As any new parent soon finds out, there exists a robust market for products, services, and media that promise to boost a child’s intelligence. Some of these offerings come as close as legally possible to holding out the promise of putting any tot on the path to genius, brazenly begging the question of whether it’s possible to raise a genius in the first place. Still, the efforts parents have deliberately made in that direction have occasionally produced notable results, from epochal figures like Mozart or John Stuart Mill to the promising-mathematician-turned-streetcar-transfer-obsessed-recluse William Sidis. More recently came the Polgár sisters, who were successfully raised to become some of the greatest female chess players in history.

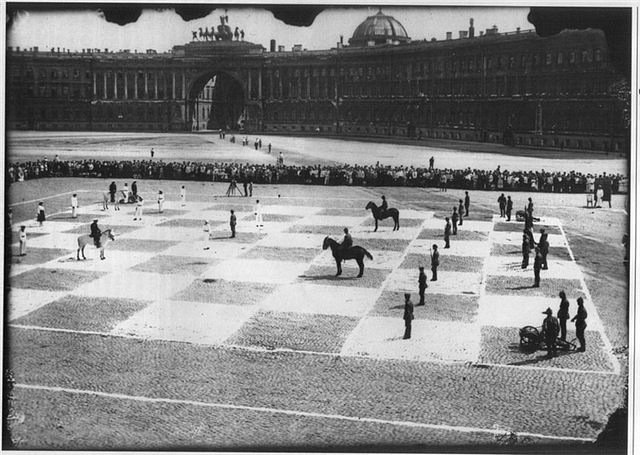

Having studied the nature of intelligence at university, their father László got it in his head that, since most geniuses started learning their subjects intensively and early, parents could cultivate genius-level performance in their children by directing that learning process themselves. He sought out a wife both intellectually promising and willing to devote herself to testing this hypothesis. Together they went on to father three daughters, putting them through a rigorous, custom-made education oriented toward chess mastery. Chess became the project’s central subject in large part because of its sheer objectivity, all the better for László Polgár to measure the results of this domestic experiment.

Nor could it have hurt, given the importance of retaining the interest of children, that chess was a game — and one with evocative toy-like pieces — that offers immediate feedback and feelings of accomplishment. For his daughters, Polgár has emphasized, learning involved none of the drudgery and busywork of school. “A child does not like only play: for them it is also enjoyable to acquire information and solve problems,” he writes in his book Raise a Genius! “A child’s work can also be enjoyable; so can learning, if it is sufficiently motivating, and if it means a constant supply of problems to solve that are appropriate for the level of the child’s needs. A child does not need play separate from work, but meaningful action.”

The proof of Polgár’s theories is in the pudding — or at any rate, in the ratings. All three of his daughters became elite chess players. Sofia, the middle one, became the sixth-strongest female player in the world; Susan, the eldest, the top-ranked female player in the world; Judit, the youngest, the strongest female chess player of all time. This despite the fact that their father was an unexceptional chess player, and their mother not a chess player at all. Some eagerly take the story of the Polgár sisters as a vindication of nurture over nature; others, scientific researchers included, argue that it only shows that practice is a necessary condition for this kind of genius, not a sufficient one. For my part, having kept an eye on a pair of infant twins while writing this, I’d be happy if my own kids could just master holding on to their bottles.

Related content:

Learn How to Play Chess Online: Free Chess Lessons for Beginners, Intermediate Players & Beyond

Meet Alma Deutscher, the Classical Music Prodigy: Watch Her Performances from Age 6 to 14

Hear the Pieces Mozart Composed When He Was Only 5 Years Old

Read an 18th-Century Eyewitness Account of 8‑Year-Old Mozart’s Extraordinary Musical Skills

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. He’s the author of the newsletter Books on Cities as well as the books 한국 요약 금지 (No Summarizing Korea) and Korean Newtro. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.