After his radical conversion to Christian anarchism, Leo Tolstoy adopted a deeply contrarian attitude. The vehemence of his attacks on the class and traditions that produced him were so vigorous that certain critics, now mostly obsolete, might call his struggle Oedipal. Tolstoy thoroughly opposed the patriarchal institutions he saw oppressing working people and constraining the spiritual life he embraced. He championed revolution, “a change of a people’s relation towards Power,” as he wrote in a 1907 pamphlet, “The Meaning of the Russian Revolution”: “Such a change is now taking place in Russia, and we, the whole Russian people, are accomplishing it.”

In that “we,” Tolstoy aligns himself with the Russian peasantry, as he does in other pamphlets like the 1909-10 journal, “Three Days in the Village.” These essays and others of the period rough out a political philosophy and cultural criticism, often aimed at affirming the ruddy moral health of the peasantry and pointing up the decadence of the aristocracy and its institutions. In keeping with the theme, one of Tolstoy’s pamphlets, a 1906 essay on Shakespeare, takes on that most hallowed of literary forefathers and expresses “my own long-established opinion about the works of Shakespeare, in direct opposition, as it is, to that established in all the whole European world.”

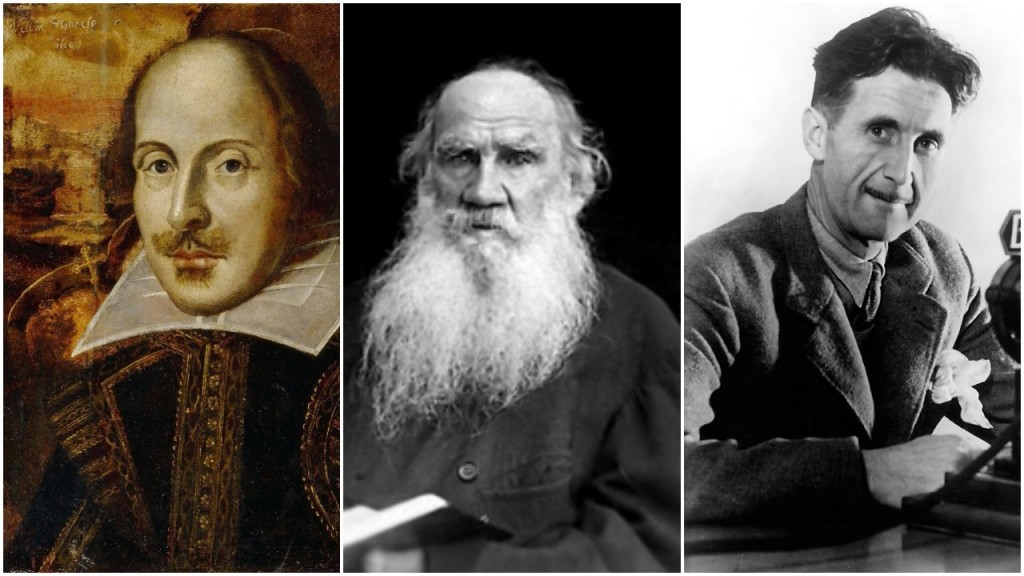

After a lengthy analysis of King Lear, Tolstoy concludes that the English playwright’s “works do not satisfy the demands of all art, and, besides this, their tendency is of the lowest and most immoral.” But how had all of the Western world been lead to universally admire Shakespeare, a writer who “might have been whatever you like, but he was not an artist”? Through what Tolstoy calls an “epidemic suggestion” spread primarily by German professors in the late 18th century. In 21st-century parlance, we might say the Shakespeare-as-genius meme went viral.

Tolstoy also characterizes Shakespeare-veneration as a harmful cultural vaccination administered to everyone without their consent: “free-minded individuals, not inoculated with Shakespeare-worship, are no longer to be found in our Christian society,” he writes, “Every man of our society and time, from the first period of his conscious life, has been inoculated with the idea that Shakespeare is a genius, a poet, and a dramatist, and that all his writings are the height of perfection.”

In truth, Tolstoy proclaims, the venerated Bard is “an insignificant, inartistic writer…. The sooner people free themselves from the false glorification of Shakespeare, the better it will be.”

I have felt with… firm, indubitable conviction that the unquestionable glory of a great genius which Shakespeare enjoys, and which compels writers of our time to imitate him and readers and spectators to discover in him non-existent merits — thereby distorting their aesthetic and ethical understanding — is a great evil, as is every untruth.

What could have possessed the writer of such celebrated classics as War and Peace and Anna Karenina (find them in our collection of Free eBooks) to so forcefully repudiate the author of King Lear? Forty years later, George Orwell responded to Tolstoy’s attack in an essay titled “Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool” (1947). His answer? Tolstoy’s objections “to the raggedness of Shakespeare’s plays, the irrelevancies, the incredible plots, the exaggerated language,” are at bottom an objection to Shakespeare’s earthy humanism, his “exuberance,” or—to use another psychoanalytic term—his juissance. “Tolstoy,” writes Orwell, “is not simply trying to rob others of a pleasure he does not share. He is doing that, but his quarrel with Shakespeare goes further. It is the quarrel between the religious and the humanist attitudes towards life.”

Orwell grants that “much rubbish has been written about Shakespeare as a philosopher, as a psychologist, as a ‘great moral teacher’, and what-not.” In reality, he says, the playwright, was not “a systematic thinker,” nor do we even know “how much of the work attributed to him was actually written by him.” Nonetheless, he goes on to show the ways in which Tolstoy’s critical summary of Lear relies on highly biased language and misleading methods. Furthermore, Tolstoy “hardly deals with Shakespeare as a poet.”

But why, Orwell asks, does Tolstoy pick on Lear, specifically? Because of the character’s strong resemblance to Tolstoy himself. “Lear renounces his throne,” he writes, “but expects everyone to continue treating him as a king.”

But is it not also curiously similar to the history of Tolstoy himself? There is a general resemblance which one can hardly avoid seeing, because the most impressive event in Tolstoy’s life, as in Lear’s, was a huge and gratuitous act of renunciation. In his old age, he renounced his estate, his title and his copyrights, and made an attempt — a sincere attempt, though it was not successful — to escape from his privileged position and live the life of a peasant. But the deeper resemblance lies in the fact that Tolstoy, like Lear, acted on mistaken motives and failed to get the results he had hoped for. According to Tolstoy, the aim of every human being is happiness, and happiness can only be attained by doing the will of God. But doing the will of God means casting off all earthly pleasures and ambitions, and living only for others. Ultimately, therefore, Tolstoy renounced the world under the expectation that this would make him happier. But if there is one thing certain about his later years, it is that he was NOT happy.

Though Orwell doubts the Russian novelist was aware of it—or would have admitted it had anyone said so—his essay on Shakespeare seems to take the lessons of Lear quite personally. “Tolstoy was not a saint,” Orwell writes, “but he tried very hard to make himself into a saint, and the standards he applied to literature were other-worldly ones.” Thus, he could not stomach Shakespeare’s “considerable streak of worldliness” and “ordinary, belly-to-earth selfishness,” in part because he could not stomach these qualities in himself. It’s a common, sweeping, charge, that a critic’s judgment reflects much of their personal preoccupations and little of the work itself. Such psychologizing of a writer’s motives is often uncalled-for. But in this case, Orwell seems to have laid bare a genuinely personal psychological struggle in Tolstoy’s essay on Shakespeare, and perhaps put his finger on a source of Tolstoy’s violent reaction to King Lear in particular, which “points out the results of practicing self-denial for selfish reasons.”

Orwell draws an even larger point from the philosophical differences Tolstoy has with Shakespeare: “Ultimately it is the Christian attitude which is self-interested and hedonistic,” he writes, “since the aim is always to get away from the painful struggle of earthly life and find eternal peace in some kind of Heaven or Nirvana…. Often there is a seeming truce between the humanist and the religious believer, but in fact their attitudes cannot be reconciled: one must choose between this world and the next.” On this last point, no doubt, Tolstoy and Orwell would agree. In Orwell’s analysis, Tolstoy’s polemic against Shakespeare’s humanism further “sharpens the contradictions,” we might say, between the two attitudes, and between his own former humanism and the fervent, if unhappy, religiosity of his later years.

Related Content:

Leo Tolstoy’s 17 “Rules of Life:” Wake at 5am, Help the Poor, & Only Two Brothel Visits Per Month

Leo Tolstoy’s Masochistic Diary: I Am Guilty of “Sloth,” “Cowardice” & “Sissiness” (1851)

Download 55 Free Online Literature Courses: From Dante and Milton to Kerouac and Tolkien

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

I remember, according to his theory of art, Tolstoy thought Charles Dickens was art and Shakespeare was not. Accordingly Victor Hugo was, Molier and Goethe were not. Even ignorant peasant oldman should’ve been absorbed to feel humanitarian. Which I could not agree. It was my freshman summer vacation days that I read his whole theories in 1974.

In the end of all this blather, it’s what his words mean to the reader or what they mean to the ticket holder.

Poor Tolstoi. He was crazy. Shakespeare, Rafaelo Sanzio, Beethoven and others genius

If Tolstoy attacked Goethe and Moliere then it seems pretty clear he objected to humanist authors who imitated pagan Greece and Rome.

Shakespeare was the Steven King of his time. The establishment couldn’t stand it!

Just read Tolstoy.

I don’t think Tolstoi read Shakespeare, and if he read Shakespeare he surely didn’t understand him, and in what language did he read Shakespeare, I tried to read him in Freanch it wasn’t the same as in English. Of course we shouldn’t judge an old communist for being a genuise but also a shmock…

To call shakespear “insignificant and inartistic writer” does simply mean a poor judgement of his works. As shakespears’ almost all works are replete with shimmering artestry,but i get confused to ponder over what the parameters Tolystoi took to judge the works of shakespear.

Tolstoi was a communist?! You are an idiot, he died in 1910, in Russian Empire. Try to learn a little bit history before terrible communists will come to conquer your country

From what I remember, Tolstoy believed art’s primary purpose to be a moral one, to reveal injustice and offer spiritual guidance. Hence, to Tolstoy, Hugo was art and Shakespeare was not. It’s a ridiculous criterium for art, in my view, but luckily we don’t have to share it, and can simply be enriched by Tolstoy’s fiction, which is as close in richness and depth to Shakespeare’s plays and poems as any writer I can think of.

how truly ironic

Sami sorry to have made so angry, but I read Tolstoi’s complete works and I think that he was one of the best writers in the world, but as they wrote in this article: He championed revolution, “a change of a people’s relation towards Power,” as he wrote in a 1907 pamphlet, “The Meaning of the Russian Revolution”: “Such a change is now taking place in Russia, and we, the whole Russian people, are accomplishing it.” What do you think does that mean?

I really don’t know what my country has to do with this!!!

Tolstoy is a master storyteller. S. deals not in story but in the humming swarm of personalities fighting to out-exist each other.

Tolstoy did read Shakespeare’s plays. He specifically lists King Lear,” “Romeo and Juliet,” “Hamlet,” “Macbeth,” “Henrys,” “Troilus and Cressida,” the “Tempest,” and “Cymbeline.” He read them in Russian, German, and English. He read them several times throughout his life and made a very strong attempt to understand them. Say what you will, but you can’t say that he was ignorant of the material.

Exactly.

Also, it seems nobody reads Tolstoy’s criticism piece properly.

The idea that Tolstoy is criticising Shakespeare on religious or moral grounds misses what the Russian says right at the start:

“For a long time I could not believe in myself, and during fifty years, in order to test myself, I several times recommenced reading Shakespeare in every possible form, in Russian, in English, in German and in Schlegel’s translation, as I was advised.”

Fifty years. That means he was repelled by Shakespeare even before he had published War & Peace, long before his Great Change of Heart in literature.

To dismiss this as Tolstoy’s moralism and to assume he disliked Shakespeare’s humanism is anachronistic.

The Russian held this opinion when his own work was an exercise in humanism and manysided depiction of life and character.

Even if we do not wish to agree with Tolstoy’s condemnation of Shakespeare, I think we have to recognise that probably there is a perspective, and a humanist one at that, which finds some aspect of Shakespeare seriously flawed.

Not just flawed.

Seriously empty.

What that aspect is and why most literary minds are blind to it is a much worthier subject for a rejoinder than what Orwell had to offer.

Tolstoy of course read Shakespeare in English, Moliere and Hugo in French, and Goethe in German. He was, like most old aristocrats, polyglot. His knowledge of French and English were impeccable.