Isaiah Berlin casts a long shadow over modern political philosophy. Rising to prominence as a British public intellectual in the 1950s alongside thinkers like A.J. Ayer and Hugh Trevor-Roper, Berlin (writes Joshua Chemiss in The Oxonian Review of Books) was at one time a “cold warrior,” his opposition to Soviet Communism the “lynchpin” of his thought. But his longevity and intellectual vitality meant he was much more besides, and he has remained a popular reference, though, as Chemiss points out, Berlin’s reputation took a beating from critics on the left and right after his death in 1997. Born into a prominent Russian-Jewish family, Berlin grew up in middle class stability until the Russian Revolution dismantled the Czarist Russia of his youth and his family relocated to Britain in 1921.

Berlin’s childhood experience of the Bolsheviks was never far from his mind and precipitated his aversion to violence and coercion, he confesses above in a 1992 interview with his biographer Michael Ignatieff (who spent ten years in conversation with Berlin). Originally broadcast on BBC 2, Ignatieff’s interview serves as an introduction to both the man himself and to his past—in lengthy segments that detail Berlin’s history through photographs and narration. Referring to Berlin’s hugely influential categorization of intellectual history, The Hedgehog and the Fox, Ignatieff tells us: “He once wrote, ‘A fox knows many things, but a hedgehog knows one, big thing.’ He was a hedgehog, all his work was a defense of liberty.… All of his writing can be read as a defense of the individual against the violence of the crowd and the dogma of the party line.”

Berlin was enormously prolific, in print as well as in recorded media, and we have access to several of his lectures online. One radio lecture series, Freedom and its Betrayal, examined six thinkers Berlin identified as “anti-liberal.” Perhaps foremost among these was Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In his lecture on Rousseau above (continued here in Parts 2, 3, 4, 5 & 6), Berlin elaborates on his important distinction between types of liberty, a theme he returned to again and again, most famously in a lecture, eventually published as a 57-page pamphlet, called “Two Concepts of Liberty.” Berlin adapted much of the ideas in these lectures from his Political Ideas in the Romantic Age—written between 1950 and 1952 and published posthumously—a text that Berlin called his “torso.”

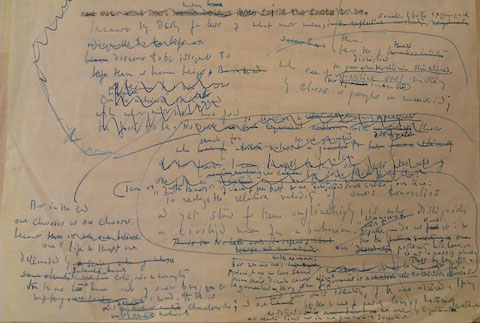

Oxford University hosts an extensive “Isaiah Berlin Virtual Library” that details the composition of “Two Concepts of Liberty,” from its earliest draft stages (above) to its publication history. You can read the full text of the published lecture here and listen to Berlin’s recorded dictation of an early draft below.

In the published version of “Two Concepts of Liberty,” Berlin succinctly sums up his major premise: “To coerce a man is to deprive him of freedom.” Then he goes on:

freedom from what? Almost every moralist in human history has praised freedom. Like happiness and goodness, like nature and reality, the meaning of this term is so porous that there little interpretation that it seems able to resist….[There are] more than two hundred senses.… of this protean word….

Berlin reduces the more than two hundred to two: negative liberty—dealing with the areas of life in which one is free from any interference; and positive liberty—his term for that which interferes in people’s lives for their supposed benefit and protection. Berlin’s conceptions of these two types is anchored in specific geopolitical arrangements and philosophical traditions, as Dwight MacDonald explained in a 1959 review of the published text. He saw Communism as an abuse of positive liberty and wished to enhance so-called negative liberty as much as possible. As such, Berlin is often cited approvingly by politicians and philosophers with more classical, limited understandings of state power, although these may include libertarians as well as liberals, finding common ground in values of ethical pluralism and robust civil liberties, both of which Berlin defended strenuously.

Berlin draws his account of negative liberty from the work of classical liberal political philosophers like John Locke, Adam Smith, and John Stuart Mill. Most of his critique of positive liberty focused on Romanticism and German Idealism, in which he saw the beginnings of totalitarianism (above, hear Berlin’s final 1965 lecture on the “Roots of Romanticism,” continued in Parts 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, & 7). Despite his preoccupation with kinds of freedom, his thought was extraordinarily idiosyncratic, wide-ranging, and diverse. Oxford hopes to soon add the text of much of Berlin’s published work to its Virtual Library. Now, in addition to “Two Concepts of Liberty,” it also houses online text of the essay collection Concepts and Categories. While we await the posting of more Berlin texts, we might attend again to Berlin’s conception of types of freedom, and hear them defined by the philosopher himself in a 1962 interview:

As in the case of words which everyone is in favour of, ‘freedom’ has a very great many senses – some of the world’s worst tyrannies have been undertaken in the name of freedom. Nevertheless, I should say that the word probably has two central senses, at any rate in the West. One is the familiar liberal sense in which freedom means that every man has a life to live and should be given the fullest opportunity of doing so, and that there are only two adequate reasons for controlling men. The first is that there are other goods besides freedom, such as, for example, security or peace or culture, or other things which human beings need, which must be given them, apart from the question of whether they want them or not. Secondly, if one man obtains too much, he will deprive other people of their freedom – freedom for the pike means death to the carp – and this is a perfectly adequate reason for curtailing freedom. Still, curtailing freedom isn’t the same as freedom.

The second sense of the word is not so much a matter of allowing people to do what they want as the idea that I want to be governed by myself and not pushed around by other people; and this idea leads one to the supposition that to be free means to be self-governing. To be self-governing means that the source of authority must lie in me – or in us, if we’re talking about a community. And if the source of freedom lies in me, then it’s comparatively unimportant how much control there is, provided the control is exercised by myself, or my representatives, or my nation, my people, my tribe, my Church, and so forth. Provided that I am governed by people who are sympathetic to me, or understand my interests, I don’t mind how much of my life is pried into, or whether there is a private province which is divided from the public province; and in some modern States – for example the Soviet Union and other States with totalitarian governments – this second view seems to be taken.

Between these two views, I see no possibility of reconciliation.

Related Content:

Leo Strauss: 15 Political Philosophy Courses Online

Introduction to Political Philosophy: A Free Yale Course

Alain de Botton Tweets Short Course in Political Philosophy

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Salve, volevo chiedere se esiste qualche traduzione in italiano delle interviste del Prof. Sir Isaiah Berlin.

Grazie, Nicola