If you’ve ever had difficulty pronouncing the word Yoknapatawpha—the fictional Mississippi county where William Faulkner set his best-known fiction—you can take instruction from the author himself. During his time as writer-in-residence at the University of Virginia, Faulkner gave students a brief lesson on his pronunciation of the Chickasaw-derived word, which, as he says, sounds like it’s spelled.

If you’ve ever had difficulty getting around in Yoknapatawpha—getting the lay of the land, as it were—Faulkner has stepped in again to help his readers. He drew several maps of varying levels of detail that show Yoknapatawpha, its county seat of Jefferson in the center, and various key characters’ plantations, crossroads, camps, stores, houses, etc. from the fifteen novels and story cycles set in the author’s native Mississippi.

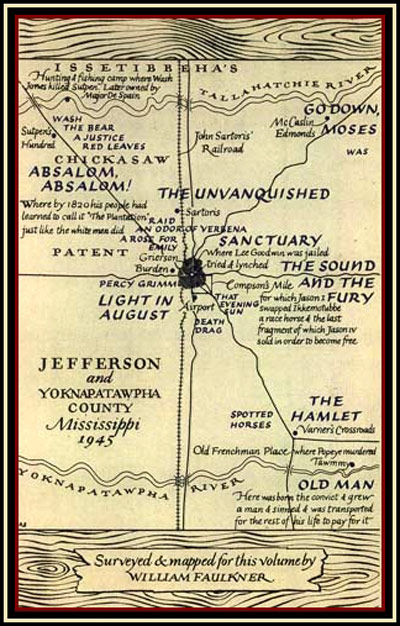

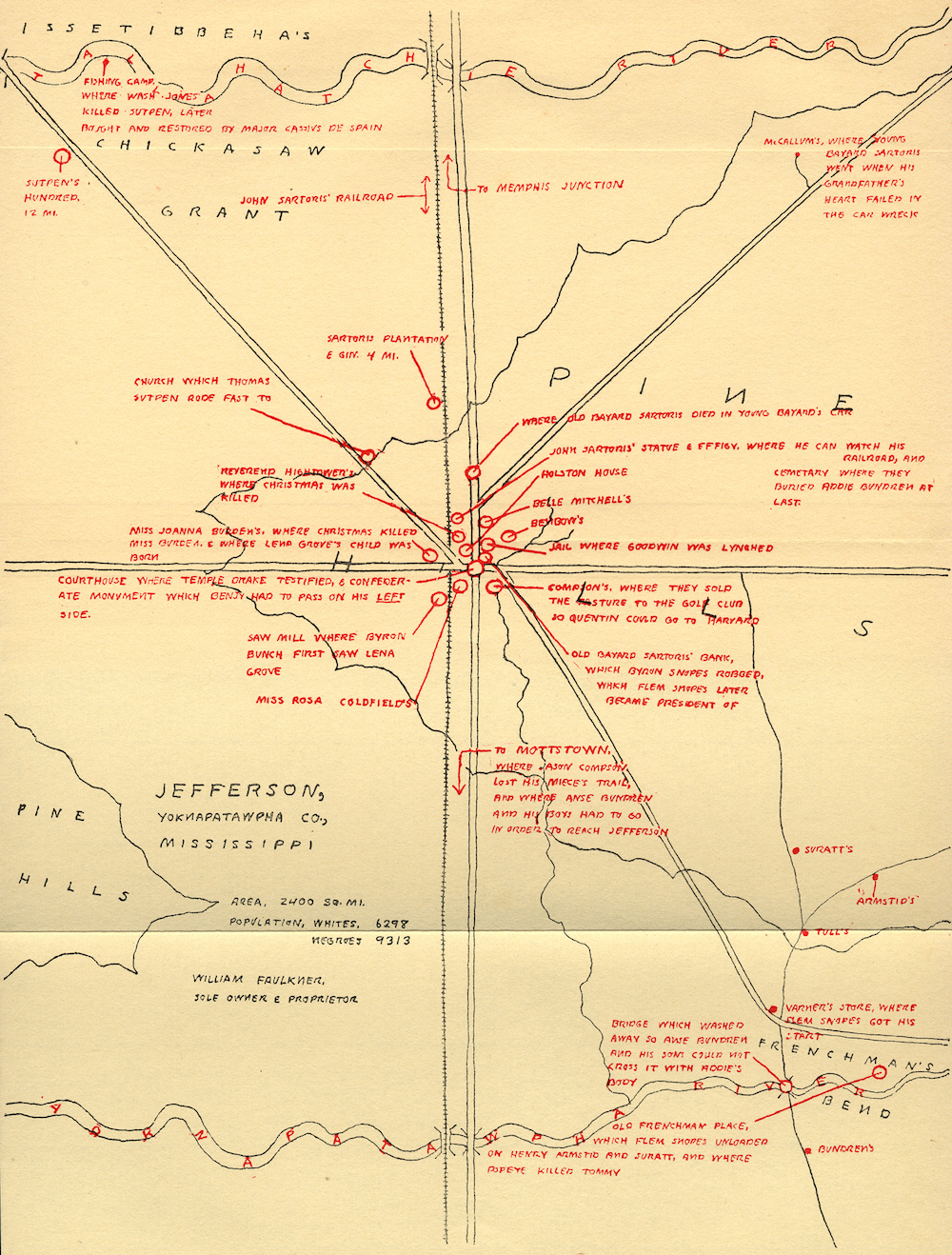

Perhaps the most reproduced of Faulkner’s maps, above, comes from 1946’s The Portable Faulkner and was drawn by the author at the request of editor Malcolm Cowley. We see named on the map the locations of settings in The Unvanquished, Sanctuary, The Sound and the Fury, The Hamlet, Go Down, Moses, Light in August, and the stories “A Rose for Emily” and “Old Man,” among others. This map, dated 1945, had an important predecessor, however: the map below, the final page in Faulkner’s epic tragedy Absalom, Absalom! Most readers of that novel, myself included, have thought of Quentin Compson’s deeply conflicted, repeated assertions that he doesn’t hate the South as the novel’s conclusion. It’s a passionate speech as memorable, and as final, as Molly Bloom’s silent “Yes” at the end of Joyce’s Ulysses. Not so, writes Faulkner scholar Robert Hamblin, the novel actually ends after Quentin, and after the appendix’s chronology and genealogy; the novel truly ends with the map.

What Hamblin wants us to acknowledge is that the map creates more ambiguity than it resolves. The map, he says “is more than a graphic representation of an actual place”—or in this case, a fictional place based on an actual place—“it is simultaneously a metaphor.” While it further attempts to situate the novel in history, giving Yoknapatawpha the tangibility of Thomas Hardy’s fictional Wessex or Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, the map also elevates the county to a mythic dimension, like “Bullfinch’s maps depicting the settings of the Greek and Roman myths and the wanderings of Ulysses, Sir Thomas More’s map of Utopia, Jonathan Swift’s maps of the travels of Lemuel Gulliver.”

The Portable Faulkner map at the top of the post appears “in a style unlike Faulkner’s” and was “much reduced for publication in first and subsequent printings,” A Companion to William Faulkner tells us. The Absalom map, on the other hand, appeared in a first, limited-edition of the novel in 1936, hand-drawn and lettered in red and black ink, a color-coding feature common to “Faulkner’s many hand-made books.” Click the image, then click it again to zoom in and read the details. You’ll notice a number of odd things. For one, Faulkner gives equal attention to naming locations and describing events that occurred in other Yoknapatawpha novels, mainly murders, deaths, and various crimes and hardships. For another, his neat capital lettering reproduces the letter “N” backwards several times, but just as many times he writes it normally, occasionally doing both in the same word or name—a stylistic quirk that is not reproduced in The Portable Faulkner map.

Finally, in contrast to the map at the top, which Faulkner gives his name to as one who “surveyed & mapped” the territory,” in the Absalom map, he lists himself—beneath the town and county names, square mileage, and population count by race—as “sole owner & proprietor.” Against Alfred Korzybski’s famous dictum, Tokizane Sanae insists that at least when it comes to literary maps, “Map is Territory… proof of newly conquered ownership of a land”—the territory of a deed. Suitably, Faulkner ends a novel obsessed with ownership and property with a statement of ownership and property—over his entire fictional universe. In an ironic exaggeration of the power of surveyors, cartographers, architects, and their landowning employers, the map “spatializes and visualizes the concept of a mythical soil and the power of this God.” In that sense, it forces us to view all of the Mississippi novels not as historical fiction, but as episodes in a great religious mythology, with the same depth and resonance as ancient scripture or political allegory.

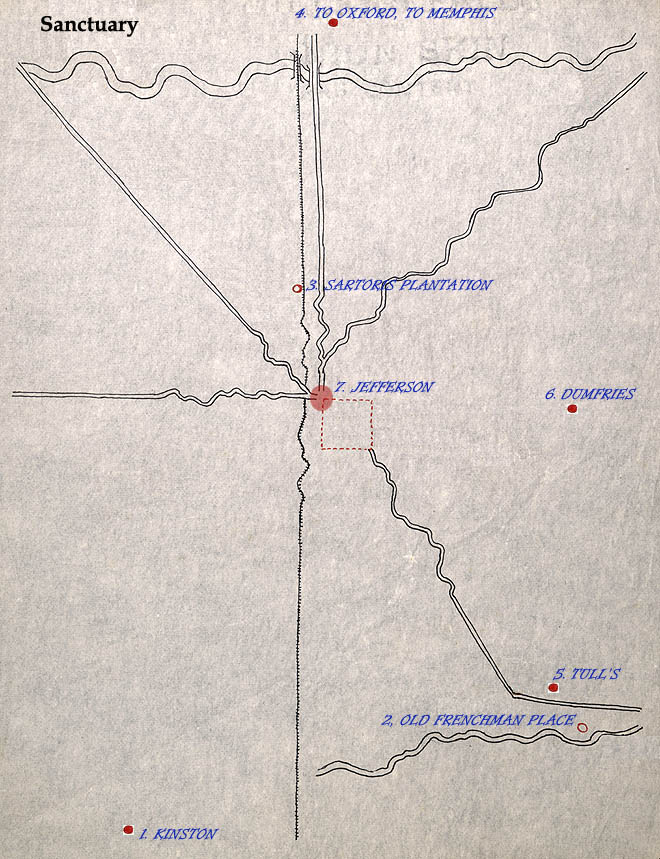

If we wish to see Faulkner’s map this way—a zoom out into an aerial shot at the end of an epic picture—then we’re unlikely to find it of much use as a guide to the plain-faced logistics of his fiction. It’s unclear to me that Faulkner intended it that way, as much as it’s unclear that Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot’s footnotes to The Waste Land serve any purpose except to distract and confuse readers. But of course readers have been using those footnotes, and Faulkner’s map, as guidelines to their respective texts for decades anyway, noting inconsistencies and finding meaningful correspondences where they can. One interesting example of such a use of Faulkner’s mapmaking comes to us from the site of a comprehensive University of Virginia Faulkner course that covers a bulk of the Yoknapatawpha books. The project, “Mapping Faulkner,” begins with a considerably sparser Yoknapatawpha map, one probably made “late in his life” and which “seems unfinished,” lacking most of the place names and descriptions, and certainly the assertive signature. With overlaid blue lettering, the site does what the Absalom map does not—gives each novel, or 9 of them anyway, its own map, with discrete boundaries between events, characters, and time periods.

If Faulkner wanted us to see the books as manifestations of a singular consciousness, all radiating from a single source of wisdom, this project isolates each novel, and its themes. In the map of Sanctuary, above, only locations from that novel appear. On the page itself, a click on the circular markings under each locale brings up a window with annotations and page references. The apparatus might at first appear to be a useful guide through the notoriously difficult novels, provided Faulkner meant the locations to actually correspond to the text in this way. But what are we to do with this visual information? Lacking any legend, we can’t use the map to judge scale and distance. And by removing all of the other events occurring in the vicinity in the span of around a hundred years or so, the maps denude the novels of their greater context, the purpose to which their “owner & proprietor” devoted them at the end of Absalom, Absalom! Faulkner’s maps, as works of art in their own right, extend “the tragic view of life and history that the Sutpen narrative has already conveyed” in Absalom, Absalom!, writes Hamblin: “Through the handwritten entries that Faulkner made,” in that map, the most complete drawn in the author’s own hand, “the landscape of Yoknapatawpha is presented primarily as a setting for grief, villainy, and death.”

View more maps by Faulkner here.

Related Content:

The Art of William Faulkner: Drawings from 1916–1925

Revel in The William Faulkner Audio Archive on the Author’s 118th Birthday

William Faulkner Resigns From His Post Office Job With a Spectacular Letter (1924)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Until now I didn’t know your website: it is because I have put “likes” on William Faukner’s articles and curiosities that I’ve come to get to know you.

Thank you for your interesting, enlightening website!

Ages ago, when I was a university student,I 2met” W.Faulkner’s books and it was ove at first sight. Then I wrote my final thesis on “As I lay dying”… Faulkner is and will always be my first love!

This is really helpful. Thank you so much for posting the different maps all in one place and discussing them in a way that’s so helpful. I found a map of the county that is very detailed and I can’t tell where it came from originally but the picture of it looks cropped (and slanted..) and some of the details/info is cut off. Can you tell me where I might find a better copy of this map and what it’s origins might be? I don’t want to post a direct link incase that’s frowned on so please replace the word “dot” with a . It’s at http://ummuseumeducation blogspot.com/2013/05/currently-um-museum-has-breathtaking.html Thank you very much.