rhythms of the way both his own and the next few generations would speak and write and think. The very grammar of a Hemingway sentence dictated, or was dictated by, a certain way of looking at the world, a way of looking but not joining, a way of moving through but not attaching, a kind of romantic individualism distinctly adapted to its time and source.” So writes the late Joan Didion, a writer hardly without influence herself, in a 1998 reflection on the author of such novels as A Farewell to Arms, For Whom the Bell Tolls, and The Old Man and the Sea.

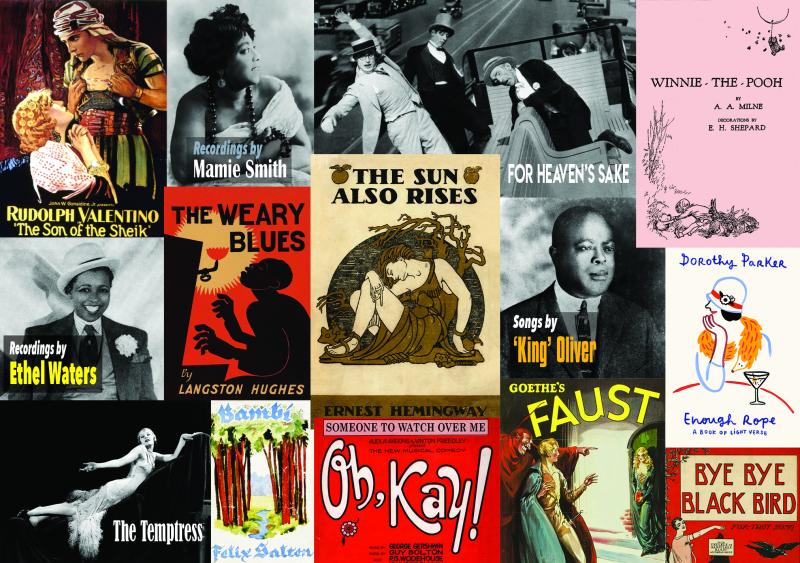

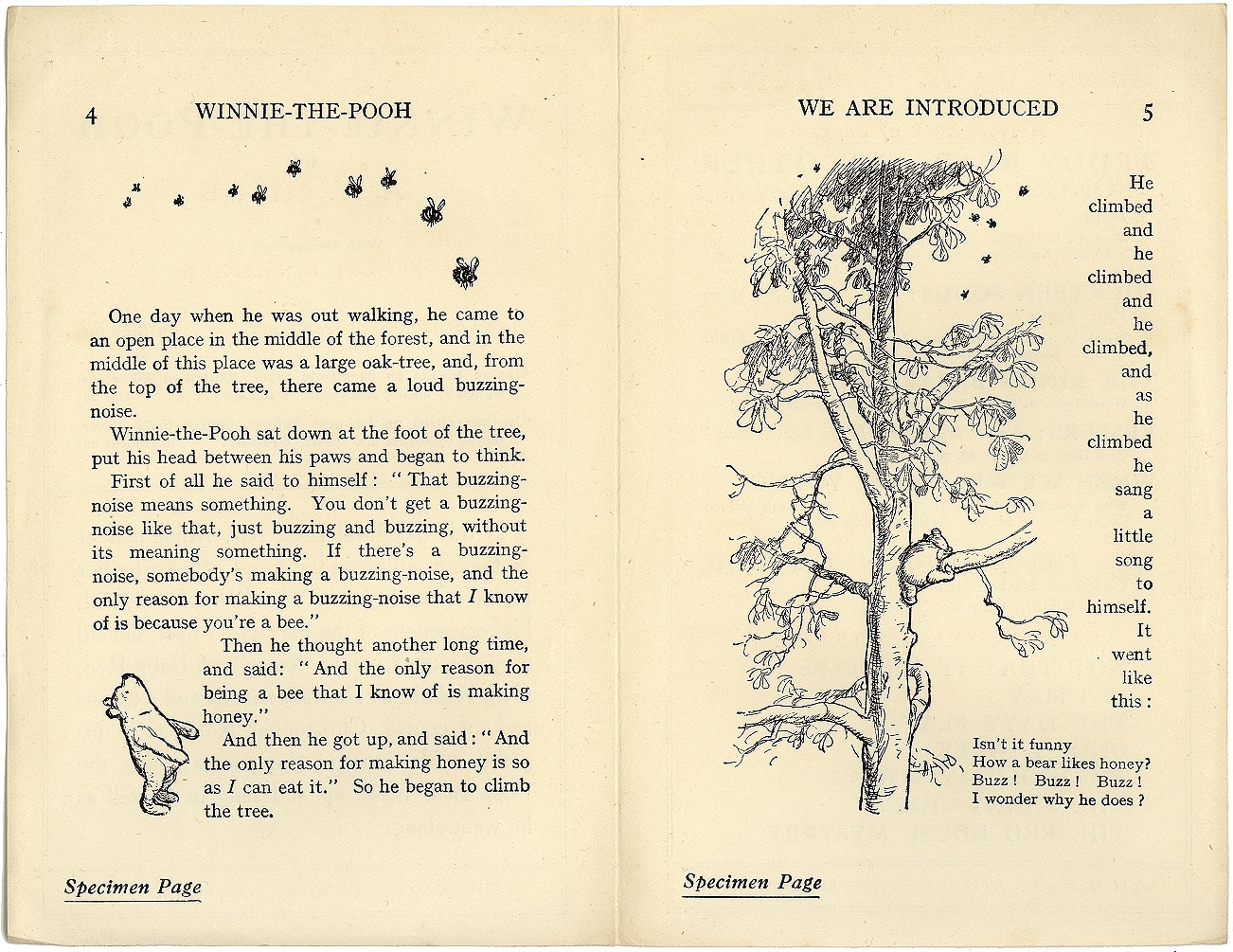

The literary phenomenon that was Hemingway began in earnest, as it were, with The Sun Also Rises. Having been published in 1926, his first full-length novel now stands on the brink of the public domain. So do a variety of other works that launched storied careers: William Faulkner’s first novel Soldiers’ Pay, for instance, or A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh, which introduced the now-beloved titular bear to the reading public. Having celebrated his 90th anniversary back in 2016 with the addition of a new penguin character to the Hundred Acre Wood, Winnie-the-Pooh remains the core of what has developed into a formidable cultural industry.

The work of Hemingway, too, has inspired no small amount of commercial enterprise. (Didion writes of Thomasville Furniture Industries’ new “Ernest Hemingway Collection,” whose themes include “Kenya,” “Key West,” “Havana,” and “Ketchum.”) But now that work itself has begun to come legally available to all, free of charge: “anyone can rescue them from obscurity and make them available, where we can all discover, enjoy, and breathe new life into them.”

So writes Jennifer Jenkins, Director of Duke’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain, in her post on Public Domain Day 2022. In it she names a host of other 1926 books similarly set for liberation, including Langston Hughes’ The Weary Blues, T. E. Lawrence’s The Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, and H. L. Mencken’s Notes on Democracy.

The deeper we get into the 21st century, the wider the variety of media that falls into the public domain. Jenkins highlights silent-film comedies like For Heaven’s Sake with Harold Lloyd and Battling Butler with Buster Keaton, as well — the mid-1920s having seen the dawn of the “talkie” — as sound pictures like Don Juan, the “first feature-length film to use the Vitaphone sound system.” Unlike in previous years, a large number of not just musical compositions but actual sound recordings will also come available for free reuse. These include records by jazz and blues singer Ethel Waters, operatic tenor Enrico Caruso, cellist Pablo Casals, and composer-pianist Sergei Rachmaninoff. And as for those waiting to reuse the work of Joan Didion, rest assured that The White Album will be yours on Public Domain Day 2091.

On a related note, the Public Domain Review has a nice post overviewing the sound recordings entering the public domain in ’22.

Related Content:

Ernest Hemingway’s Very First Published Stories, Free as an eBook

Hear the Classic Winnie-the-Pooh Read by Author A.A. Milne in 1929

Watch the Great Russian Composer Sergei Rachmaninoff in Home Movies

The Public Domain Project Makes 10,000 Film Clips, 64,000 Images & 100s of Audio Files Free to Use

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.