The web site Overlook Hotel has posted pictures of Stanley Kubrick’s personal copy of Stephen King’s novel The Shining. The book is filled with highlighted passages and largely illegible notes in the margin—tantalizing clues to Kubrick’s intentions for the movie.

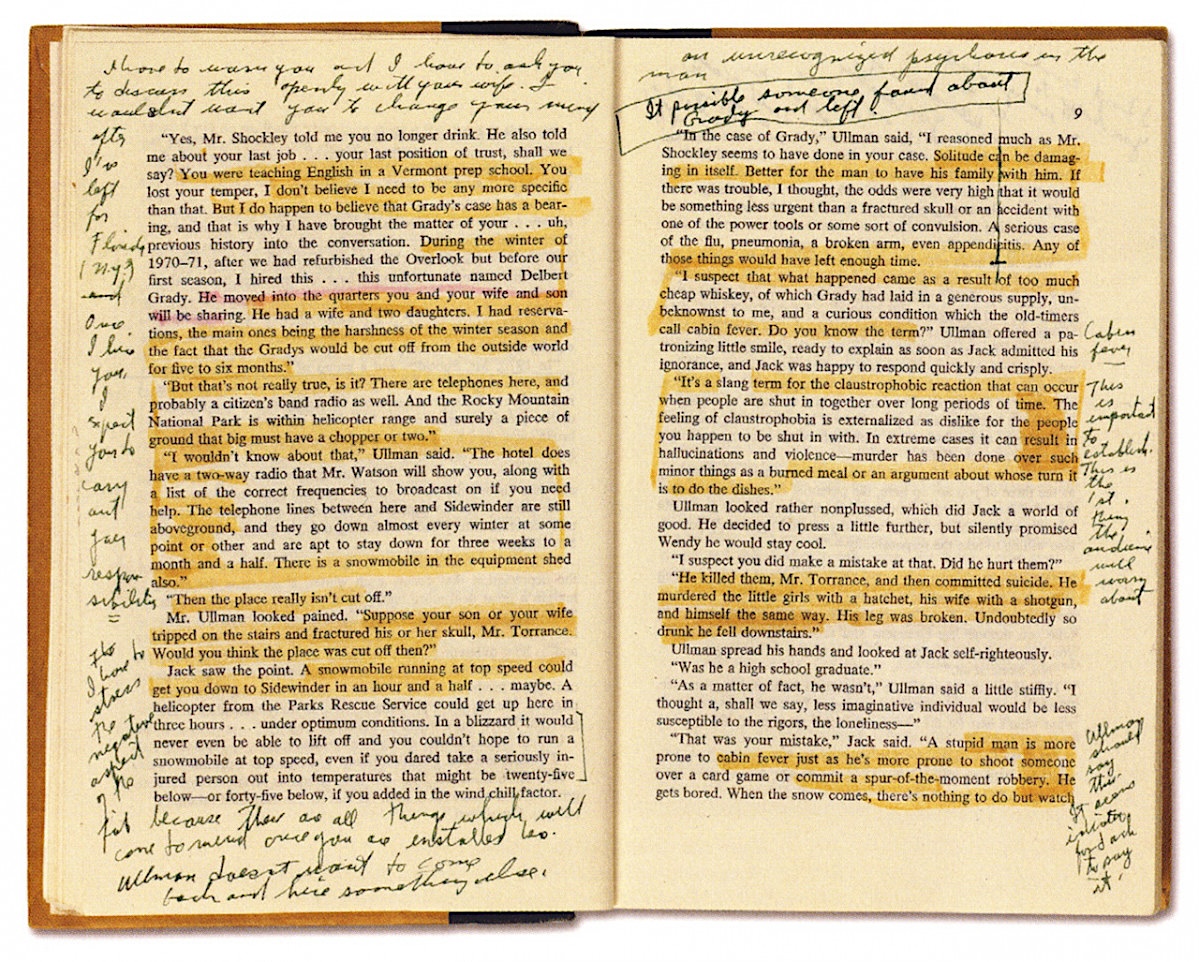

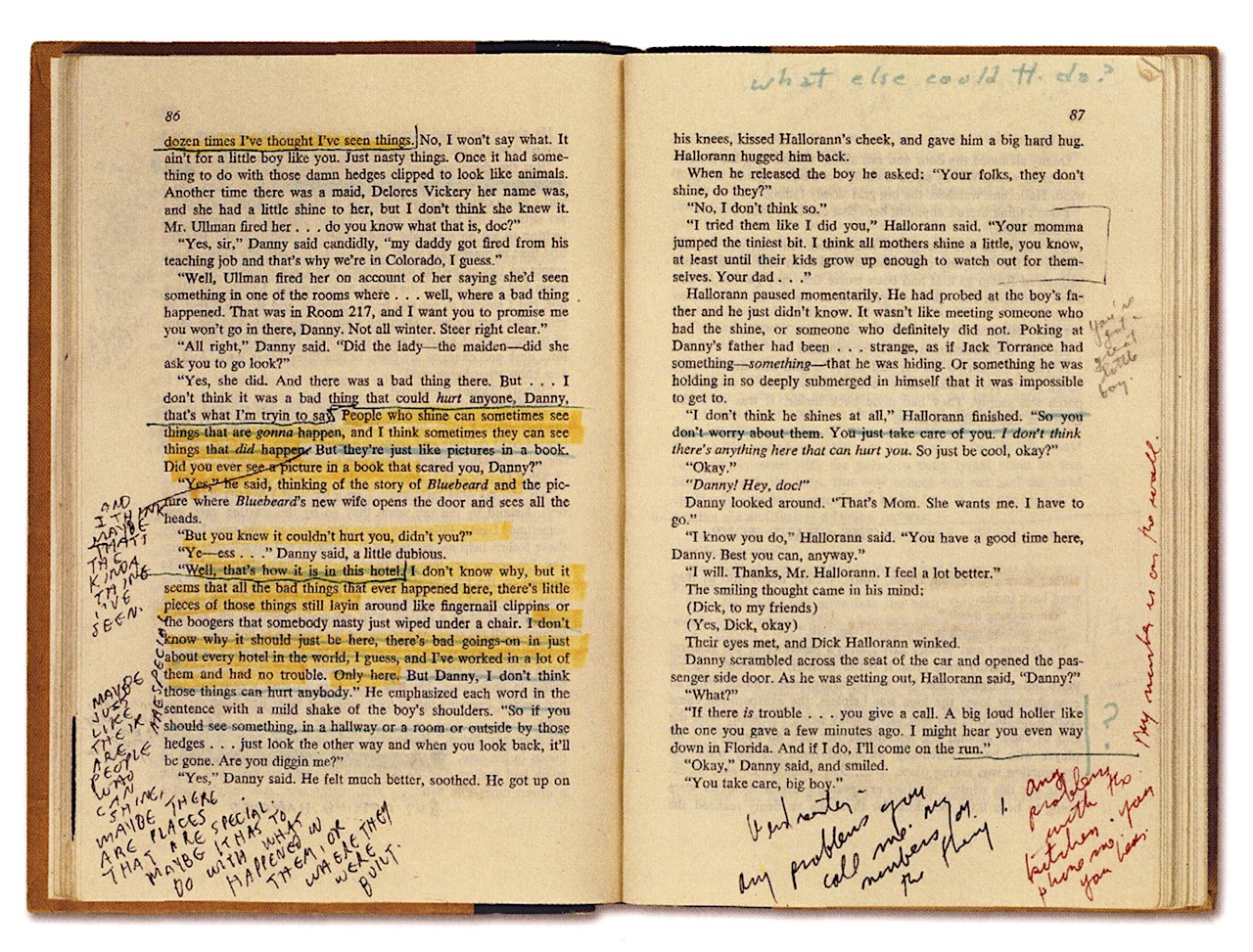

The site features a picture of the book’s careworn cover along with two spreads from the book’s interior —pages 8–9, where Jack Torrance is being interviewed by hotel manager Mr. Ullman, and pages 86–87 where hotel cook Dick Hallorann talks to Jack’s son Danny about the telepathic ability called “shining.”

Much of the marginalia is maddeningly hard to decipher. One of the notes I could make out reads:

Maybe just like their [sic] are people who can shine, maybe there are places that are special. Maybe it has to do with what happened in them or where they were built.

Kubrick is clearly working to translate King’s book into film. Other notes, however, seem wholly unrelated to the movie.

Any problems with the kitchen – you phone me.

When The Shining came out, it was greeted with tepid and nonplussed reviews. Since then, the film’s reputation has grown, and now it’s considered a horror masterpiece.

At first viewing, The Shining overwhelms the viewer with pungent images that etch themselves in the mind—those creepy twins, that rotting senior citizen in the bathtub, that deluge of blood from the elevator. Yet after the fifth or seventh viewing, the film reveals itself to be far weirder than your average horror flick. For instance, why is Jack Nicholson reading a Playgirl magazine while waiting in the lobby? What’s the deal with that guy in the bear suit at the end of the movie? Why is Danny wearing an Apollo 11 sweater?

While Stephen King has had dozens of his books adapted for the screen (many are flat-out terrible), of all the adaptations, this is one that King actively dislikes.

“I would do everything different,” complained King about the movie to American Film Magazine in 1986. “The real problem is that Kubrick set out to make a horror picture with no apparent understanding of the genre.” King later made his own screen version of his book. By all accounts, it’s nowhere as good as Kubrick’s.

Perhaps the reason King loathed Kubrick’s adaptation so much is that the famously secretive and controlling director packed the movie with so many odd signs, like Danny’s Apollo sweater, that seem to point to a meaning beyond a tale of an alcoholic writer who descends into madness and murder. The Shining is a semiotic puzzle about …what?

Critic after critic has attempted to crack the film’s hidden meaning. Journalist Bill Blakemore argued in his essay “The Family of Man” that The Shining is actually about the genocide of the Native Americans. Historian Geoffrey Cocks suggests that the movie is about the Holocaust. And conspiracy guru Jay Weidner has argued passionately that the movie is in fact Kubrick’s coded confession for his role in staging the Apollo 11 moon landing. (On a related note, see Dark Side of the Moon: A Mockumentary on Stanley Kubrick and the Moon Landing Hoax.)

Rodney Ascher’s 2012 documentary Room 237 juxtaposes all of these wildly divergent readings, brilliantly showing just how dense and multivalent The Shining is. You can see the trailer for the documentary above.

Note: Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2014.

Related Content:

How Stanley Kubrick Adapted Stephen King’s The Shining into a Cinematic Masterpiece

Rare 1960s Audio: Stanley Kubrick’s Big Interview with The New Yorker

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow.

“Any problems with the kitchen – you phone me.” Although this might not seem related to the film, it sounds very much like a knowing line of dialogue for the cook. He knows there will be problems, and is offering a lifeline. It’s the opposite of saying something like, “You’re on your own.”

King is a hack with a moderate talent for patented “King” dialogue. Kubrick was a genius who didn’t much care what King called the horror genre. King’s efforts to “remake” The Shining, and the shabby tv movie he oversaw was garbage.

I think this is exactly right. It sounds like Kubrick is trying to compose snippets of screenplay dialogue.