In our experience, bird lovers fall into two general categories:

Keenly observant cataloguers like John James Audubon …

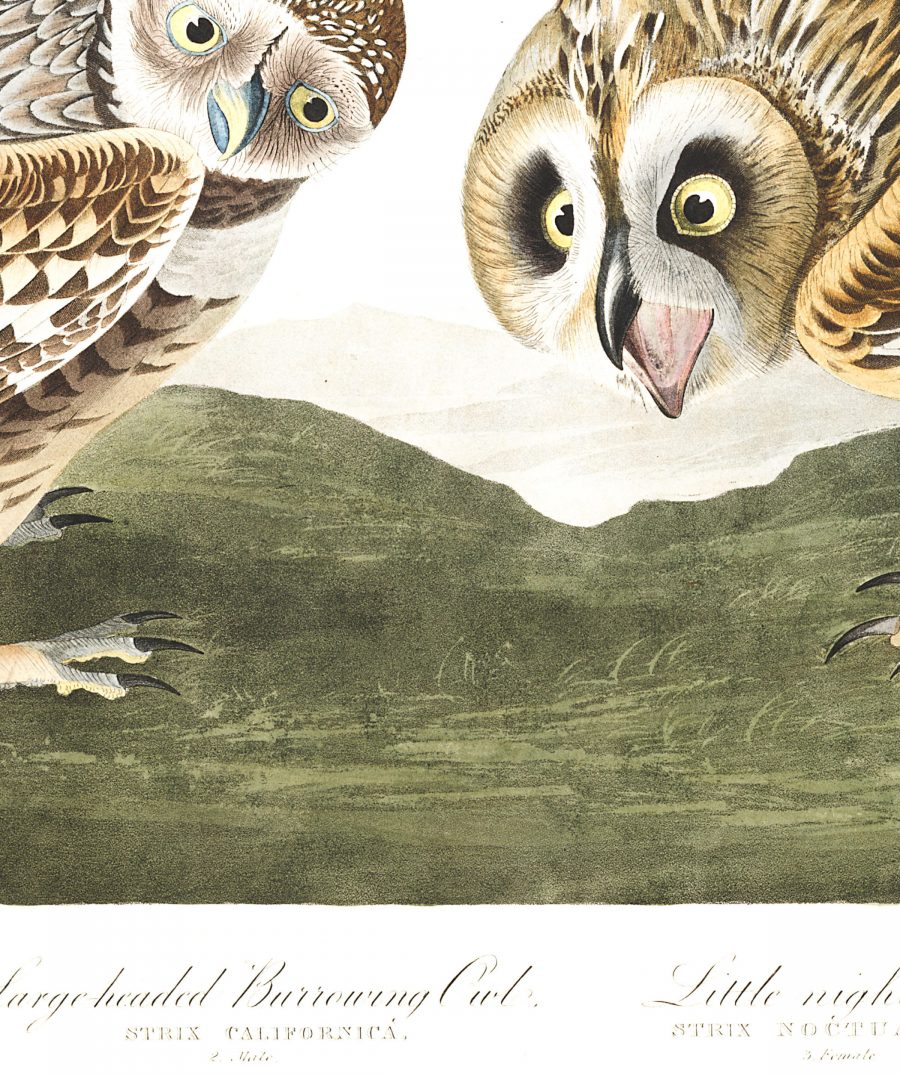

And those of us who cannot resist assigning anthropomorphic personalities and behaviors to the 435 stars of Audubon’s The Birds of America, a stunning collection of prints from life-size watercolors he produced between 1827 and 1838.

Our suspicions have little to do with biology, but rather, a certain zestiness of expression, an overemphatic beak, a droll gleam in the eye.

The Audubon Society’s newly redesigned website abounds with treasure for those in either camp:

Free high res downloads of all 435 plates.

Mp3s of each specimen’s call.

And vintage commentary that effectively splits the difference between science and the unintentionally humorous locutions of another age.

Take for instance, the Burrowing Owl, as described by self-taught naturalist Thomas Say (1787–1834):

It is delightful, during fine weather, to see these lively little creatures sporting about the entrance of their burrows, which are always kept in the neatest repair, and are often inhabited by several individuals. When alarmed, they immediately take refuge in their subterranean chambers; or, if the dreaded danger be not immediately impending, they stand near the brink of the entrance, bravely barking and flourishing their tails, or else sit erect to reconnoitre the movements of the enemy.

The notes of ornithologist John Kirk Townsend (1809 – 1851) suggest that not everyone was as taken with the species as Say (who was, in all fairness, the father of American entomology):

Nothing can be more unpleasant than the bagging of this species, on account of the fleas with which their plumage swarms, and which in all probability have been left in the burrow by the Badger or Marmot, at the time it was abandoned by these animals. I know of no other bird infested by that kind of vermin.

The Common Gallinule, above, suggests that there’s often more to these birds than meets the eye. His somewhat sheepish looking countenance belies the red hot love life Audubon recounts:

… the manifestations of their amatory propensity were quite remarkable. The male birds courted the females, both on the land and on the water; they frequently spread out their tail like a fan, and moved round each other, emitting a murmuring sound for some seconds. The female would afterwards walk to the water’s edge, stand in the water up to her breast, and receive the caresses of the male, who immediately after would strut on the water before her, jerking with rapidity his spread tail for awhile, after which they would both resume their ordinary occupations.

Being that we are firmly planted in the second type of bird lover’s camp, this ornithological cornucopia mainly serves to whet our appetite for more Falseknees, self-described bird nerd Joshua Barkman’s beautifully rendered webcomic.

Yes, Audubon’s Indigo Bird, aka Petit Papebleu, “an active and lively little fellow” who “possesses much elegance in his shape, and also a certain degree of firmness in his make” was separated by a century or so from “Mood Indigo”—we presume that’s the tune stuck in Barkman’s bird’s head—but he does look rather preoccupied, no?

Possibly just thinking of mealworms…

Explore Audubon’s Birds of America by chronological or alphabetical order, or by state, and download them all for free here.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2019.

Related Content:

What Kind of Bird Is That?: A Free App From Cornell Will Give You the Answer

The Bird Library: A Library Built Especially for Our Fine Feathered Friends

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and theater maker in NYC.