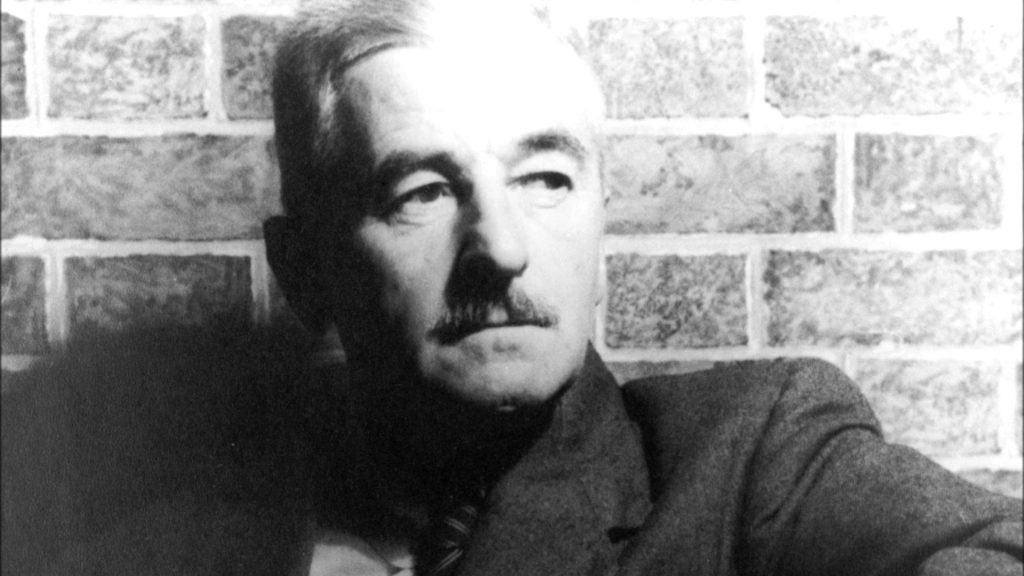

“The young writer would be a fool to follow a theory,” said the Nobel Prize-winning author William Faulkner in his 1958 Paris Review interview. “Teach yourself by your own mistakes; people learn only by error. The good artist believes that nobody is good enough to give him advice.”

All the same, Faulkner offered plenty of advice to young writers in 1957 and 1958, when he was a writer-in-residence at the University of Virginia. His various lectures and public talks during that time–some 28 hours of discussion–were tape recorded and can now be heard at the university’s Faulkner audio archive. We combed through the transcripts and selected seven interesting quotations from Faulkner on the craft of writing fiction. In most cases they were points Faulkner returned to again and again. Faulkner had a way of stammering when he composed his words out loud, so we have edited out the repetitions and false starts. We have provided links to each of the Virginia audio recordings, which are accompanied by word-for-word transcripts of each conversation.

1: Take what you need from other writers.

Faulkner had no qualms about borrowing from other writers when he saw a device or technique that was useful. In a February 25, 1957 writing class he says:

I think the writer, as I’ve said before, is completely amoral. He takes whatever he needs, wherever he needs, and he does that openly and honestly because he himself hopes that what he does will be good enough so that after him people will take from him, and they are welcome to take from him, as he feels that he would be welcome by the best of his predecessors to take what they had done.

2: Don’t worry about style.

A genuine writer–one “driven by demons,” to use Faulkner’s phrase–is too busy writing to worry about style, he said. In an April 24, 1958 undergraduate writing class, Faulkner says:

I think the story compels its own style to a great extent, that the writer don’t need to bother too much about style. If he’s bothering about style, then he’s going to write precious emptiness–not necessarily nonsense…it’ll be quite beautiful and quite pleasing to the ear, but there won’t be much content in it.

3: Write from experience–but keep a very broad definition of “experience.”

Faulkner agreed with the old adage about writing from your own experience, but only because he thought it was impossible to do otherwise. He had a remarkably inclusive concept of “experience.” In a February 21, 1958 graduate class in American fiction, Faulkner says:

To me, experience is anything you have perceived. It can come from books, a book that–a story that–is true enough and alive enough to move you. That, in my opinion, is one of your experiences. You need not do the actions that the people in that book do, but if they strike you as being true, that they are things that people would do, that you can understand the feeling behind them that made them do that, then that’s an experience to me. And so, in my definition of experience, it’s impossible to write anything that is not an experience, because everything you have read, have heard, have sensed, have imagined is part of experience.

4: Know your characters well and the story will write itself.

When you have a clear conception of a character, said Faulkner, events in a story should flow naturally according to the character’s inner necessity. “With me,” he said, “the character does the work.” In the same February 21, 1958 American fiction class as above, a student asked Faulkner whether it was more difficult to get a character in his mind, or to get the character down on paper once he had him in his mind. Faulkner replies:

I would say to get the character in your mind. Once he is in your mind, and he is right, and he’s true, then he does the work himself. All you need to do then is to trot along behind him and put down what he does and what he says. It’s the ingestion and then the gestation. You’ve got to know the character. You’ve got to believe in him. You’ve got to feel that he is alive, and then, of course, you will have to do a certain amount of picking and choosing among the possibilities of his action, so that his actions fit the character which you believe in. After that, the business of putting him down on paper is mechanical.

5: Use dialect sparingly.

In a pair of local radio programs included in the University of Virginia audio archive, Faulkner has some interesting things to say about the nuances of the various dialects spoken by the various ethnic and social groups in Mississippi. But in the May 6, 1958 broadcast of “What’s the Good Word?” Faulkner cautions that it’s important for a writer not to get carried away:

I think it best to use as little dialect as possible because it confuses people who are not familiar with it. That nobody should let the character speak completely in his own vernacular. It’s best indicated by a few simple, sparse but recognizable touches.

6: Don’t exhaust your imagination.

“Never write yourself to the end of a chapter or the end of a thought,” said Faulkner. The advice, given more than once during his Virginia talks, is virtually identical to something Ernest Hemingway often said. (See tip number two in “Seven Tips From Ernest Hemingway on How to Write Fiction.”) In the February 25, 1957 writing class, Faulkner says:

The only rule I have is to quit while it’s still hot. Never write yourself out. Always quit when it’s going good. Then it’s easier to take it up again. If you exhaust yourself, then you’ll get into a dead spell and you’ll have trouble with it.

7: Don’t make excuses.

In the same February 25, 1957 writing class, Faulkner has some blunt words for the frustrated writer who blames his circumstances:

I have no patience, I don’t hold with the mute inglorious Miltons. I think if he’s demon-driven with something to be said, then he’s going to write it. He can blame the fact that he’s not turning out work on lots of things. I’ve heard people say, “Well, if I were not married and had children, I would be a writer.” I’ve heard people say, “If I could just stop doing this, I would be a writer.” I don’t believe that. I think if you’re going to write you’re going to write, and nothing will stop you.

Related content:

Seven Tips From Ernest Hemingway on How to Write Fiction

Seven Tips From F. Scott Fizgerald on How to Write Fiction

Regarding Faulkner’s #1 tip:

1: Take what you need from other writers.

Did he take the title Light in August from

Chapter 1 of Heart of Darkness…

“the august light of abiding memories.” ?

Reassuring and enlightening. Thank you

Presumably Conrad intended to convey the light as impressive. It doesn’t appear to relate to the month of August, as Faulkner’s title suggests.

It doesn’t really matter what Conrad intended to convey by his use of “august.” What matters is how the reader sees, perceives the word. The reader brings his(her)experience into the equation. Context will have its influence, but the reader must supply his (her) interpretation. How is the reader, for example, to interpret the word “wants?” Does the word mean desires or does it mean lacks? Context should help the reader determine which meaning the writer intended. But there are no guarantees. The only solution is to read and read and read.