Photo by Al Aumuller, via Wikimedia Commons

Like another famous Okie from Muskogee, Woody Guthrie came from a part of Oklahoma that the U.S. government sold during the 1889 land rush away from the Quapaw and Osage nations, as well as the Muscogee, a people who had been forcibly relocated from the Southeast under Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act. By the time of Guthrie’s birth in 1912 in Okfuskee County, next to Muskogee, the region was in the hands of conservative Democrats like Guthrie’s father Charles, a landowner and member of the revived KKK who participated in a brutal lynching the year before Guthrie was born.

Guthrie was named after president Woodrow Wilson, who was highly sympathetic to Jim Crow (but perhaps not, as has been alleged, an admirer of the Klan). While he inherited many of his father’s attitudes, he reconsidered them to such a degree later in life that he wrote a song denouncing the notoriously racist New York landlord Fred Trump, father of the current president. “By the time he moved into his new apartment” in Brooklyn in 1950, writes Will Kaufman at The Guardian, Guthrie “had traveled a long road from the casual racism of his Oklahoma youth.”

Guthrie was deeply embedded in the formative racial politics of the country. While some people may convince themselves that a time in the U.S. past was “great”—unmarred by class conflict and racist violence and exploitation, secure in the hands of a benevolent white majority—Guthrie’s life tells a much more complex story. Many Indigenous people feel with good reason that Guthrie’s most famous song, “The Land is Your Land,” has contributed to nationalist mythology. Others have viewed the song as a Marxist anthem. Like much else about Guthrie, and the country, it’s complicated.

Considered by many, Stephen Petrus writes, “to be the alternative national anthem,” the song “to many people… represents America’s best progressive and democratic traditions.” Guthrie turned the song into a hymn for the struggle against fascism and for the nascent Civil Rights movement. Written in New York in 1940 and first recorded for Moe Asch’s Folkways Records in 1944, “This Land is Your Land” evolved over time, dropping verses protesting private property and poverty after the war in favor of a far more patriotic tone. It was a long evolution from embittered parody of “God Bless America” to “This land was made for you and me.”

But whether socialist or populist in nature, Guthrie’s patriotism was always subversive. “By 1940,” writes John Pietaro, he had “joined forces with Pete Seeger in the Almanac Singers,” who “as a group, joined the Communist Party. Woody’s guitar had, by then, been adorned with the hand-painted epitaph, THIS MACHINE KILLS FASCISTS.” (Guthrie had at least two guitars with the slogan scrawled on them, one on a sticker and one with ragged hand-lettering.) The phrase, claims music critic Jonny Whiteside, was originally “a morale-boosting WWII government slogan printed on stickers that were handed out to defense plant workers.” Guthrie reclaimed the propaganda for folk music’s role in the culture. As Pietaro tells it:

In this time he also founded an inter-racial quartet with Leadbelly, Sonny Terry and Cisco Houston, a veritable super-group he named the Headline Singers. This group, sadly, never recorded. The material must have stood as the height of protest song—he’d named it in opposition to a producer who advised Woody to “stop trying to sing the headlines.” Woody told us that all you can write is what you see.

You can hear The Headline Singers above, minus Lead Belly and featuring Pete Seeger, in the early 1940’s radio broadcast of “All You Fascists Bound to Lose.” “I’m gonna tell you fascists,” sings Woody, “you may be surprised, people in this world are getting organized.” Upon joining the Merchant Marines, Guthrie fought against segregation in the military. After the war, he “stood shoulder to shoulder with Paul Robeson, Howard Fast, and Pete Seeger” against violent racist mobs in Peekskill, New York. Both of Guthrie’s anti-fascist guitars have seemingly disappeared. As Robert Santelli writes, “Guthrie didn’t care for his instruments with much love.” But during the decade of the 1940’s he was never seen without the slogan on his primary instrument.

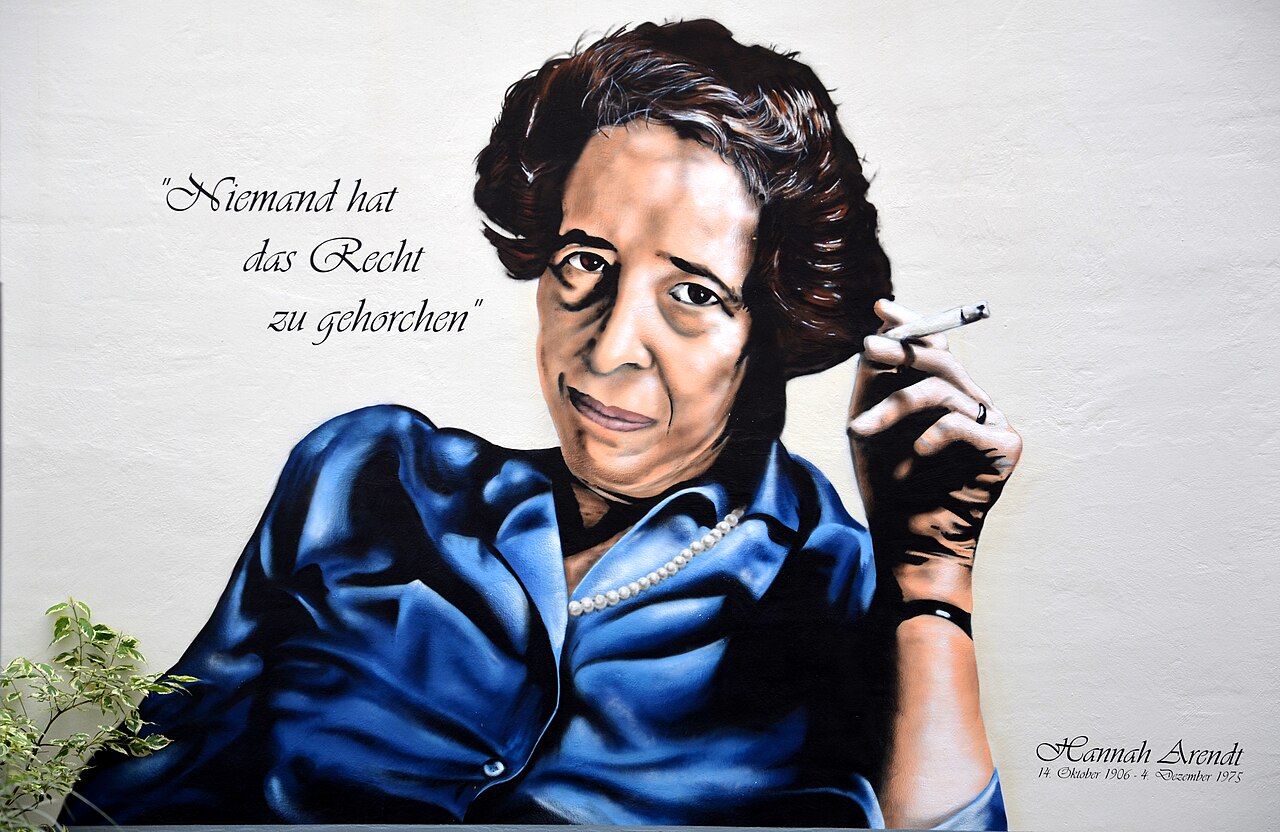

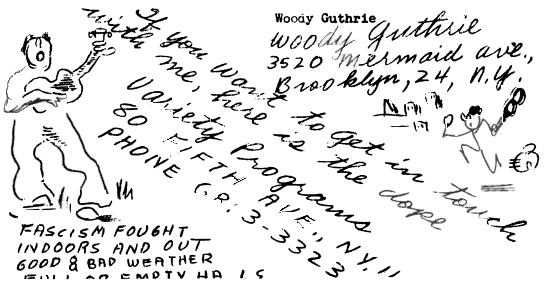

“This Machine Kills Fascists” has since, writes Motherboard, become Guthrie’s “trademark slogan… still referenced in pop culture and beyond” and providing an important point of reference for the anti-fascist punk movement. You can see another of Guthrie’s anti-fascist slogans above, which he scrawled on a collection of his sheet music: “Fascism fought indoors and out, good & bad weather.” Guthrie’s long-lived brother-in-arms Pete Seeger, carried on in the tradition of anti-fascism and anti-racism after Woody succumbed in the last two decades of his life to Huntington’s disease. Like Guthrie, Seeger painted a slogan around the rim of his instrument of choice, the banjo, a message both playful and militant: “This machine surrounds hate and forces it to surrender.”

Photo by “Jim, the Photographer”

Seeger carried the message from his days playing and singing with Guthrie, to his Civil Rights and anti-war organizing and protest in the 50s and 60s, and all the way into the 21st century at Occupy Wall Street in Manhattan in 2011. At the 2009 inauguration of Barack Obama, Seeger sang “This Land is Your Land” onstage with Bruce Springsteen and his son, Tao-Rodriquez Singer. In rehearsals, he insisted on singing the two verses Guthrie had omitted from the song after the war. “So it was,” writes John Nichols at The Nation, “that the newly elected president of the United States began his inaugural celebration by singing and clapping along with an old lefty who remembered the Depression-era references of a song that took a class-conscious swipe at those whose ‘Private Property’ signs turned away union organizers, hobos and banjo pickers.”

Both Guthrie and Seeger drew direct connections between the fascism and racism they fought and capitalism’s outsized, destructive obsession with land and money. They felt so strongly about the battle that they wore their messages figuratively on their sleeves and literally on their instruments. Pete Seeger’s famous banjo has outlived its owner, and the colorful legend around it has been mass-produced by Deering Banjos. Where Guthrie’s anti-fascist guitars went off to is anyone’s guess, but if one of them were ever discovered, Robert Santelli writes, “it surely would become one of America’s most valued folk instruments.” Or one of its most valued instruments in general.

Photo by “Jim, the Photographer”

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2017.

Related Content:

Bruce Springsteen Won’t Back Down: Performs “Streets of Minneapolis” Live in Minneapolis

Hear Two Legends, Lead Belly & Woody Guthrie, Performing on the Same Radio Show (1940)

The Nazis’ 10 Control-Freak Rules for Jazz Performers: A Strange List from World War II

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC.