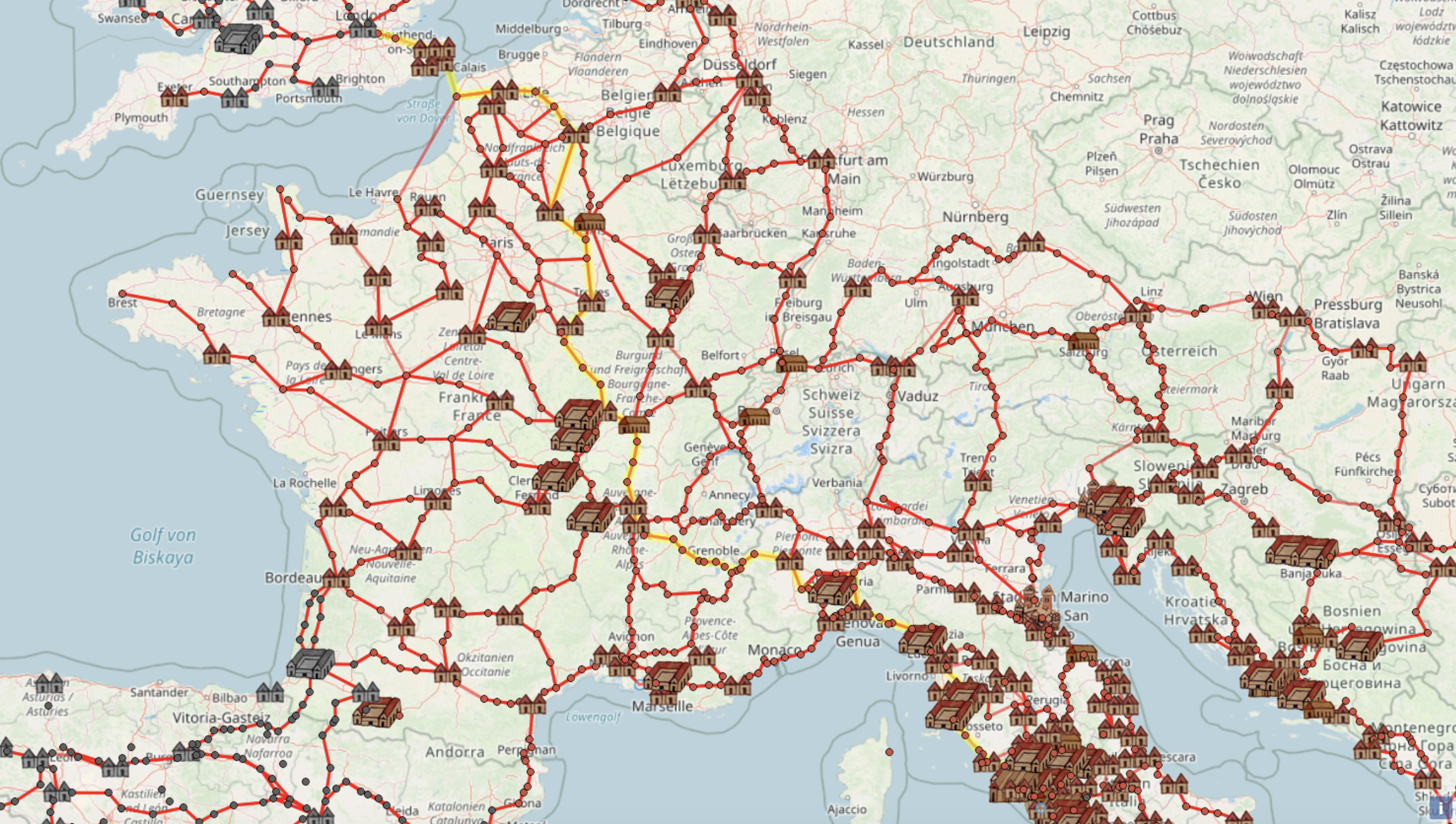

At the moment, I happen to be planning some time in France, with a side trip to Belgium included. Modern intra-European train travel makes arranging the latter quite convenient: Thalys, the high-speed rail service connecting those two countries, can get you from Paris to Brussels in about an hour and half. This stands in contrast to the time of the Roman Empire, which despite its political power lacked high-speed rail, and indeed lacked rail of any kind. But it did have an expansive network of roads, some of which you can still walk today, imagining what it would have been like to travel Europe two millennia ago. And now, using the website OmnesViae, you can get historically accurate directions as well.

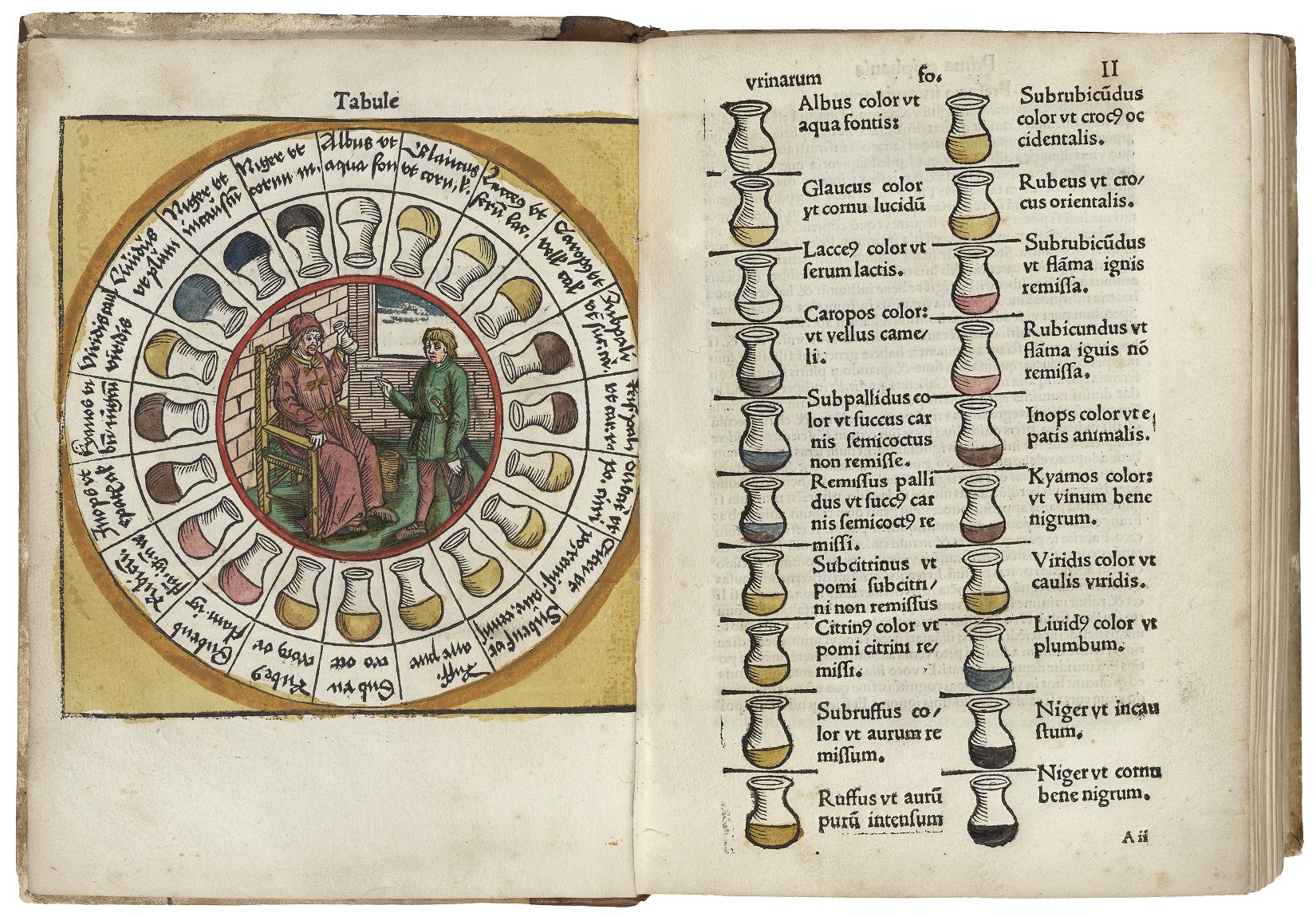

Big Think’s Frank Jacobs describes OmnesViae as “the online route planner the Romans never knew they needed.” It “leans heavily on the Tabula Peutingeriana” — also known as the Peutinger Map, and previously featured here on Open Culture — “the closest thing we have to a genuine itinerarium (‘road map’) of the Roman Empire.”

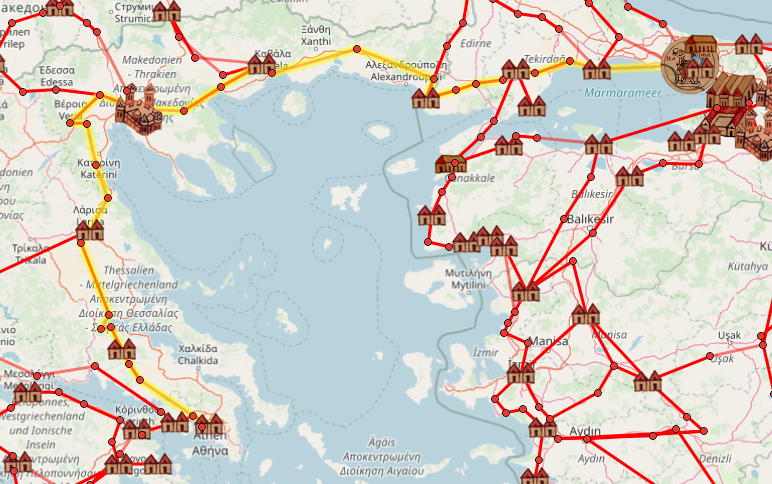

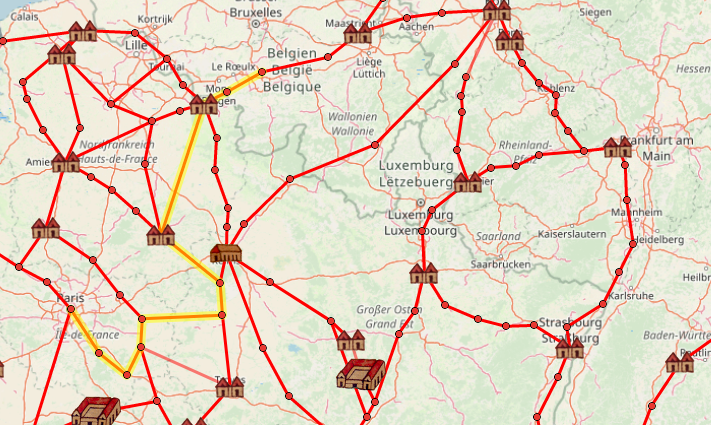

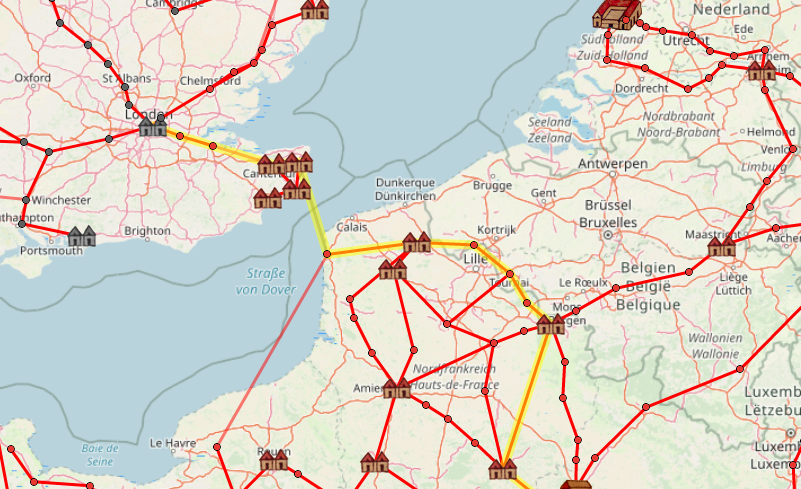

Though not quite geographically accurate, it does offer a detailed view of which cities in the empire were connected and how. “Geolocating thousands of points from Peutinger, OmnesViae reformats the roads and destinations on the scroll onto a more familiarly landscaped map. The shortest route between two (ancient) points is calculated using the distances traveled over Roman rather than modern roads, also taking into account the rivers and mountains the network must cross.”

You can use OmnesViae just like any other way-finding application, except you enter your origin and destination into fields labeled “ab” and “ad” rather than “from” and “to.” And though “for some cities current day names are understood,” as the instructions note, it works better — and feels so much more authentic — if you type in cities like “Roma” and “Londinio.” The resulting journey between those two great capitals looks arduous indeed, passing at least three mountainous areas, thirteen rivers, and countless smaller settlements. And according to OmnesViae, no roads led to Brussels: the closest an ancient traveler could get to the location of the modern-day seat of the European Union was the Walloon village of Liberchies — which, as the birthplace of Django Reinhardt, remains an important stop for the jazz-loving traveler of Europe today.

via Big Think

Related content:

The Roads of Ancient Rome Visualized in the Style of Modern Subway Maps

How the Ancient Romans Built Their Roads, the Lifelines of Their Vast Empire

The Roman Roads and Bridges You Can Still Travel Today

How to Make Roman Concrete, One of Human Civilization’s Longest-Lasting Building Materials

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.