A rudimentary difference between fiction narratives and documentary film is supposed to be that one is created out of the imagination, and the other is a recorded document of real events. Yet if we go right back to the very first feature length documentary, Robert J. Flaherty’s Nanook of the North, we see that the line between fact and fiction was just as wobbly then as now.

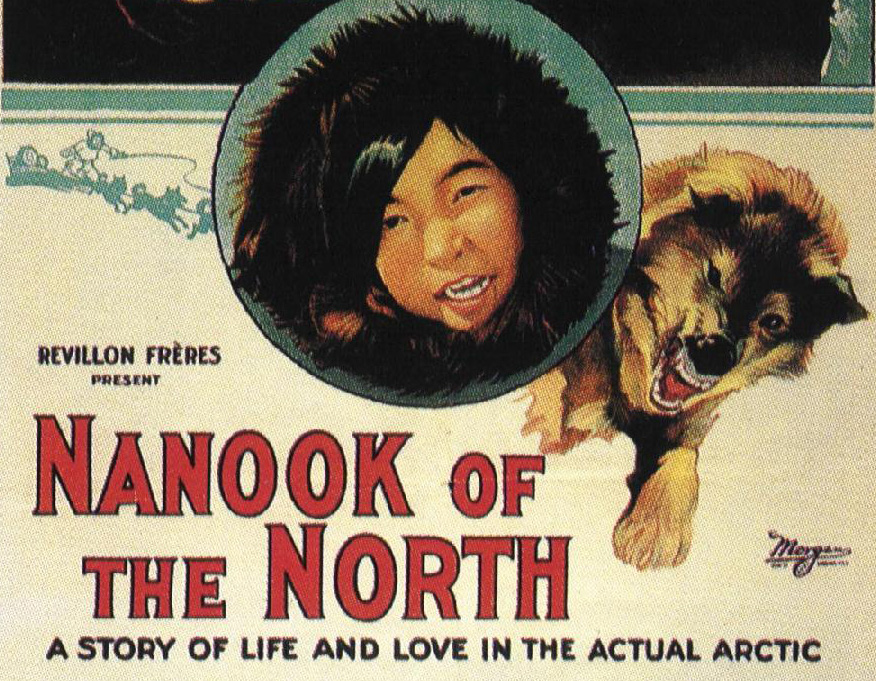

A popular success when it was released in 1922, Nanook brought its heroic title character to an audience who knew nothing about the Native tribes of the north. The film shows a way of life that was disappearing as Flaherty, originally an explorer and prospector, began to document it. We see the hardy Inuit Nanook hunting with spears, pulling up to a trading station in a kayak and trading with the white owner. We see his wife and kids, the family building an igloo and bedding down for the night. The film emphasizes as much his self-reliance as it does Nanook’s naivety. And it fully cemented the idea of the Eskimo in popular culture. Nanook became a name as synonymous with the Inuit as Pierre is to the French. Frank Zappa even wrote a song suite about Nanook.

Flaherty was not trained in film, and learned what he could quickly about photography when he decided to shoot footage up north while working for the Canadian Pacific Railway. He accidentally destroyed all of his original footage when he dropped a cigarette on the flammable nitrite film and set about raising money for a reshoot. Without precedent, Flaherty rethought his doc into what we now recognize as classic form: Instead of trying to capture the culture, he chose one man as his main character, an entry into an unknown world.

And in those reshoots we find the line between fiction and fact blurred. Nanook’s real name was Allakariallak, and though he was a hunter, he and his tribe had long ditched the spear for the much more effective gun. Flaherty wanted to represent Inuit life before the European influence, and Allakariallak played along, not just hunting with his spear, but pretending at the trade outpost not to recognize a gramophone.

The scenes inside the igloo were staged for good reason: the camera was too big and the lighting needed would have melted the walls. So Allakariallak and the crew built a cutaway igloo where the family could pretend to bed down for the night. (Oh, and the two women we see were actually Flaherty’s common law wives.)

Flaherty’s legacy was in combining ethnography, travelogue, and showing how people live and work, none of which had been done before in film. Flaherty continued to make documentaries into 1950, including Man of Aran (about life on the Irish isle of the same name) and Tabu, a Polynesian island tale directed by F.W. Murnau, best known for Nosferatu. But none had the impact of this film. When the Library of Congress first started listing films in 1989 for preservation, specifying ones that were “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant,” Nanook was in the first selection of 25.

The idea of building a living habitat in order to control the action still happens in nature documentaries, and humans readily playing a version of themselves to tell a certain kind of narrative is the basis of all reality TV. Flaherty bent boring truth to get to a different, “essential” truth. Is it better that we believe that Nanook died out on the ice, a victim of the harsh reality of survival on the ice, or to know that he actually died at home from tuberculosis? The qualities that caused controversy upon Nanook’s release aren’t the opposite of documentary, they *are* documentary.

Related Content:

The 10 Greatest Documentaries of All Time According to 340 Filmmakers and Critics

Watch Luis Buñuel’s Surreal Travel Documentary A Land Without Bread (1933)

Watch Dziga Vertov’s Unsettling Soviet Toys: The First Soviet Animated Movie Ever (1924)

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the FunkZone Podcast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.

I like to think of Edward Curtis’s “In the Land of the Head Hunters” (also called “In the Land of the War Canoes”) as the first documentary.

The Doors famously incorporated this film into their video for the song ‘Wild Child’, and they did it very well!

This is incredible footage. Never saw this before. We know almost nothing about the way of life these eskimo´s were having. Brilliant video, thanks!