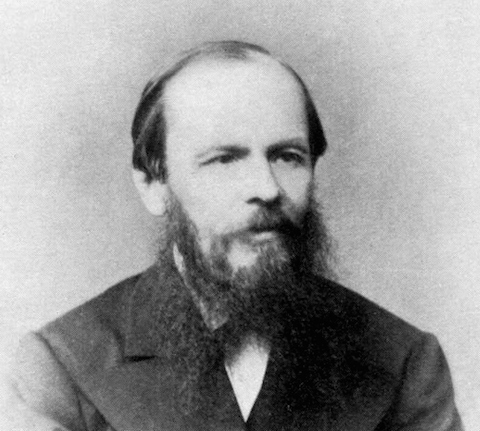

In the pantheon of Great Russian Writers, two heads appear to tower above all others—at least for us English-language readers. Leo Tolstoy, aristocrat-turned-mystic, whose detailed realism feels like a fictionalized documentary of 19th century Russian life; and Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky, the once-condemned-to-death, epileptic former gambler, whose fever-dream novels read like psychological case studies of people barely clinging to the jagged edges of that same society. Both novelists are read with similar reverence and devotion by their fans, and they are often pitted against each other, writes Kevin Hartnett at The Millions, like “Williams vs. DiMaggio and Bird vs. Magic,” even as people who have these kinds arguments acknowledge them both as “irreducibly great.”

I’ve had the Tolstoy vs. Dostoevsky back and forth a time or two, and I have to say I usually give the edge to Dostoevsky. It’s the high-stakes desperation of his characters, the tragic irony of their un-self-awareness, or the gnawing obsession of those who know a little bit too much, about themselves and everyone else. Dostoyevsky has long been described as a psychological novelist. Nietzsche famously called him “the only psychologist from whom I have anything to learn.” Henry Miller’s praise of the writer of particularly Russian forms of misery and trespass is a little more colorful: “Dostoevsky,” he wrote, “is chaos and fecundity. Humanity, with him, is but a vortex in the bubbling maelstrom.”

Perhaps the most succinct statement on the Russian novelist’s work comes from Scottish poet and novelist Edwin Muir, who said, “Dostoyevsky wrote of the unconscious as if it were conscious; that is in reality the reason why his characters seem ‘pathological,’ while they are only visualized more clearly than any other figures in imaginative literature.” Joseph Conrad may have found him “too Russian,” but even with the cultural gulf that separates him from us, and the well over one hundred years of social, political, and technological change, we still read Dostoevsky and see our own inner darkness reflected back at us—our hypocrisies, neuroses, obsessions, terrors, doubts, and even the paranoia and narcissism we think unique to our internet age.

This kind of thing can be unsettling. Although, like Tolstoy, Dostoevsky embraced a fiercely uncompromising Christianity—one more wracked with painful doubt, perhaps, but no less sincere—his willingness to descend into the lowest depths of the human psyche made him seem to Turgenev like “the nastiest Christian I’ve ever met.” I’m not sure if that was meant as a compliment, but it’s perhaps a fitting description of the creator of such expressly vicious characters as Crime and Punishment’s sociopathic Arkady Svidrigailov, Demons’ cruel rapist Nikolai Stavrogin, and The Brothers Karamazov’s psychopathic creep Pavel Smerdyakov (a character so nasty he inspired a Marvel comics villain).

Next to these devils, Dostoevsky places saints: Crime and Punishment’s Sonya, Karamazov brother Alyosha the monk, and holy fool Prince Myshkin in The Idiot. His characters frequently murder and redeem each other, but they also work out existential crises, have lengthy theological arguments, and illustrate the author’s philosophical ideas about faith and its lack. The genius of Dostoevsky lies in his ability to explore such heady abstractions while rarely becoming didactic or turning his characters into puppets. On the contrary—no figures in modern literature seem so alive and three-dimensional as his anguished collection of unforgettable anarchists, aristocrats, poor folks, criminals, flaneurs, and underground men.

Should you have missed out on the pleasure, if it can so be called, of fully immersing yourself in Dostoevsky’s world of fear, belief, and madness—or should you desire to refresh your knowledge of his dense and multifaceted work—you can find all of his major novels and novellas online in a variety of formats. We’ve done you the favor of compiling them below in ebook format. Where possible, we’ve also included audio books too. (Note: they all permanently reside in our Free eBooks and Free Audio Books collections.)

- Poor Folk (1846)

- eBook: Kindle + Other Formats

- The Double (1846)

- eBook: Kindle + Other Formats

- Notes From the Underground (1864)

- eBook: iPad/iPhone — Kindle + Other Formats

- Audio Book: Free MP3

- Crime and Punishment (1866)

- eBook: iPad/iPhone — Kindle + Other Formats — Read Online

- Audio Book: Free iTunes — Free MP3

- “The Dream of a Ridiculous Man” (1877)

- eBook: Read Online

- Audio Book: Free Stream

- The Gambler (1867)

- eBook: iPad/iPhone — Kindle + Other Formats

- Audio Book: Free MP3 Zip File — Free Stream

- The Idiot (1868/69)

- eBook: iPad/iPhone — Kindle + Other Formats

- Audio Book: Free MP3 Zip File — Free Stream

- Demons (also translated as The Possessed and The Devils, 1872)

- eBook: iPad/iPhone — Kindle + Other Formats

- Free Audio Book: Free MP3 Zip File — Free MP3

- The Adolescent (also translated as A Raw Youth, 1875)

- Free eBook: Kindle + Other Formats

- The Brothers Karamazov (1880)

- eBook: iPad/iPhone — Kindle + Other Formats — Read Online

- Audio Book: Free iTunes — Free Stream — Free MP3 Zip File

Find more of Dostoevsky’s work—including his sketches of prison life in Siberia and many of his short stories—at Project Gutenberg. Like his contemporary Charles Dickens, Dostoevsky’s novels were serialized in periodicals, and their plots (and character names) can be winding, convoluted, and difficult to follow. For a comprehensive guide through the life and work of the Russian psychological realist, see Christiaan Stange’s “Dostoevsky Research Station,” an online database with full text of the author’s work and links to artwork, critical essays, bibliographies, quotations, study guides and outlines, and museums and “historically important places.” And for even more resources, see FyodorDostoevsky.com, a huge archive of texts, essays, links, pictures and more. Enjoy!

Related Content:

The Digital Nietzsche: Download Nietzsche’s Major Works as Free eBooks

Watch a Hand-Painted Animation of Dostoevsky’s “The Dream of a Ridiculous Man”

Watch Piotr Dumala’s Wonderful Animations of Literary Works by Kafka and Dostoevsky

The Historic Meeting Between Dickens and Dostoevsky Revealed as a Great Literary Hoax

Crime and Punishment: Free AudioBook and eBook

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Thanks for a great resource! Extremely happy about the audios.