No profile of Haruki Murakami, the most globally popular novelist alive, fails to refer to the high number of languages (as of this writing, the count has reached 50) in which his 14 Japanese-language novels have appeared in translation. But outside Japan, monoglot Murakamists (especially readers of only English) have a problem: they still can’t read a wealth of Murakami’s other, non-novelistic writing, including the full-length, two-volume version of Underground, his study of the 1995 Tokyo sarin gas attack; his Portrait in Jazz books on his favorite music; and most of his many essays and movie reviews.

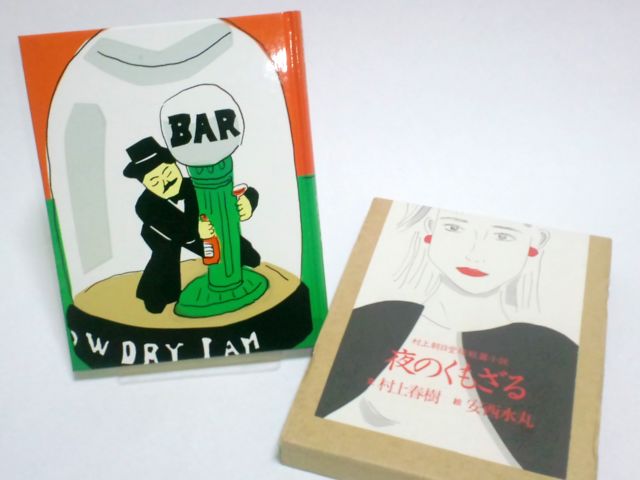

Even some of Murakami’s fiction has remained more or less off-limits to global readers. I discovered this when I came across a collection of his I’d never even heard of while book-shopping in Seoul. Realizing that of course more Murakami material would find its way into Korean, a grammatically similar language to Japanese, than English, I set about checking every bookstore in the city I knew for other unknown volumes. One book of short stories, titled in Korean 밤의 원숭이 (Spider Monkey of the Night), particularly delighted me with its strange and extremely brief tales, each accompanied by charming illustrations.

But where did these stories, with their titles like “Hotel Lobby Oysters,” “Julio Iglesias,” and “Takayama Noriko and My Libido,” come from? They came, as Neojaponisme’s post on them explains, from the world of advertising, and specifically from a company called “Onward,” which marketed the American Ivy League fashion label J. Press in Japan:

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Onward spent massive sums on advertising J. Press in the print media. The classic ad format, often seen on the back cover of lifestyle magazine Popeye, showed a Japanese or American man telling a colorful story about their favorite trad clothing item. In 1985, as Japanese pop culture went in more avant-garde directions, Onward came up with a new idea — asking up-and-coming novelist Murakami Haruki to write a very short story inside each month’s advertisement for magazines Popeye, Box, and Men’s Club.

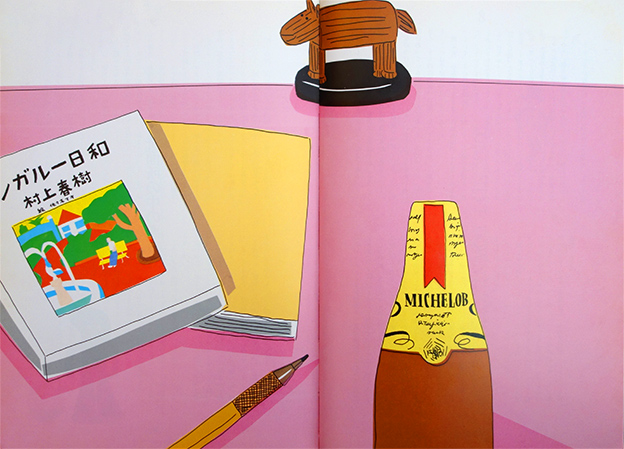

“So once a month from April 1985 to February 1987, Murakami wrote a ‘short short’ (短い短編), which was set on its own page with an illustration by famed artist Anzai Mizumaru at the top and a small J. Press logo in the lower left corner.” During that time, out came Murakami’s hit novel Norwegian Wood, which rocketed him to a level of fame that effectively put him in exile from his homeland. But the advertorial short-short form still appealed to him, and in 1993 he got famous penmaker Parker to sponsor 24 new ones.

To give you a flavor of all this, below is one of the English-language translations floating around of “Hotel Lobby Oysters,” Murakami’s first J. Press story. (You can also read “Miss Noriko Takayama and My Libido,” another J. Press story here):

At the time I was sitting on the hotel lobby sofa and vaguely thinking about oysters. Not lemon soufflé, not pencil sharpeners – oysters. I don’t know why. I just suddenly realized that I was thinking about oysters.

The oysters I was thinking about on the hotel lobby sofa were different from oysters thought about anywhere else. They were shaped differently, they smelled differently, and their color was different, too. They weren’t oysters harvested in some cove. They were pure oysters harvested in a hotel lobby.

After thinking about oysters for a while, I went to the sink to wash my face, then retied my tie and returned to the sofa. When I got back, the oysters had already disappeared from inside my head. Again, I don’t know why. Maybe it was because I washed my faced or because I retied my tie. Or maybe the hotel oyster season is extremely short.

When the girl came 17 minutes after our appointed time, I told her about the hotel lobby oysters. The image was so distinct I felt like I had to tell someone about them.

“You want to eat oysters?” she asked.

“No, these oysters, they were purely oysters as a concept, unrelated to my appetite,” I explained. “The oysters came into being as the very essence of oys—“

“But you do want to eat some, right?” she said.

When she mentioned it and I settled down to think about it, I certainly had developed an incredible desire to eat oysters. We went to the hotel restaurant and ate 25 oysters while drinking wine. Sometimes I think my appetite originates from a really strange place.

And, for Parker, Murakami wrote, “Spider Monkey of the Night”:

I was sitting at my desk at 2:00 in the morning and writing. I pushed my window open and a spider monkey came in.

“Oh, hey, who are you?” I asked.

“Oh, hey, who are you,” the spider monkey said.

“Don’t copy me,” I said.

“Don’t copy me,” the monkey said.

“Don’t copy me,” I copied him.

“Don’t copy me,” he copied me in italics.

Man, this is really annoying, I thought. If I get caught up with this copycat-crazed night monkey, who knows when this will end. I’ll just have to trip him up somewhere. I had a job that I had to finish by morning, and I couldn’t very well keep doing this all night.

“Heppoku rakurashi manga totemuya, kurini kamasu tokimi wakoru, pacopaco,” I said quickly.

“Heppoku rakurashi manga totemuya, kurini kamasu tokimi wakoru, pacopaco,” the spider monkey said.

Since I had said something completely random, I couldn’t actually tell if the monkey had copied me correctly or not. Well, that was pointless.

“Leave me alone,” I said.

“Leave me alone,” the monkey said.

“You got it wrong, I didn’t say it in italics that time.”

“You got it wrong, I didn’t say it in ītalics that time.”

“I didn’t put a macron over the i.”

“I didn’t put a macron over the eye.”

I sighed. No matter what I said, the spider monkey wouldn’t understand. I decided to not say anything and just keep doing my work. Still, when I pressed a key on my word processor, the monkey silently pressed the copy key. Click. Still, when I pressed a key on my word processor, the monkey silently pressed the copy key. Click. Leave me alone. Leave me alone.

via Neojaponisme

Related Content:

Read 3 Stories from Haruki Murakami’s Short Story Collection Published in Japan Last Year

Read 6 Stories By Haruki Murakami Free Online

Haruki Murakami Lists the Three Essential Qualities For All Serious Novelists (And Runners)

Haruki Murakami’s Passion for Jazz: Discover the Novelist’s Jazz Playlist, Jazz Essay & Jazz Bar

Colin Marshall writes on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

You’re quite right about Murakami’s short fiction, but incredibly wrong about your very first point- Underground. This is and has been available in English since 2001. A very quick search of Amazon would reveal that to you.

It’s not the full-length, two-volume version though. A quick read of the article would revel that to you.