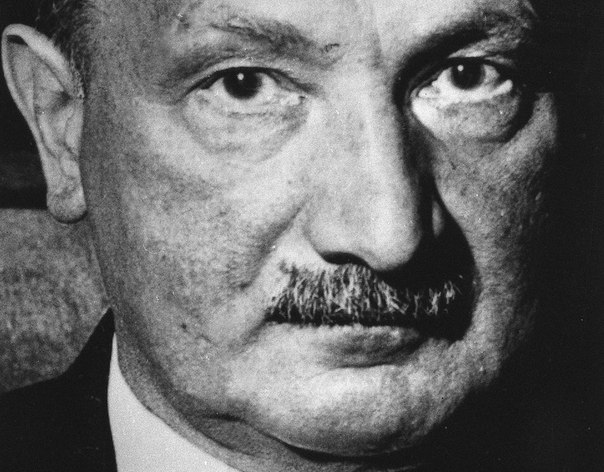

German philosopher Martin Heidegger, widely considered one of the most influential philosophers of the 20th century, was a Nazi, a fact known to most anyone with more than a passing knowledge of the subject. In a New York Review of Books essay, Harvard intellectual historian Peter E. Gordon points out that “the philosopher’s complicity with the Nazis first became a topic of controversy in the pages of Les Temps modernes shortly after the war.” The issue arose again when a former student of Heidegger published “a vigorous denunciation” in 1987. In these cases, and others—like his protégé and onetime lover Hannah Arendt’s defense of her former teacher—the scandal tends to “always end with the same unsurprising discovery that Heidegger was a Nazi.”

What stirs up controversy isn’t Heidegger’s membership in the party, but his motivations. Was he simply a shrewd, if craven, careerist, or a genuinely hateful anti-Semite, or a little from each column? Whatever the explanation, Heideggerians have been able to wall off the philosophy from supposed moral or political lapses in judgment. Arendt did so by claiming that Heidegger, and all of philosophy, was politically naïve. Recalls Adam Kirsch in the Times:

The seal was set on his absolution by Hannah Arendt, in a birthday address broadcast on West German radio. Heidegger’s Nazism, she explained, was an “escapade,” a mistake, which happened only because the thinker naïvely “succumbed to the temptation … to ‘intervene’ in the world of human affairs.” The moral to be drawn from the Heidegger case was that “the thinking ‘I’ is entirely different from the self of consciousness,” so that Heidegger’s thought cannot be contaminated by the actions of the mere man.

The publication of Heidegger’s so-called “black notebooks,” journals that he kept assiduously from 1931–1941, may change all that. They show Heidegger formulating a philosophy of anti-Semitism—using the central categories of his thought—one that operates, as Michel Foucault might say, along “the rules of exclusion.”

In published excerpts of a translation by Richard Polt, an executive member of the Heidegger Circle, Critical Theory shows how much Heidegger turned his own conceptual apparatus against Jews. At one point, he writes:

One of the most secret forms of the gigantic, and perhaps the oldest, is the tenacious skillfulness in calculating, hustling, and intermingling through which the worldlessness of Jewry is grounded.

In this short passage alone, Heidegger invokes lazy stereotypes of Jews as “calculating” and “hustling.” He also, more importantly, describes the Jewish people as “worldless.” As Critical Theory writes, “Being-in-the-world (In-der-Welt-sein) is the basic activity of human existing. To say that the Jews are ‘worldless’… is more than a confused stereotype.” It is Heidegger’s way of casting Jews out of Dasein, his most important category, a word that means something like “being-there” or “presence.” Jews, he writes, are “historyless” and “are not being, but merely ‘calculate with being.’”

Moreover, Heidegger took up the Nazi characterization of Jews as corrupt underminers of society. As representatives of modernity, and its technocratic domination of humanity, the Jews threatened “being” in another way:

What is happening now is the end of the history of the great inception of Occidental humanity, in which inception humanity was called to the guardianship of be-ing, only to transform this calling right away into the pretension to re-present beings in their machinational unessence…

The except goes on at length in this vein, with Jewish “technological machinery” posing a threat to civilization. Perhaps most shockingly, Heidegger attributed Nazi concentration camps to “self-destruction,” completely absolving by omission, and minimizing and excusing, the crimes of his party. An article in Italian newspaper Corriere Della Sera documents Heidegger’s defense of Nazism and his claim in 1942 that “the community of Jews” is “the principle of destruction” and that the camps were only a logical outcome of this principle, the “supreme fulfillment of technology,” “corpse factories.” The real victims, of course, are the Germans, and the Allies are guilty of ”repressing our will for the world.”

Heidegger intended the “black notebooks,” so damning that several scholars of Heidegger fought their publication, to be released after all of his work was published. As with all of the philosopher’s difficult work, the notebooks are often obscure; it is not always clear what he means to say. But major Heidegger scholars have responded in a variety of ways—including resigning a chairship of the Martin Heidegger Society—that suggest the worst. According to Daily Nous, a website about the philosophy profession, when Günter Figal resigned his position in January as chair of the Martin Heidegger Society, he said:

As chairman of a society, which is named after a person, one is in certain way a representative of that person. After reading the Schwarze Hefte [Black Notebooks], especially the antisemitic passages, I do not wish to be such a representative any longer. These statements have not only shocked me, but have turned me around to such an extent that it has become difficult to be a co-representative of this.

Whether or not this new evidence will cause more of his adherents to renounce his work remains to be seen, but the notebooks, writes Peter Gordon, will surely “cast a dark shadow over Heidegger’s legacy.” A very dark shadow.

Related Content:

Martin Heidegger Talks About Language, Being, Marx & Religion in Vintage 1960s Interviews

Martin Heidegger Talks Philosophy with a Buddhist Monk on German Television (1963)

Human, All Too Human: 3‑Part Documentary Profiles Nietzsche, Heidegger & Sartre

Find courses on Heidegger in our collection, 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Pretty irresponsible headlining, to place anti antisemitism at the “heart” of heidegger’s philosophy when in the article itself, examples of his antisemitism all constitute effectively excluding Jews from the core of his philosophy. This isn’t to say these new notes aren’t evidence he was an antisemite; it sounds like he really was. But they’re also just as far from demonstrating how his philosophy itself is rife with Nazi sensibilities as previous publications to that effect have been. If you want to argue that a philosophy is antisemitic, then make it a philosophical argument. The defense I’d give is probably the exact same defense any Heidegger ‘apologist’ might have given were these notebooks never published: If Heidegger meant what he said about the Jews, then he really must not have had them in mind when forming his philosophy of human beings. So it doesn’t obviously follow that his philosophy of human beings is itself antisemitic.

Go ahead and be suspicious of a formulation of humankind drafted up by the kind of person who was willing to cast certain groups of people aside. I know I am. But no self respecting Heidegger fan is going to suddenly think they’ve been suckered into a Nazi philosophy; that’s just ridiculous.

Spot on. I was about to make comment to the exact point. The headline here is nowhere to be found in the article. As well the article itself is entirely misrepresentative, if not crude yellow journalism

Heidegger’s notes on Jews may not be “politically correct” but they are far from showing that Heidegger was a ruthless Nazi thug, that would enjoy eradicating all Jews. He maybe didn’t like Jews, that doesn’t mean he would prefer them dead. On the contrary, he referred to Nazis as “murderers” in private conversations. His notes are “obscure” because everybody accusing Heidegger of being a Nazi has no comprehension of his philosophy. He was in the Nazi party from 1933 to 1934, when its leader’s intentions were not as clear, and I’m sure he would have never accepted to exterminate an entire human race. Criticizing Jews does not make you an anti-Semite, inasmuch as criticizing French or German people does not imply that you wish to exterminate them.

As long as he didn’t call for, or participate in, total murder, who cares? Why goyim bow to their “masters” is beyond me. No religion or religious group deserves the kind of protection given to Jews. Can’t say a single thing in criticism of Jews for fear of being labelled a … ? No way. My question is this: what is it called when Jews openly spout hatred for, say, Muslims?

Nowadays we trend to judge artist, philosophers, writes, scientists like they were politicians.

This is wrong.

You can ask politicians for self-consistency between their ideas and their actions, you can’t do the same for other categories of people, including philosophers.

Philosophers as well as scientists,artists, musicians, writers, should never been judged based on their actions, they are not politicians. You have to look at the value of their work and how much is their influence to the matter they dedicated their lives to ‚not referring to their actions. They don’t spend their lives to persuade you, like politicians do — they just dedicated their lives to their work, which is a different story

He based the notion of being on our ways of doing things as they emerge within a culture or tradition. Arguably it included the ways of doing things in Germany in the 1920s and 30s; to be a human was to be a nazi.

JK,

Tell that to these people. It’s a fairly long, and certainly incomplete list, of people who managed to think otherwise.

Dan

To be a Nazi was a way of being human, rather. I think it’s a fairly common and reasonable criticism of Heidegger that his philosophy isn’t a good jumping off point for morally condemning the Holocaust. I think Habermas said something about this but I may be wrong. As far as I’m concerned, this isn’t that interesting. I couldn’t tell if you were trying to twist Heidegger’s thing into a promotion of the Nazi way of life, but if you were I think it’s more accurate to say his philosophy constitutes no more than a kind of vacuous defense of it, as simply being one locus of human practices among others.

@Dan: so, obviously his notion of ‘being’ was absurd.

@Simon: sure, nazism was one of many human practices. The real problem, however, is that he based ‘being’ on human practices. But being human, for instance, by virtue of nihilating humans, as in genocide, is absurd. Like his obfuscatory interpretation of nothing as something positive. Bitter examples of philosophy gone very wrong.

I was disappointed to see this headline and too-simplistic article on a website that I continually check for updates and information. For a more even handed reflection, see: http://notphilosophy.com/framing-heidegger-technology-and-the-notebooks/

replying to Simon Benarroch:

“If Heidegger meant what he said about the Jews, then he really must not have had them in mind when forming his philosophy of human beings. So it doesn’t obviously follow that his philosophy of human beings is itself antisemitic.”

A philosophy of human beings that excludes Jewish people isn’t obviously anti-Semitic? Really?

I fear I must be misunderstanding you, or whether that is intended to be a serious argument.