Next time I make it to Oslo, the National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design ranks high on my to-do list. The next time I make it to Oslo will also count as the first time I make it to Oslo, since the tendency of the city itself to rank high on the world’s-most-expensive places lists (and at the very top of some of those lists) has thus far scared me off of booking a flight there. But if you can handle Oslo’s formidable cost of living, the National Museum’s branches only charge you the equivalent of five bucks or so for admission. And now they’ve offered an even cheaper alternative: 30,000 works of art from their collection, viewable online for free.

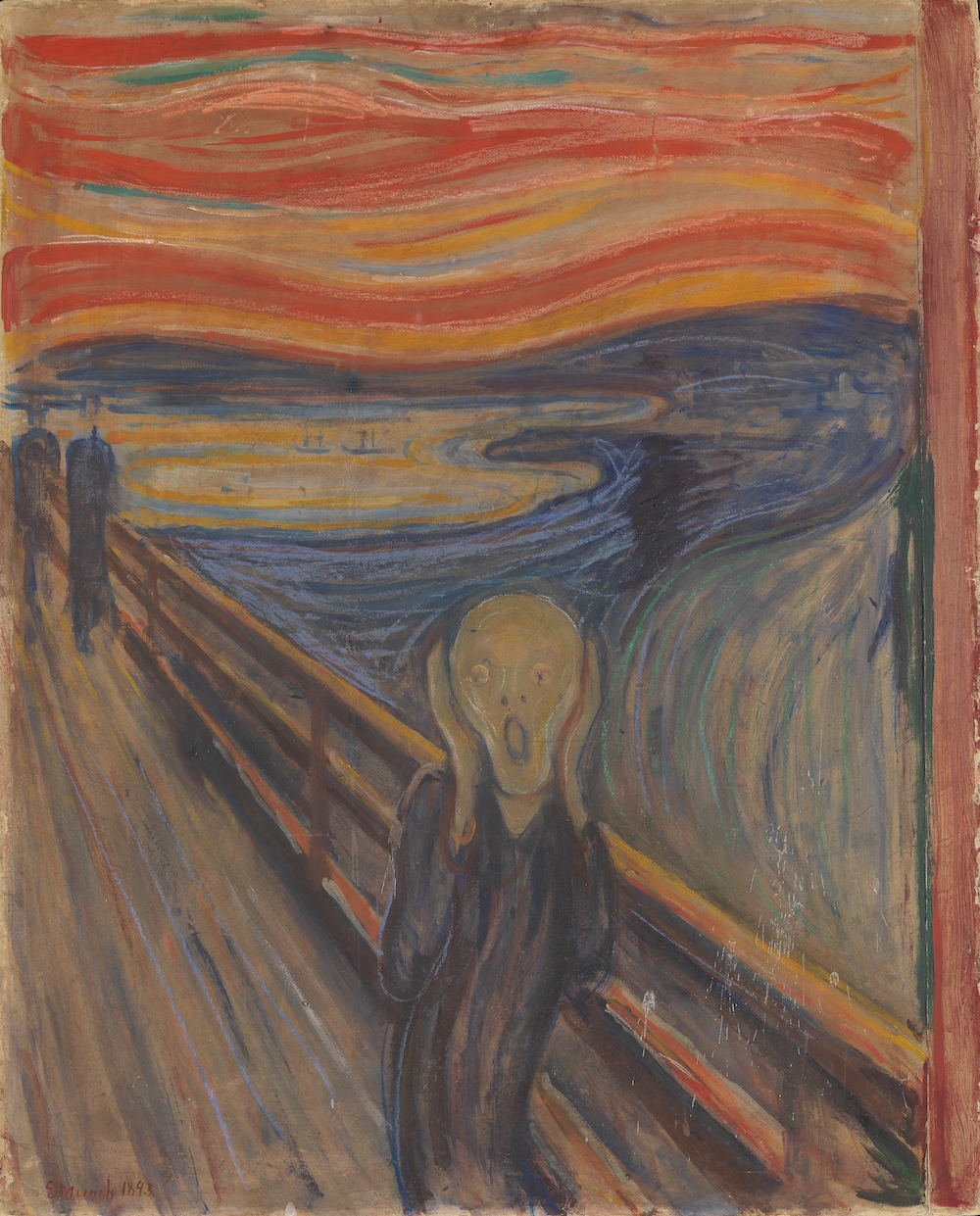

If it all seems overwhelming, you can view the National Museum’s digital collection in sections of highlights: one of pre-1945 works, one of post-1945 works, and one of Edvard Munch. While few of us could confidently call ourselves experts in Norwegian art, all of us know the work of Munch — or at least we know a work of Munch, 1893’s The Scream (Skrik), whose black-garbed central figure, clutching his gaunt features twisted into an expression of pure agony, has gone on to inspire countless homages, parodies, and ironic greeting cards. But Munch, whose career lasted well over half a century and involved printmaking as well as painting, didn’t become Norway’s best-known artist on the strength of The Scream alone.

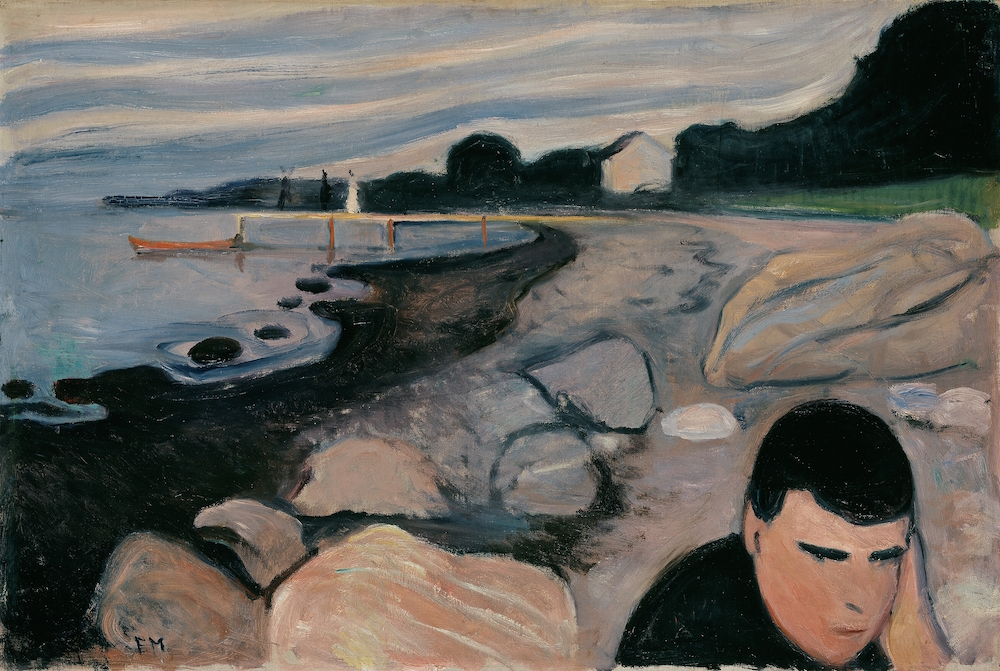

The National Museum’s digital collection offers perhaps your best opportunity to begin to get a sense of the scope of Munch’s art. There you can take an up-close look at (and even download) such pieces as the less agonized Melancholy (Melankoli), painted one year before The Scream; 1901’s The Girls on the Bridge, a more placid treatment of a similar setting; and even, so you can get to know the artist better still, Munch’s 1895 self-portrait with a cigarette. He may not exactly look happy in it, but at least he hasn’t become a visual shorthand for all-consuming pain like the poor fellow he painted on the bridge. (If you want my guess as to what made the subject of The Scream so unhappy, I’d say he just finished looking into average Oslo rents.)

A big thanks to Joakim for making us aware of this collection. If any other readers know of great resources we can feature on the site, please send us a tip here.

Related Content:

Edvard Munch’s Famous Painting The Scream Animated to the Sound of Pink Floyd’s Primal Music

The Guggenheim Puts Online 1600 Great Works of Modern Art from 575 Artists

Rijksmuseum Digitizes & Makes Free Online 210,000 Works of Art, Masterpieces Included!

Download 100,000 Free Art Images in High-Resolution from The Getty

Colin Marshall writes elsewhere on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, and the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future? Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.