All things we humans use, from our advanced mobile phones to our very arms and legs, reached their current states through a process of evolution. The same, naturally, goes for our punctuation marks. These tools we use to separate, connect, or draw attention to our words and sentences had different forms and uses in bygone times, and Scotland-based medical visualization software programmer Keith Houston has taken it upon himself to trace paths through all of them. In the introduction to his history-of-punctuation blog Shady Characters, he recounts his unlikely source of inspiration in Eric Gill’s Essay on Typography: “my interest was piqued by the unusual character resembling a reversed capital ‘P’ — ‘¶’ — which peppered the text at apparently random intervals.” This little-discussed mark, called a pilcrow, led Houston to ask the sort of questions that drive his project: “How did the pilcrow’s curious reverse‑P form come about? What were the roots of its pithy, half-familiar name? What caused it to fall out of use, and having done just that, why did Eric Gill see fit to place them seemingly at random in his only published work on typography? What, in other words, was the pilcrow all about?”

All things we humans use, from our advanced mobile phones to our very arms and legs, reached their current states through a process of evolution. The same, naturally, goes for our punctuation marks. These tools we use to separate, connect, or draw attention to our words and sentences had different forms and uses in bygone times, and Scotland-based medical visualization software programmer Keith Houston has taken it upon himself to trace paths through all of them. In the introduction to his history-of-punctuation blog Shady Characters, he recounts his unlikely source of inspiration in Eric Gill’s Essay on Typography: “my interest was piqued by the unusual character resembling a reversed capital ‘P’ — ‘¶’ — which peppered the text at apparently random intervals.” This little-discussed mark, called a pilcrow, led Houston to ask the sort of questions that drive his project: “How did the pilcrow’s curious reverse‑P form come about? What were the roots of its pithy, half-familiar name? What caused it to fall out of use, and having done just that, why did Eric Gill see fit to place them seemingly at random in his only published work on typography? What, in other words, was the pilcrow all about?”

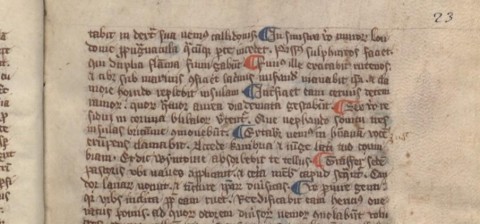

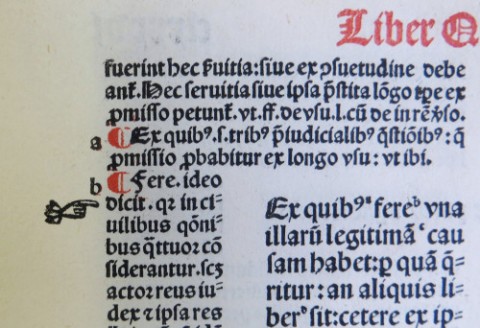

In a recent New Yorker post, Houston works toward the answers by looking back to the pilcrow’s precursors. “Before there was any other punctuation there was the paragraphos—from the Greek para-, ‘beside,’ and graphein, ‘write’,” he explains. “A simple horizontal stroke placed in the left margin beside a line of text, the paragraphos was used in ancient Greece to call attention to conceptual changes in an otherwise unbroken block of text: a new topic, perhaps, or a new stanza in a poem.” This, over the centuries, became the pilcrow, just as “the Latin abbreviation ‘lb,’ for the Roman term libra pondo, or ‘pound weight,’ ” turned into the #, or the hash mark, or — better yet —the octothorpe. As for ☞, that little hand, Houston tells us its proper name: manicule, “taken,” naturally enough, “from the Latin maniculum, or ‘little hand.’ ” With earliest use found in the Domesday Book of 1086, the manicule, “a mark that readers drew to call out points of interest,” enjoyed great prevalence until the fifteenth-century printing press came along, when, “with printed versions of the symbol—and of other reference marks such as * and †—now available to writers, ‘authorized’ notes began to spring up in the margins, encroaching upon the space once available to the reader.”

Houston’s work on the history of punctuation has now taken the form of a book: Shady Characters: The Secret Life of Punctuation, Symbols & Other Typographical Marks. But you can still read a wealth of his scholarship on the pilcrow, octothorpe, the manicule, and other symbols both current and forgotten, on his blog, all clearly organized on its table of contents. Who could turn down that good day’s reading‽

via The New Yorker

Related Content:

Cormac McCarthy’s Three Punctuation Rules, and How They All Go Back to James Joyce

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.

Terrific! u2013 how marvellous it must be to be a researcher and come up with this kind of fascinating material …nnI hope this work will stave off the death (as the next step from today’s dearth) of punctuation.nnI wrote a book, a memoir, and my publisher and I argued very happily about the punctuation for months. :-)

It was certainly an enjoyable time. The next book promises to be just as interesting to write!