Certain directors like to implicate their audience in their onscreen crimes, drawing on decades of expectations created by popular cinematic tropes and playing with the viewer’s innate desires. Filmmaker Michael Haneke takes a Hitchcockian approach in this regard, in nightmarish visions like Benny’s Video, The Piano Player, and Caché. “Haneke uses voyeurism to dismantle the space between the film and audience,” writes Popmatters,” and in doing so, he takes advantage of what might be thought of as Hitchcock’s voyeur apparatus and forces the audience to question its place within the narrative.”

Hitchcock’s “voyeur apparatus” has inspired many another idiosyncratic filmmaker — most notably, perhaps, David Lynch. Like Jimmy Stewart’s Jeff Jeffries in Hitchcock’s Rear Window, Kyle MacLachlan’s Jeffrey in Lynch’s Blue Velvet becomes corrupted by illicit vision.

These are classic iterations of the Peeping Tom, the casual voyeur sexually awakened by covert observations of others. The road from Hitchcock to the psychosexual alienation of later arthouse cinema may be a short one, but where did Hitchcock’s framing of the voyeuristic gaze come from?

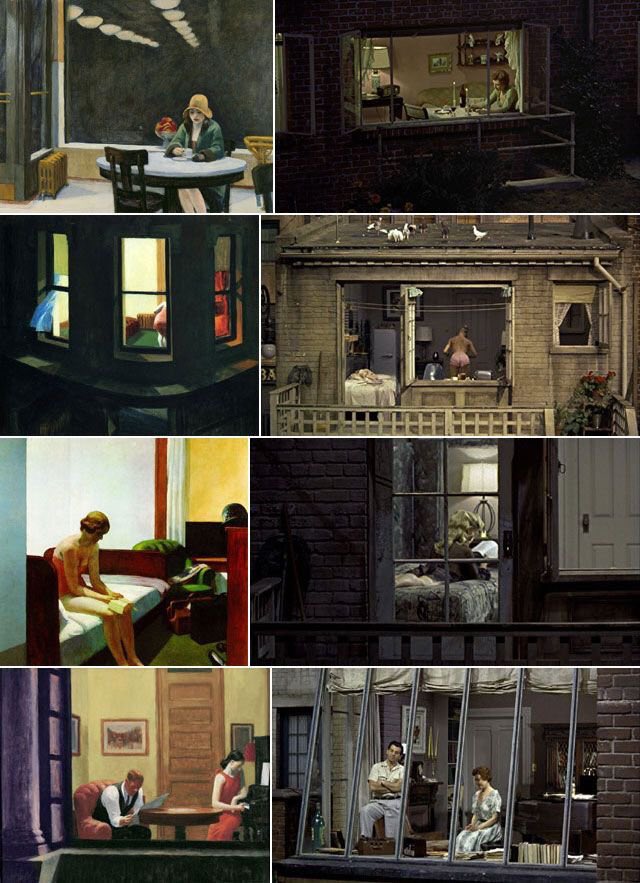

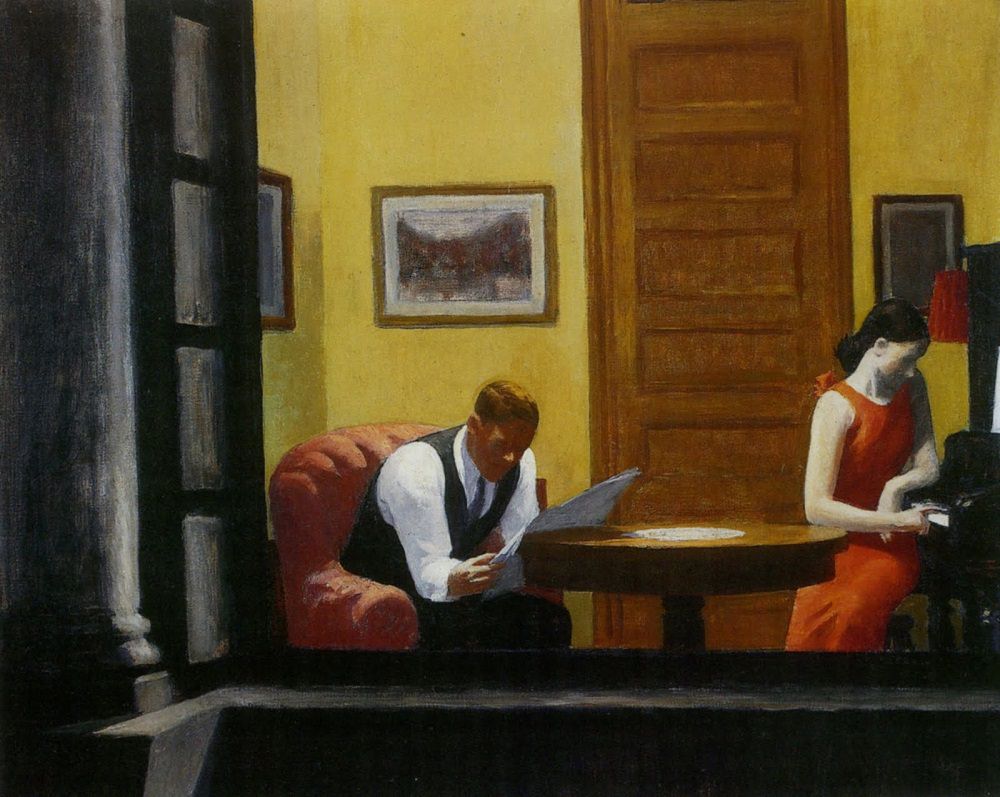

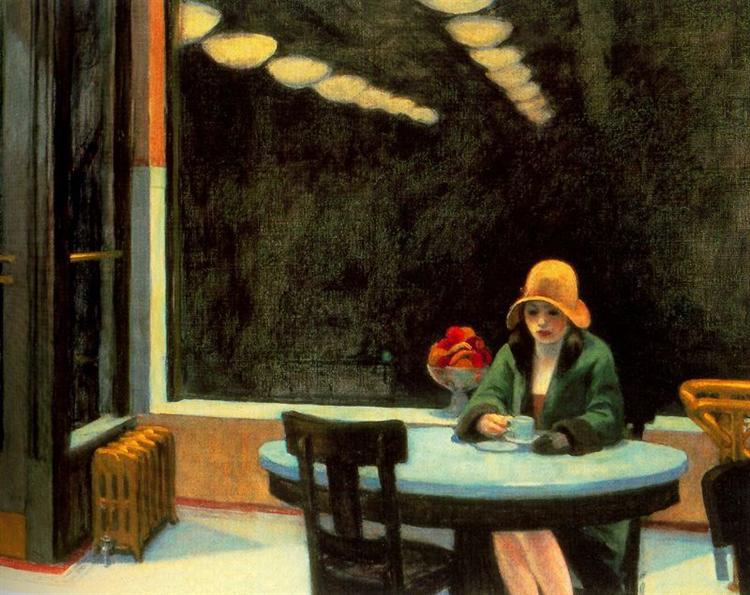

One answer, says writer Diane Doniol-Valcroze — daughter of Cahiers Du Cinéma co-founder Jacques Doniol-Valcroze — is found in a comparison of Hitchcock’s visual sense with that of Edward Hopper, the inventer of midcentury modern loneliness and also himself kind of a classic Peeping Tom. In a series of juxtapositions on Twitter, Doniol-Valcroze shows how Hitchcock adopted the framing of paintings like Hopper’s Automat (1927), Night Windows (1928), Hotel Room (1931), Room in New York (1932) for shots of Rear Window’s “Miss Torso” and “Miss Lonelyhearts.” She is not the only critic to make the comparison.

“For Hitchcock in particular,” writes Finn Blythe at Hero, “Hopper’s gaze was like a petri dish from which an infinite number of possible narratives could grow. Evidence of Hopper’s influence can be found throughout Hitchcock’s oeuvre, but especially his 1954 classic Rear Window. Just as the power of Hopper’s paintings lies in what he chooses to exclude, so the tension and spectacle in Hitchcock’s Rear Window relies on what is obscured or unseen.” Hopper’s figures are not only lonely and alienated, they are vulnerable, and especially so in private, unguarded moments in their own homes.

Hitchcock takes Hopper’s gaze, so often framed by windows, and makes it about cinema itself. “As viewers,” writes Blythe, “we become complicit in the same morbid human fantasies,” as Stewart’s creepy Jeff, “rubber-necking the same lurid acts from the safe vantage point of our chairs.” As the cinematic image of the voyeur has shown us, however — in Hitchcock, Haneke, Lynch, and its many iterations of what Laura Mulvey called the “male gaze” — the act of watching from a distance can become a kind of violence all its own; in Hitchcockian cinema, the menace that often seems to lurk just out of frame in Hopper’s paintings can burst into the picture at any moment.

Related Content:

Alfred Hitchcock Reveals The Secret Sauce for Creating Suspense

Edward Hopper’s Iconic Painting Nighthawks Explained in a 7‑Minute Video Introduction

How Edward Hopper “Storyboarded” His Iconic Painting Nighthawks

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

I have been deeply moved by Hitchcock since childhood. I also very much admire David Lynch, and of course Hopper. However, some people overthink these things. Fascination or keen observation isn’t necessarily the “male gaze”, a hostile term which strikes me as offensive and sexist. And, absent creepy and dishonest circumstances, looking at someone through an uncovered window, visible to anyone with a view of such a window, for example, can only be called a “kind of violence” by someone who doesn’t know what violence is. Remarkable—an article that on one hand recognizes the talent and brilliance of several artists and filmmakers, and on the other suggests perversion.

The text of the article is great, and I found your text fascinating. However, I couldn’t help notice that the the visuals align rather closely with research I performed first with regard to the affinities between Hitchcock and Hopper in REAR WINDOW. http://www.alfredhitchcockgeek.com/2009/11/alfred-hitchcock-edward-hopper-and.html