Step right up, folks!

Thrill to the Fire and Flames show!

See the Bearded Lady!

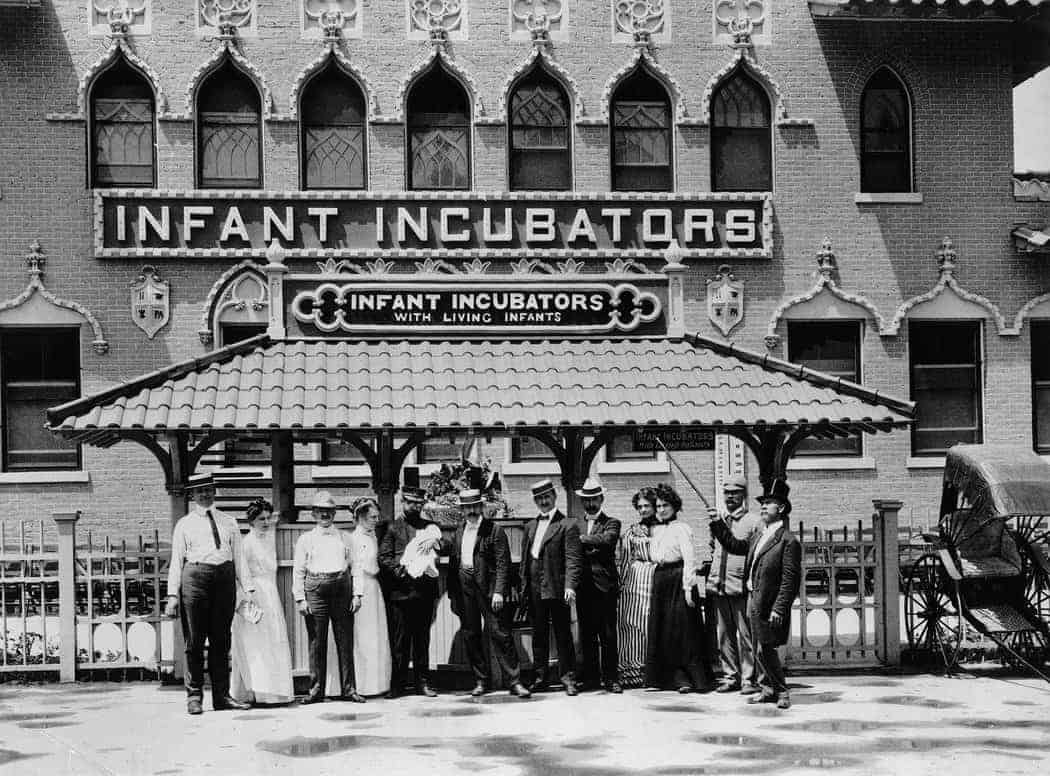

Early in the 20th century, crowds flocked to New York City’s Coney Island, where wonders awaited at every turn.

In 1902, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle published a few of the highlights in store for visitors at Coney Island’s soon-to-open “electric Eden,” Luna Park:

…the most important will be an illustration of Jules Verne’s ‘Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea’, which will cover 55,000 square feet of ground, and a naval spectatorium, which will have a water area of 60,000 square feet. Beside these we will have many novelties, including the River Styx, the Whirl of the Town, Shooting the White Horse Rapids, the Grand Canyon, the ’49 Mining Camp, Dragon Rouge, overland and incline railways, Japanese, Philippine, Irish, Eskimo and German villages, the infant incubator, water show and carnival, circus and hippodrome, Yellowstone Park, zoological gardens, performing wild beasts, sea lions and seals, caves of Capri, the Florida Everglades and Mont Pelee, an electric representation of the volcanic destruction of St. Pierre.

Hold up a sec…what’s this about an infant incubator? What kind of name is that for a roller coaster!?

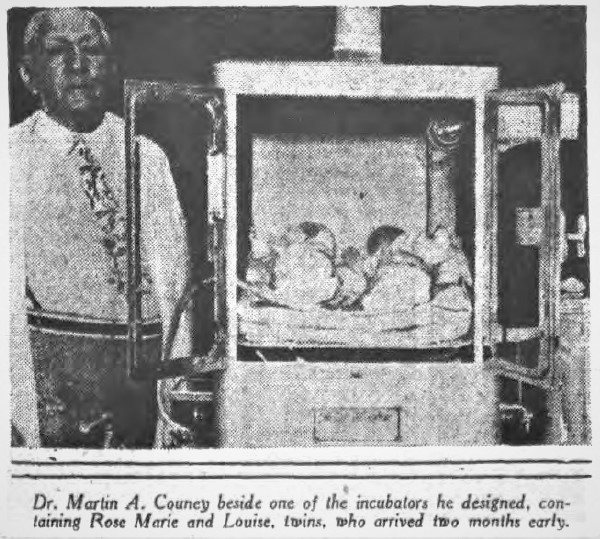

As it turns out, amid all the exotica and bedazzlements, a building furnished with steel and glass cribs, heated from below by temperature-controlled hot water pipes, was one of the boardwalk’s leading attractions.

Antiseptic-soaked wool acted as a rudimentary air filter, while an exhaust fan kept things properly ventilated.

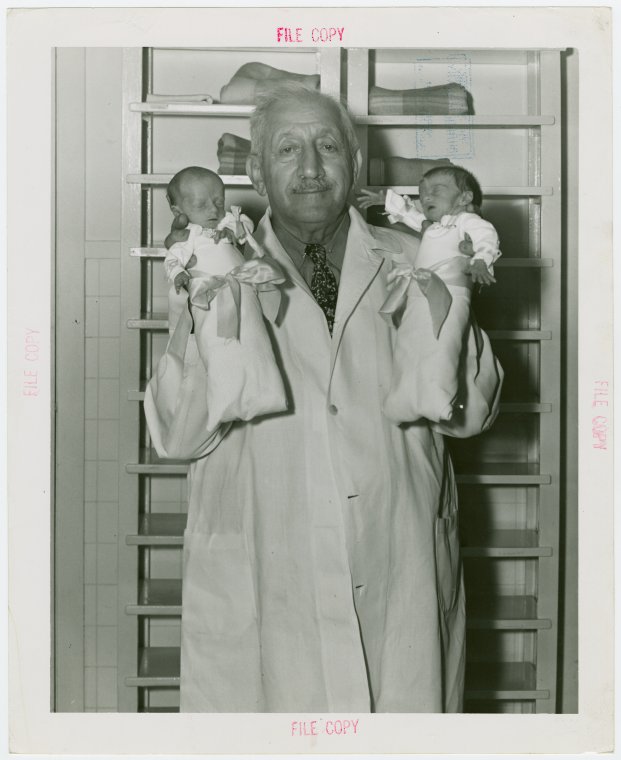

The real draw were the premature babies who inhabited these cribs every summer, tended to round the clock by a capable staff of white clad nurses, wet nurses and Dr. Martin Couney, the man who had the ideas to put these tiny newborns on display…and in so doing, saved thousands of lives.

Couney, a breast feeding advocate who once apprenticed under the founder of modern perinatal medicine, obstetrician Pierre-Constant Budin, had no license to practice.

Nor did he have an md.

Initially painted as a child-exploiting charlatan by many in the medical community, he was as vague about his background as he was passionate about his advocacy for preemies whose survival depended on robust intervention.

Having presented Budin’s Kinderbrutanstalt — child hatchery — to spectators at 1896’s Great Industrial Exposition of Berlin, and another infant incubator show as part of Queen Victoria Diamond Jubilee Celebration, he knew firsthand the public’s capacity to become invested in the preemies’ welfare, despite a general lack of interest on the part of the American medical establishment.

Thusly was the idea for the boardwalk Infantoriums hatched.

Claire Prentice, author of Miracle at Coney Island: How a Sideshow Doctor Saved Thousands of Babies and Transformed American Medicine, writes that “many doctors at the time held the view that premature babies were genetically inferior ‘weaklings’ whose fate was a matter for God.”

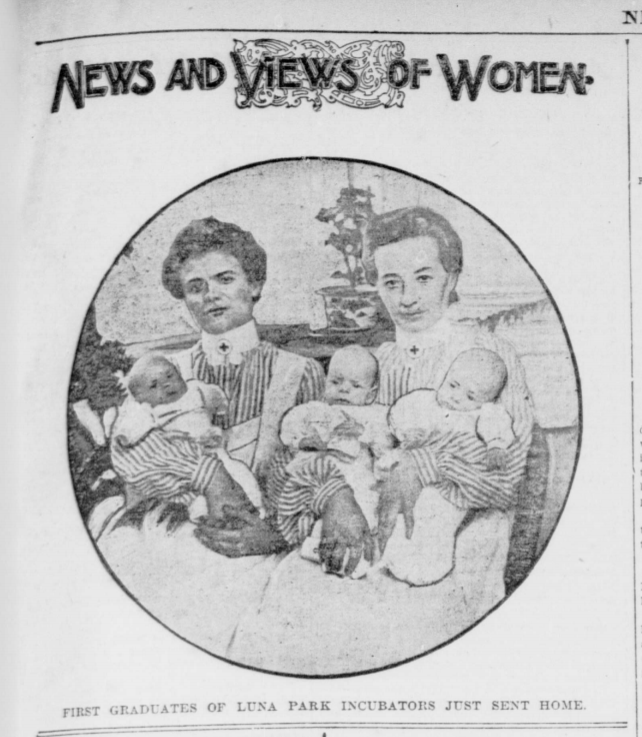

As word of Couney’s Infantorium spread, parents brought their premature newborns to Coney Island, knowing that their chances of finding a lifesaving incubator there was far greater than it would be in the hospital. And the care there would be both highly skilled and free, underwritten by paying spectators who observed the operation through a glass window. Prentice notes that “Couney took in babies from all backgrounds, regardless of race or social class:”

… a remarkably progressive policy, especially when he started out. He did not take a penny from the parents of the babies. In 1903 it cost around $15 (equivalent to around $405 today) a day to care for each baby; Couney covered all the costs through the entrance fees.

The New Yorker’s A. J. Liebling observed Couney at the 1939 World’s Fair in Flushing, Queens, where he had set up in a pink-and-blue building that beckoned visitors with a sign declaring “All the World Loves a Baby:”

The backbone of Dr. Couney’s business is supplied by the repeaters. A repeater becomes interested in one baby and returns at intervals of a week or less to note its growth. Repeaters attend more assiduously than most of the patients’ parents, even though the parents get in on passes. After a preemie graduates, a chronic repeater picks out another one and starts watching it. Dr. Couney’s prize repeater, a Coney Island woman named Cassatt, visited his exhibit there once a week for thirty-six seasons. Repeaters, as one might expect, are often childless married people, but just as often they are interested in babies because they have so many children of their own. “It works both ways,” says Dr. Couney, with quiet pleasure.

It’s estimated that Couney’s incubators spared the lives of more than 6,500 premature babies in the United States, London, Paris, Mexico and Brazil.

Despite his lack of bonafides, a number of pediatricians who toured Couney’s infantoriums were impressed by what they saw, and began referring patients whose families could not afford to pay for medical care. Many, as Liebling reported in 1939, wished his boardwalk attraction could stay open year round, “for the benefit of winter preemies:”

In the early years of the century no American hospital had good facilities for handling prematures, and there is no doubt that every winter many babies whom Dr. Couney could have saved died. Even today it is difficult to get adequate care for premature infants in a clinic. Few New York hospitals have set up special departments for their benefit, because they do not get enough premature babies to warrant it; there are not enough doctors and nurses experienced in this field to go around. Care of prematures as private patients is hideously expensive. One item it involves is six dollars a day for mother’s milk, and others are rental of an incubator and hospital room, oxygen, several visits a day by a physician, and fifteen dollars a day for three shifts of nurses. The New York hospitals are making plans now to centralize their work with prematures at Cornell Medical Center, and probably will have things organized within a year. When they do, Dr. Couney says, he will retire. He will feel he has “made enough propaganda for preemies.”

Listen to a StoryCorps interview with Lucille Horn, a 1920 graduate of Couney’s Coney Island incubators below.

Related Content

Why Babies in Medieval Paintings Look Like Middle-Aged Men: An Investigative Video

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. She greeted 2024 with thousands of other New Yorkers, taking a polar bear plunge at Coney Island. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Leave a Reply