Image by Harry Palmer, via Wikimedia Commons

One reason I’m glad for having had a childhood religious education: it has made me conversant in even some of the most obscure stories and ideas in the Christian Bible, which is everywhere in English literature. Not only was the King James translation formative for early modern English, but stories like that of King David and his son Absalom have furnished material for great works from John Dryden’s dense political allegory “Absalom and Achitophel” to William Faulkner’s dense modernist fable Absalom, Absalom! Then, of course, there’s so much of the work of Blake, Shakespeare, and Milton to account for. Without a fairly solid grounding in Biblical literature, it can be doubly difficult to make headway in a study of the secular variety.

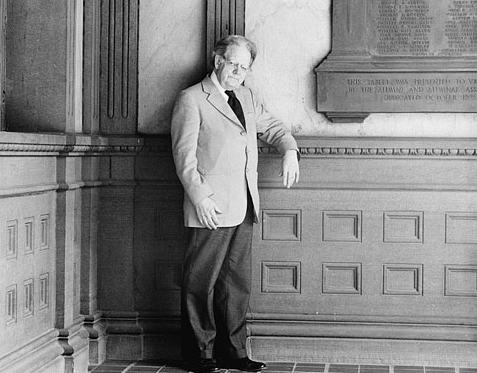

The students of highly regarded Canadian literary critic Northrop Frye found this to be true. As a junior instructor, Frye had difficulty getting his class to understand what was going on in John Milton’s Paradise Lost because so many of the Biblical allusions were lost on them. (It’s a hard enough poem to grasp when you get the references.) “How do you expect to teach Paradise Lost,” said the chair of Frye’s department, “to people who don’t know the difference between a Philistine and a Pharisee?” Responding to this gap in cultural literacy, Frye designed and taught “The Bible and English Literature.” The entire, videotaped course from a 1981 session at the University of Toronto is available online in 25 lectures.

It’s very much a treat to sit in on these lectures. Frye’s work on myth and folktale in English literature is still nearly definitive; his 1957 Anatomy of Criticism, though picked apart many times over through the decades, retains an authoritative place in studies of literary archetypes and rhetoric. Frye’s lectures on the Bible focus on what he sees as its “narrative unity,” due in part to “a number of recurring images: mountain, sheep, river, hill, pasture, bride, bread, wine and so on.” He also spends a good deal of time, at least in his first lecture above, discussing church history, theological and critical conflicts, and the history of various translations. The UToronto site includes full transcripts of each lecture, and the entire course promises to be enlightening for students of literature, of the Bible and church history, or both.

The Bible and English Literature will be added to our list of Free Online Literature Courses and Free Online Religion Courses, part of our larger collection, 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities.

Related Content:

Harvard Presents Two Free Online Courses on the Old Testament

Oxford University Presents the 550-Year-Old Gutenberg Bible in Spectacular, High-Res Detail

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

Thanks for this. It is the internet at its best!

I taught the New Testament as Literature, and would not teach the Old Testament as Literature at the two year college. I fully embrace, to me, very well known work of Northrop Frye, and I appreciate your share. “Off and on the record,” I would just like to say the following: if you try to teach this course at the two year college “arm” yourself with lots of patience. nnnI am not sure how anybody in the USA could easily go about the teaching of the Apocrypha Gospels at the two year college level?! My view on this is the following: if you survive students’ evaluations after teaching of the Apocrypha Gospels, you can walk on water or (if not any) over the Sky! nnnDeliberately, I stayed away of teaching the Old Testament as Literature knowing that I would begin with the Book of Genesis and the three historical editing of the “sacred” text, where God is called by the three different names: Elohim (the Jewish “tribal” or primeordial name for the God), Yahweh (the best known original Jewish name for the Old Testament God), and Adonai (“the Lord,” the name for God that was used during the Davidic Kingdom)–meaning that the Book of Genesis underwent at least the three historical editing of one sacred text, and I know that I would face a great confrontation in the classroom for analyzing this text. I also know I might be wrong; depends where you are, but these are my unique experiences before eight years ago and I hope today’s higher ed. students would be more willing to accept the Bible scholarship, rather than the simplistic “Sunday School” assumptions about the Bible. Any comments?

Scholarship in a few last decades have exceeded Northrop Frye;s interpretations; I suggest Dominic Crossan, Elaine Pagels, and Rodney Stark–each of them different views on Jesus, the New Testament, or transformation of the “cultic & sectarian” Christianity into the world religious movement.