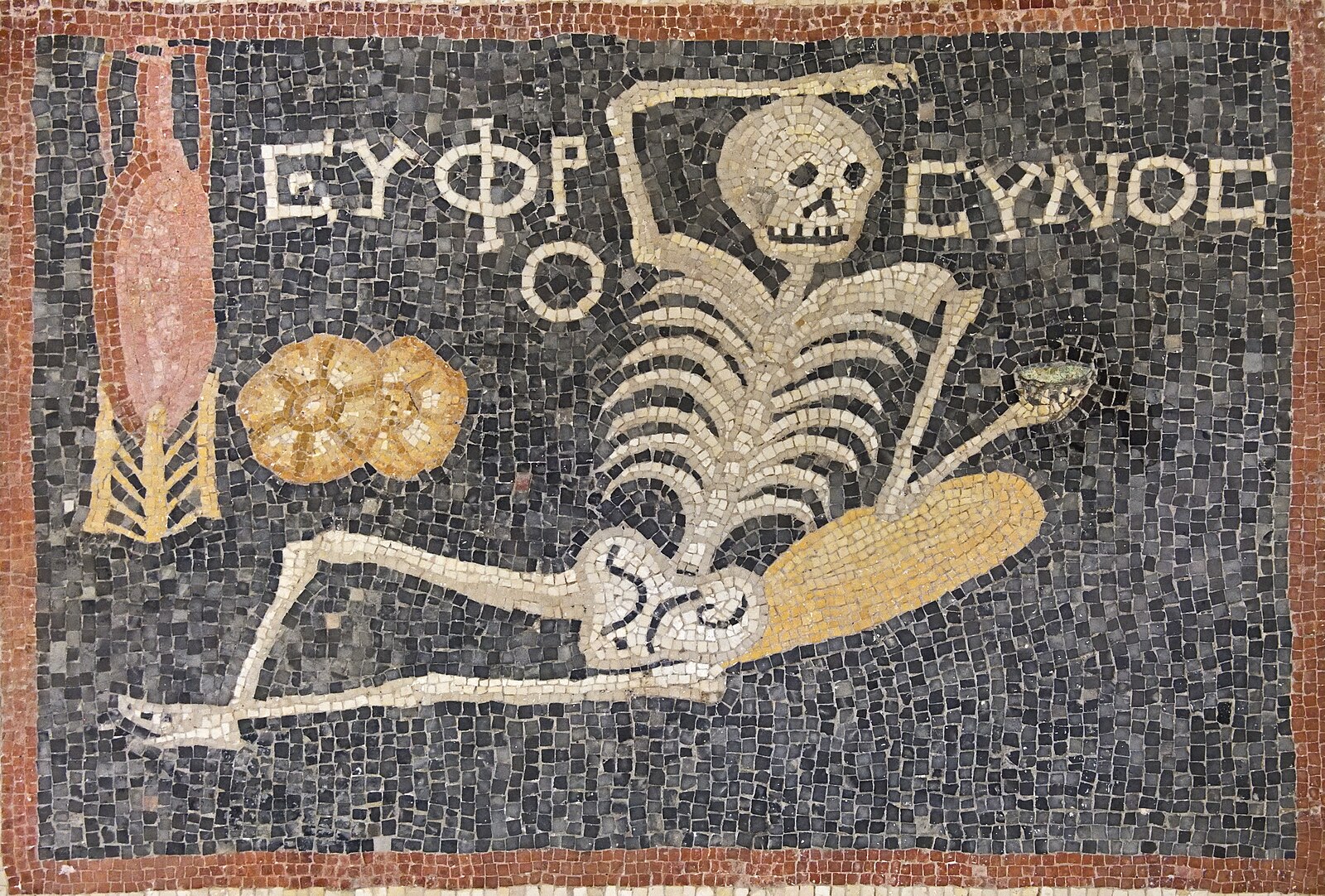

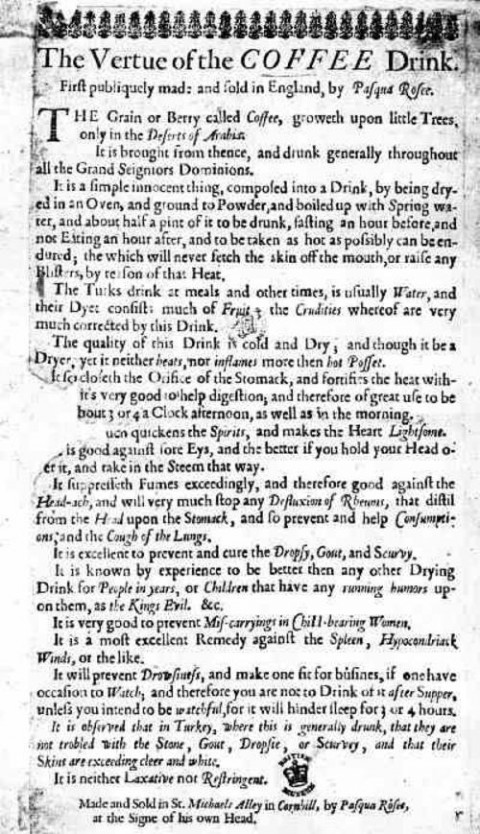

“Early cookbooks were fit for kings,” writes Henry Notaker at The Atlantic. “The oldest published recipe collections” in the 15th and 16th centuries in Western Europe “emanated from the palaces of monarchs, princes, and grand señores.” Cookbooks were more than recipe collections—they were guides to court etiquette and sumptuous records of luxurious living. In ancient Rome, cookbooks functioned similarly, as the extravagant fourth century Cooking and Dining in Imperial Rome demonstrates.

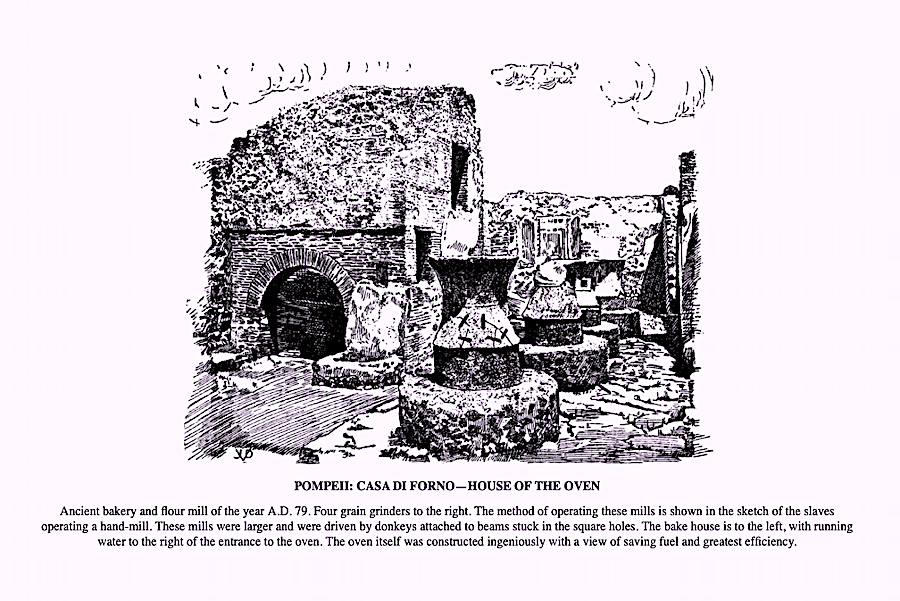

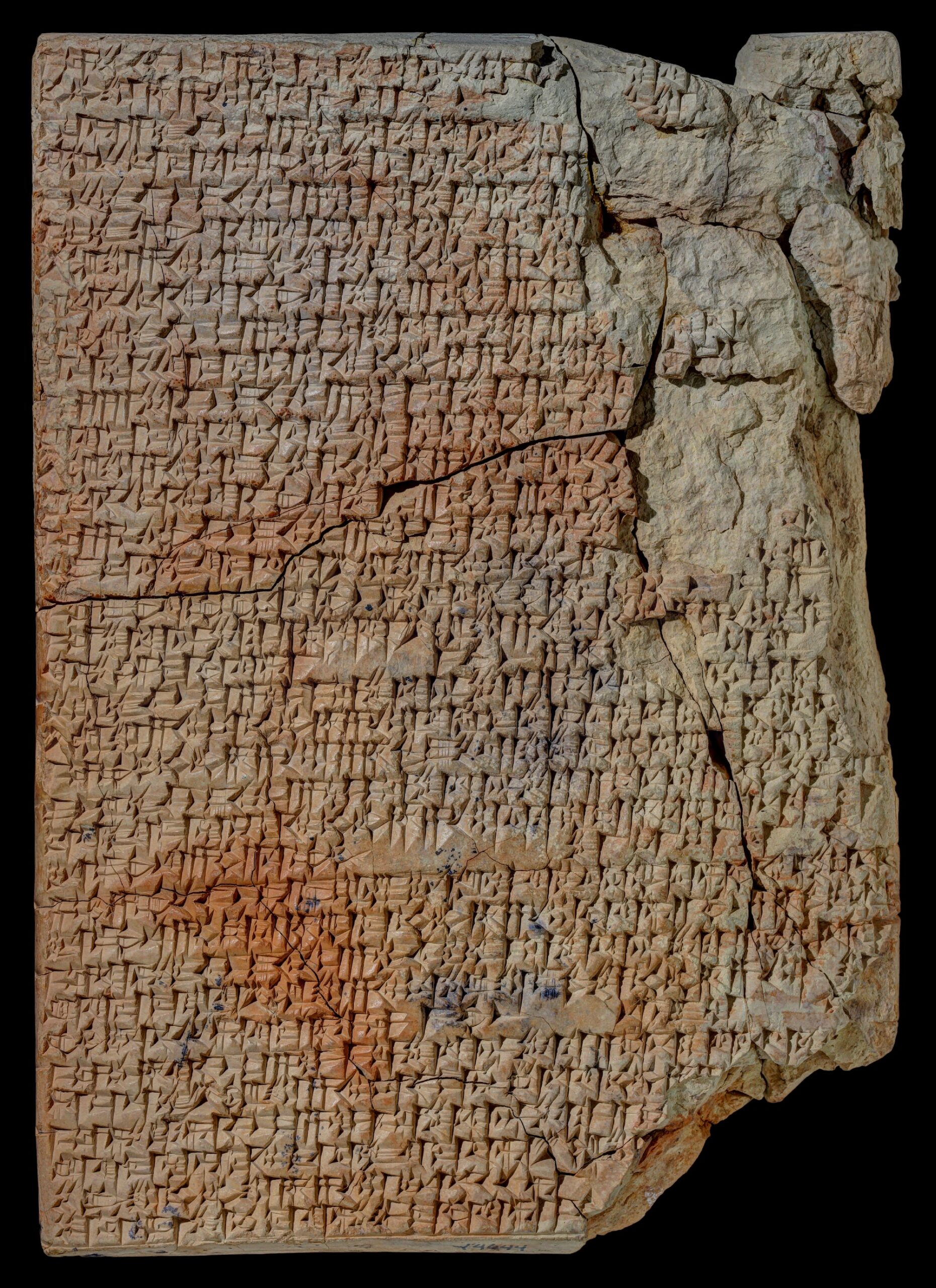

Written by Apicius, “Europe’s oldest [cookbook] and Rome’s only one in existence today”—as its first English translator described it—offers “a better way of knowing old Rome and antique private life.” It also offers keen insight into the development of heavily flavored dishes before the age of refrigeration. Apicius recommends that “cooks who needed to prepare birds with a ‘goatish smell’ should bathe them in a mixture of pepper, lovage, thyme, dry mint, sage, dates, honey, vinegar, broth, oil and mustard,” Melanie Radzicki McManus notes at How Stuff Works.

Early cookbooks communicated in “a folksy, imprecise manner until the Industrial Revolution of the 1800s,” when standard (or metric) measurement became de rigueur. The first cookbook by an American, Amelia Simmons’ 1796 American Cookery, placed British fine dining and lavish “Queen’s Cake” next to “johnny cake, federal pan cake, buckwheat cake, and Indian slapjack,” Keith Stavely and Kathleen Fitzgerald write at Smithsonian, all recipes symbolizing “the plain, but well-run and bountiful American home.” With this book, “a dialogue on how to balance the sumptuous with the simple in American life had begun.”

Cookbooks are windows into history—markers of class and caste, documents of daily life, and snapshots of regional and cultural identity at particular moments in time. In 1950, the first cookbook written by a fictional lifestyle celebrity, Betty Crocker, debuted. It became “a national best-seller,” McManus writes. “It even sold more copies that year than the Bible.” The image of the perfect Stepford housewife may have been bigger than Jesus in the 50s, but Crocker’s career was decades in the making. She debuted in 1921, the year of publication for another, more humble recipe book: the Pilgrim Evangelical Lutheran Church Ladies’ Aid Society of Chicago’s Pilgrim Cook Book.

As Ayun Halliday noted in an earlier post, this charming collection features recipes for “Blitz Torte, Cough Syrup, and Sauerkraut Candy,” and it’s only one of thousands of such examples at the Internet Archive’s Cookbook and Home Economics Collection, drawn from digitized special collections at UCLA, Berkeley, and the Prelinger Library. When we last checked in, the collection featured 3,000 cookbooks. It has grown since 2016 to a library of 12,700 vintage examples of homespun Americana, fine dining, and mass marketing.

Laugh at gag-inducing recipes of old; cringe at the pious advice given to women ostensibly anxious to please their husbands; and marvel at how various international and regional cuisines have been represented to unsuspecting American home cooks. (It’s hard to say whether the cover or the contents of a Chinese Cook Book in Plain English from 1917 seem more offensive.) Cookbooks of recipes from the American South are popular, as are covers featuring stereotypical “mammy” characters. A more respectful international example, 1952’s Luchow’s German Cookbook gives us “the story and the favorite dishes of America’s most famous German restaurant.”

There are guides to mushrooms and “commoner fungi, with special emphasis on the edible varieties”; collections of “things mother used to make” and, most practically, a cookbook for leftovers. And there is every other sort of cookbook and home ec manual you could imagine. The archive is stuffed with helpful hints, rare ingredients, unexpected regional cookeries, and millions of minute details about the habits of these books’ first hungry readers.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2020.

Related Content:

A Database of 5,000 Historical Cookbooks–Covering 1,000 Years of Food History–Is Now Online

Discover the World’s Oldest Surviving Cookbook, De Re Coquinaria, from Ancient Rome

The World’s Oldest Cookbook: Discover 4,000-Year-Old Recipes from Ancient Babylon

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC.